Life as empty nesters was on the horizon for Lisa Robbins and her husband Brent. They had raised two children and were enjoying helping them with their two grandchildren. But in 2016, police arrested Lisa’s daughter Mollie.

“She got caught using drugs, shooting up in her vehicle in a convenience store parking lot,” Lisa said. “And so she went to jail.”

Mollie was pregnant at the time of her arrest. Lisa said it had been months since Mollie, now 24, had gotten any prenatal care.

“At that time, she was five-and-a-half months pregnant and she hadn’t had but one visit to the doctor up to that point.”

Mollie was using heroin, meth and opioid painkillers. The family worried her drug use would put her baby at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome or NAS, a condition where babies are born in withdrawal from drugs their mothers used during pregnancy.

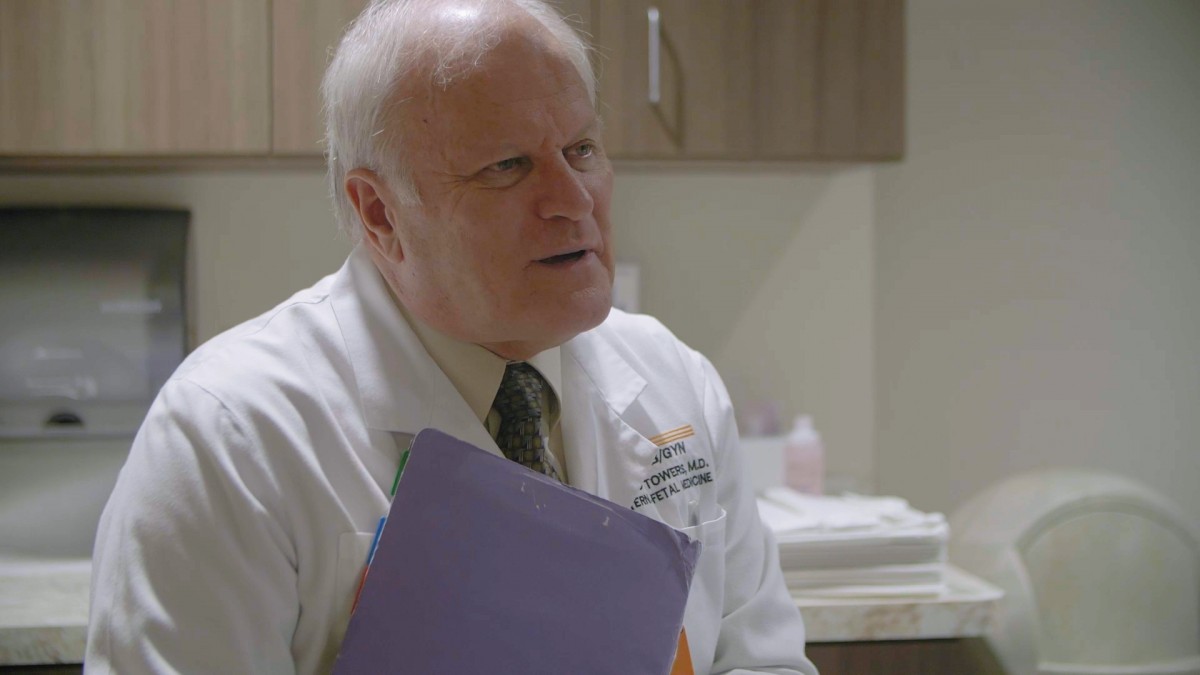

Mollie asked for help and the Robbins took her to High Risk Obstetrical Consultants, a clinic at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville that specializes in treating opioid-affected pregnant women and babies. There, Mollie received prenatal care and underwent medically supervised detox before her daughter Adaline Grace, who the family calls Addie, was born.

“Addie was born very healthy, six-and-a-half pounds, no NAS. She did not spend a single moment in the [Neonatal Intensive Care Unit]. So, we were very blessed for her to be born as healthy as she was and then to be fully weaned [from opioids],” Lisa said.

It was April 2017. Mollie maintained her recovery for a while after that, Lisa said, but one night, she went out with the baby and didn’t come home. A few days later, Mollie’s in-laws called the Robbins to say Adaline was at their house.

When Mollie resurfaced, police arrested her for violating her probation and sent her back to jail. Later, a judge granted Lisa, 50, and Brent, 54, custody of Adaline until she turns 18, or until Mollie petitions the court for custody.

