To tackle a growing problem among young people, and fewer mental health professionals in rural areas, school leaders have joined a pilot project where students can talk with mental health therapists via a two-way video chat.

In rural areas, access to mental health services can be limited, sometimes even more so for teens and children. And the need for these services is growing, so one Midwestern school is using technology to help bridge this gap.

Two hours south of Indianapolis is Orleans, a farming and manufacturing town, population 2,000. The highway into town passes the junior-senior high school, which sits on a large lawn. Inside, a row of basketballs lines the top shelf in Principal Chris Stevens’ office.

They’re a symbol of rural Indiana, where schools — and basketball — are often the heart of community life. Many young people in these communities, and across the state, share something else: a struggle with mental illness.

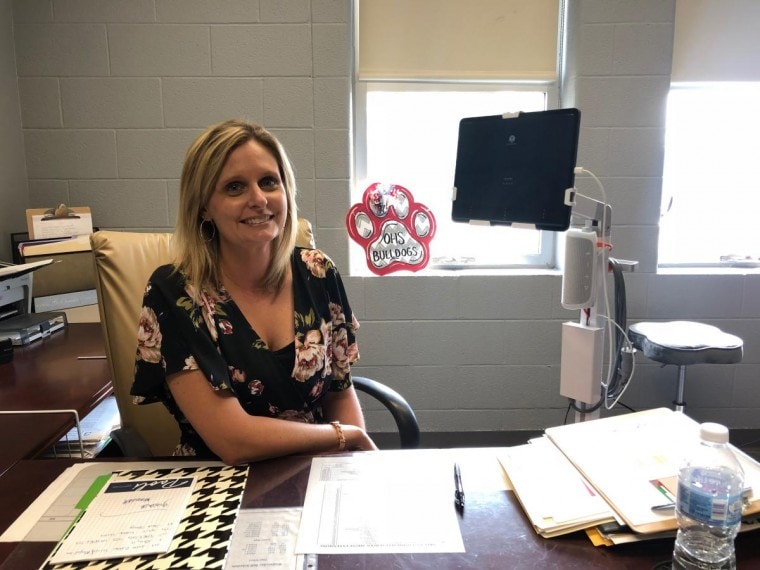

To tackle this growing problem, Orleans leaders are involved in a pilot project to help students. In the corner of Stevens’ office is a mobile stand with an iPad and speaker; students can use it to talk with therapists at IU Health via a two-way video chat.

“It’s been overwhelming as far as the amount of people … who either support it or have come forward and saying, ‘I want to be on this list,’” Stevens says.

School guidance counselor Kristin Bye says students tend to struggle with depression and anxiety. Others are dealing with traumatic childhood experiences.

“A lot of our students are being raised maybe by grandparents or in non-traditional homes,” Bye says. “There’s a lot of past trauma.”

And while Orleans has some nearby options for mental health services, that doesn’t mean students can easily access them.

“Parents either work and they find it difficult to get off work, or they are worried about insurance or their child missing school,” Bye says. “If they go to Centerstone at Bedford, that’s a 20-minute drive up a 20-minute drive back, plus the session itself.”

Parental consent is required for students to participate in the new service — generally known as telehealth. The consent issue has stirred debate as lawmakers tried to tackle the rate of Indiana young adults considering suicide –– one of the highest in the nation.

Shannon Mace of the National Council for Behavioral Health says there’s growing evidence that telehealth is an effective way to deliver mental health services. However, legal and logistical red tape have slowed the rollout of these services.

“So once you get over the hurdle of just being able to invest in the infrastructure itself, then they need to find a way in order to be reimbursed for the services that they’re providing,” she says.

Reimbursing for telehealth services can be tricky, because policies vary by state or insurance provider. And initially, incentives for telehealth services were aimed at physical health.

“So since then, behavioral health providers have really been playing catch up,” Mace says.

Insurer CareSource partnered with Orleans Jr/Sr High School to donate equipment and set up the services. The company says insurance won’t be a barrier for Orleans students who need treatment.

“We’d love to have this option available in every rural school setting if it’s successful,” says CareSource Indiana Market President Steve Smitherman.

The pilot project took about two years to get off the ground. And as schools are increasingly responsible for students’ mental health needs, it remains to be seen if this is a viable option for other districts.

“It is possible, I think you definitely still have to have the correct players in the game,” says Carrie Hesler, project manager for IU Health. “Access to funding to get the equipment, I think, would be one of the biggest barriers.”

IU Health says a school would need to purchase the $3,500 equipment, find a provider and navigate health insurance. And deal with two bureaucracies.

“We found out though, that our small school bureaucracy kind of works a little faster than some of the hospital bureaucracies,” Stevens says, laughing. “So some things took a little bit of time.”

He adds that doing this work means making sure everyone is on the same page.

“Not just small schools, but in every school, the workload is tremendous, and the needs are sometimes immediate,” he says. “But I feel like by us being proactive, that’s going to pay dividends in the long run for us and our kids.”

Results of the pilot — including grades, disciplinary records, missed school days and reduced depression and anxiety — will be tracked.

People in need can call a suicide hotline number at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255) to reach a trained counselor. The national crisis text line can be accessed by texting CONNECT to 741741.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health. It was originally published by the Daily Yonder.