The maternal death rate is 60 percent higher in rural areas than central parts of metropolitan areas. A bill introduced by a member of Congress from New Mexico seeks to close the gap.

As pregnancy-related deaths in rural areas climb, federal lawmakers hope to reverse the trend with legislation that will attract more healthcare providers to rural areas and identify the causes of pregnancy-related deaths.

In September, U.S. Representative Xochitl Torres Small, D-New Mexico, introduced HB 4243, the Rural Maternal and Obstetric Modernization of Services Act (the Rural MOMS Act). The bill would add incentives to attract healthcare providers, fund equipment purchases and support data collection on maternal health and morbidity in rural areas.

The U.S. ranks as one of the worst developed nations for maternal mortality, with more pregnancy-related deaths than Saudi Arabia and Kazakhstan. Rural parts of the U.S. have 60 percent higher mortality rates, according to 2015 data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The report says the mortality rate in large central metropolitan areas was 18.2 per 100,000 live births, compared to 29.4 per 100,000 live births in the most rural areas.

In May, Seema Verna, the director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said in her statement to the National Rural Health Association Conference in Atlanta that maternal health was one of her department’s top priorities.

“Maternal health is a growing concern in the country,” she said in her remarks. “About 700 women die each year in the U.S. due to pregnancy or delivery complications.”

Nearly two-thirds of those deaths are preventable, she said.

Rural America’s higher maternal mortality rate “is particularly concerning to me… because early in my career, I worked on a healthy babies program and here we are… decades later… dealing with the same challenges… some of which have gotten worse,” Verna said. “Statistics show that pregnancy-related mortality deaths have almost doubled in the last 30 years.”

Since Verna’s speech in May, there’s been lots of discussion and fact-finding, said Katy Backes Kozhimannil, director of the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center.

A June 12 Summit on Rural Maternal Health hosted by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid prompted a lot of good discussion, Kozhimannil said. “But things aren’t changing fast enough for rural women,” she said. “I think the administration got a lot of input for rural maternal health, and I’m looking forward to the recommendation and resources that come out of that meeting.”

The most important part of new maternity legislation is collecting data to help understand the issue, Kozhimannil said.

“We don’t know why maternal deaths are increasing because we don’t collect enough information,” she said. “Only 46 states have maternal death review committees, and only two states in the U.S. require that there be anyone from a rural community on those review committees. That’s important because as a review committee can say ‘Oh, she should have been given a blood transfusion.’ As a rural hospital though, you may not have the equipment to do that. If there are no rural voices at the table to point that out, you won’t ever get enough accurate information.”

Some rural maternity deaths result from women’s lack of access to health care and OB/GYN services, experts say.

“Overall, rural women are less likely to receive any preventative health care and screenings,” wrote Sharon T. Phelan, M.D., in a report for Contemporary OB/GYN. “Fewer than half of rural women live within a 30-minute drive to a hospital with perinatal services, and over 10 percent have a drive of 100 miles or more. Some states, such as Wyoming, have no tertiary care centers for pregnant women at all.”

In 2010, nearly half of all the counties in the U.S. lacked obstetrician-gynecologist services, according to the American Council of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

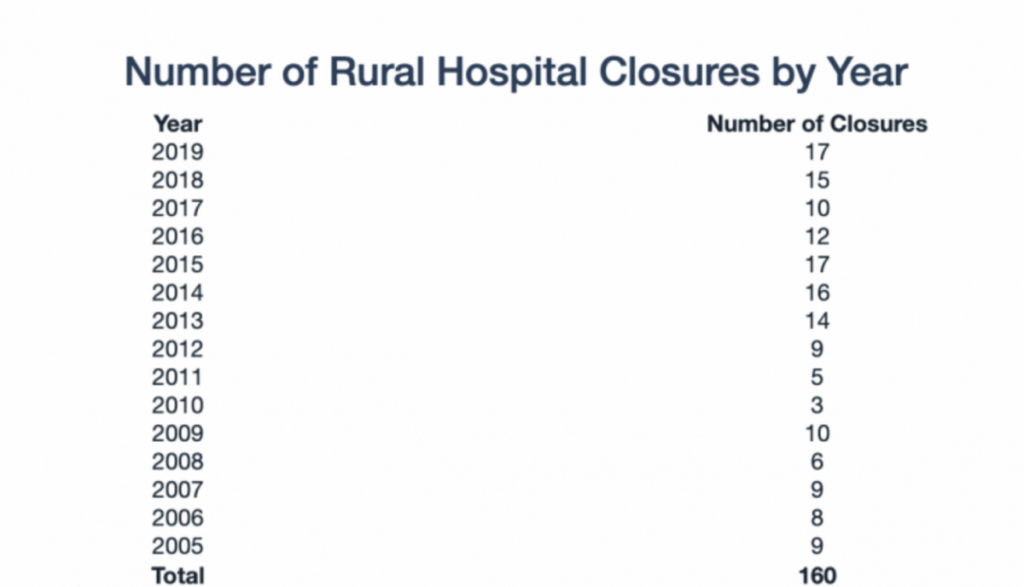

In some cases, this is due to hospital closures. As of March 20, 2019, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed across the country. Nearly a quarter of all rural hospitals are at risk of closure, with more than 400 experiencing significant financial challenges, according to a report by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina.

In some cases, however, hospitals in rural areas have just stopped delivering babies, mostly for economic reasons. In Iowa over the last two decades, more than 30 small rural hospitals have stopped deliveries.

Hansen Family Hospital in Iowa Falls, Iowa, stopped delivering babies in 2018. It was one of eight hospitals in Iowa to stop obstetric services that year. According to its CEO Doug Morse, delivering babies was a losing proposition. For the 86 deliveries the hospital saw per year, the hospital was losing nearly $1 million, Morse told Iowa Public Radio.

Besides access to healthcare, rural America’s greater incidence of obesity, cancer, cardiovascular disease, opioid use and violent deaths also play a role, Phelan wrote.

Torres Small said her bill would expand telehealth to include obstetrics and launch a training initiative to help family practitioners, doulas, midwives and other health professionals provide maternity services in areas where there may not be any OB/GYNs. It would also collect maternal-mortality data that includes the mothers’ sociocultural and geographic data.

“One issue I hear about any time I am home in New Mexico is the challenge rural residents face due to a lack of accessible healthcare providers, leading many to forego necessary care or to stretch their budgets to attend doctors’ appointments hours away,” Torres Small said in a statement.

“For pregnant women in rural districts like New Mexico’s Second District, they often have to spend hours on the road and cross state lines to attend the necessary prenatal appointments. Expectant mothers should have the peace of mind that no matter where they choose to start a family, they will have access to the resources they need to bring healthy babies into the world.”

In August, Torres Small and the rest of the New Mexico delegation announced that the CDC would be awarding the New Mexico Department of Health a $298,989 grant for that state’s agencies to manage the Maternal Mortality Review Committees. The money will be used to “study maternal mortality cases and identify prevention practices that can put a stop to these tragic deaths,” according to a press release from Torres Small’s office.

Torres Small’s Rural MOMS bill has been referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. A companion bill in the Senate, S 2373, sponsored by Senator Tina Smith, D-Minnesota, was introduced this summer as well. It too was referred to committee and is currently in the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions.

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.