“I didn’t want to raise another child and I feel guilty for that. But I’m a Christian woman. So I started praying and I said, ‘God, you show me what I need to do,’” Lisa said.

“There was no other option but for me to take care of Adaline, to help any way I could. If it meant I brought Mollie home, she lived with us and I took care of both of them, then that’s what I was going to do,” she said. “And so now we have Adaline, and to look back, I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

The Robbins are among the thousands of grandparents across Appalachia who are stepping in to raise grandchildren because their own children suffer from addiction, are incarcerated, or died due to a drug overdose.

Nationally, the number of children living with grandparents, relatives and close family friends has jumped nearly 18 percent over the last decade to more than 2.7 million. The increase is linked in part to the nation’s opioid epidemic, according to a report from the nonprofit advocacy group Generations United.

East Tennessee, where Lisa Robbins is raising Adaline, is seeing a similar increase in grandparent-headed households as many communities are especially hard-hit by both the opioid epidemic and neonatal abstinence syndrome.

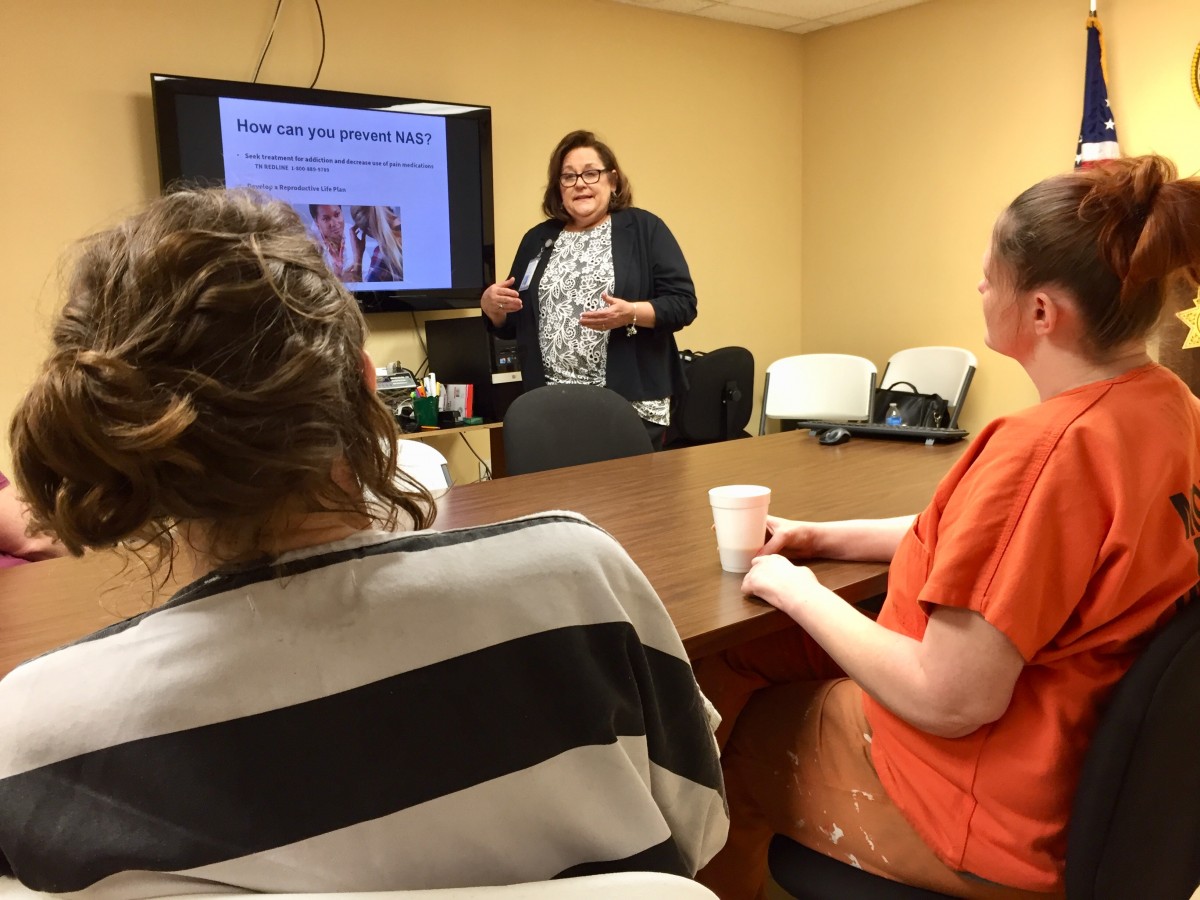

“In Monroe County, it’s like 65 percent of the babies born have somehow been born drug-dependent,” said Teresa Harrill, health department director for both Monroe and Loudoun Counties. According to the East Tennessee Regional Health Office, in 2017, 67 percent of the babies born in Monroe County had been exposed to a prescription medication in utero.

NAS and addiction are changing many families’ way of life in the region.

“We see a lot of women that already have children, that, either their child is in state custody, or grandparents or family members are raising their children while they’re incarcerated,” Harrill said.

The Robbins family lives in Maryville, about an hour south of Knoxville. Their white, wood-framed house sits perched atop a rise at the end of a long winding driveway not far from Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Children’s toys, freshly chopped firewood and a brick-red chicken coop sit in the yard. In the driveway, a car license plate displays a verse from the Bible, John 3:16: For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son.

It’s a rural area of rolling hills, two-lane roads dotted with churches, horse stables and lush farmland.

On a recent Sunday morning, the cool air reverberated with a country chorus of birds, frogs, cows and chickens.

Lisa and her mother Linda were busy in the kitchen packing coolers for a cookout after church.

Underfoot, Adaline, now 2 years old, padded into and out of the room, holding a sippy cup and asking for milk.

“My job was to be a grandmother, but my job now is as a mother to my grandchild. She’s my responsibility 24/7. I’m supposed to be teaching Mollie how to be a mom, and that’s hard,” Lisa said. “God intended us to be parents as young people. I mean, I don’t know any other way to put it, but you get tired. When you’re younger you think, ‘oh, I have to clean house, I have to have it a certain way.’ But as you’re older you realize that’s not what’s important–– it’s the baby or the child.”

Lisa, whose grandchildren call her Gaga, also works a full-time job in Knoxville. Her daily commute has become her time to gather her thoughts and enjoy a moment of quiet.

Church is a source of strength for the Robbins. She and Brent have been open in their church about Mollie’s drug use–– that’s how Lisa recently discovered Adaline isn’t the only child in the congregation whose mother has struggled with addiction.

It helps to talk about it, Lisa said, hoping that by sharing her family’s experience, she could help other families touched by the opioid epidemic and help break the stigma surrounding addiction and NAS in Appalachia.

Brent said his stepdaughter Mollie’s years of drug addiction have been difficult. He recalls the anxiety and fear of countless sleepless nights spent worrying she’d overdose and die.

“There were times [when] I wondered if we were going to have a service at a graveyard,” he said, “instead of a dedication service [for Adaline] in church.”

Mollie’s addiction has also taken an unexpected toll on his family’s bottom line.

“It’s cost us a lot of money to put her through drug rehab and stuff– $5,000 out of our savings– and I’m 54 and I’m looking forward to retiring and that’s 5,000 less dollars. That’s part of it though. If it saved her from overdosing, then it was worth it,” Brent said.

This spring, Mollie experienced another relapse and is currently back in rehab.

Despite the financial burdens and the challenges of working full-time, being a grandfather to his other grandchildren while also being a dad all over again to Adaline at his age, Brent said he wouldn’t change a thing.

“Because Addie is my whole world. When you come home from work and you have a little girl running to the top of the steps hollering papaw, papaw, papaw,” he said, fighting back tears, “that’s something that I can’t describe.”

Brent and Lisa have chosen to take care of Adaline, but don’t hide from her that they are in fact her grandparents, not her parents.

“Sometimes she’ll call me mom and I want to correct her because I want her to realize her mom’s as important to her as I am,” Lisa said. “And, of course, selfishly sometimes I want to be ‘mom’ but I can’t. I have to draw the line.”

Lisa and Brent both stress they hope Mollie will one day get back on her feet and be ready to parent Adaline full-time. For now, they’re focused on raising their granddaughter as Mollie continues to work on her recovery.

This story is part of the series Born Exposed, exploring access to medical and rehabilitative care in Appalachia for opioid-affected women and their babies. Born Exposed is a project of 100 Days in Appalachia, West Virginia Public Broadcasting and the Ohio Valley ReSource.