Spend a Monday at the Boone County, West Virginia, courthouse, and you’ll see judges and public attorneys overwhelmed with a surging number of child abuse and neglect cases.

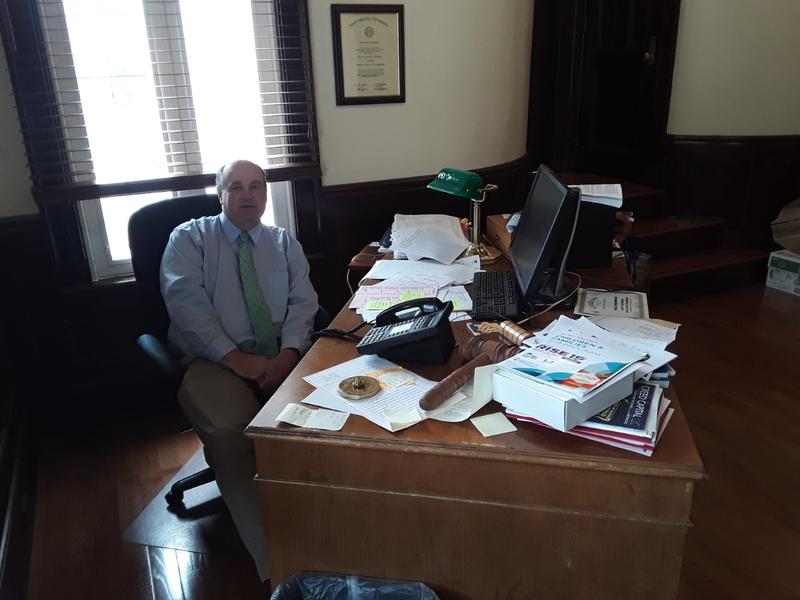

Mondays are reserved in Boone County for abuse and neglect hearings. Circuit Judge Will Thompson for Boone and Lincoln counties said he usually gets about 30 hearings each week. On his busiest days, he’s dealt with around 50.

Each week’s docket is made of several families who are in a different place in the abuse and neglect process: parents who have just been served petitions threatening termination of parental rights; parents working on an improvement plan, issued by the judge, to avoid losing their kids; parents who have veered from the plan and some close to finishing; parents who get their kids back and those who relinquish that right. There are adoptions, but many kids end upwards of the state until they reach 18.

There are often what the judge refers to as “empty chairs”— about half of the hearings last Monday, Aug. 26, were no-shows, in which parents didn’t attend their own hearings.

“We’re drowning in child abuse and neglect cases,” said attorney Leonard Scott Briscoe. Briscoe is appointed by Thompson to serve as a guardian ad litem for Boone County, meaning he represents the children in these abuse and neglect cases and in juvenile cases. Briscoe said on Monday he’s working with roughly 300 cases.

“It’s more than (Child Protective Services) can handle, it’s more than the prosecutor can handle, and it’s more than the judge can handle. It was never a part of the docket like it is now.”

Boone County, like the rest of West Virginia, has complex social and economic problems. Most of the families in the judge’s abuse and neglect docket are dealing with substance use disorder — several reports have emerged showing Boone County as one of West Virginia’s most hard hit by the opioid crisis. That includes a report from the American Enterprise Institute in March 2018, which shows Boone County had the highest cost per capita when it comes to dealing with the opioid crisis.

Judge Thompson, a Boone County native, doesn’t have the magic answer to all of his community’s problems, but, starting after Sept. 2, his court and two others in the state are trying something new.

“We will start taking referrals for family treatment court,” Thompson said. “And it’s a court where we’re going to apply the lessons we’ve learned in our drug courts to the abuse and neglect model.”

Family Treatment Court is a Type of ‘Problem-Solving’ Court

Family treatment court and drug court are two types of “problem-solving courts” that exist nationwide, where the court implements a sort of “behavior modification” strategy instead of incarceration.

West Virginia has had drug courts for several years. Judge Thompson himself leads a few drug courts for adults and juveniles in Boone County.

Boone, Randolph and Ohio counties will be the first in the state to offer family treatment court to their residents. Thompson said he’s grateful to the West Virginia Legislature for passing House Bill 3057 in the most recent session, which allows for the creation of family treatment court. The program has also received support from the state’s Supreme Court.

In drug court, participants can avoid jail time by following a plan from the judge, designed to turn their lives around. Requirements can include treatment, finding employment or going back to school.

Child abuse and neglect cases differ from drug offenses in that they’re not criminal charges — parents don’t risk going to jail, they risk losing parental rights.

But with most abuse and neglect cases being addiction-related, Thompson says family treatment court is what some parents need to kick addiction and reunite with their kids.

“We want to be able to put these children back with their families in a safe and loving environment,” Thompson said. “We are in the midst of an incredible crisis. For every child we can put in a good home, that’s a victory for that child.”

Thompson says family treatment court will be a more involved process for parents than the existing abuse and neglect system. In the traditional model, Thompson meets with families trying to get their kids back every six to eight weeks to address any roadblocks.

Those meetings will become weekly in family treatment court.

“The court — that being me, as well as the treatment team — is going to know on a weekly basis how that family is doing,” Judge Thompson said. “And how that will help is, if the family’s not doing well, what do we need to fix that? Do we need to increase the services? Do we need to have more involvement with that family? Or, if that family is doing well, what do we need to further this case along?”

Parents will have access to more resources for treatment, and parents will see their kids more regularly. Right now, Thompson said some parents must go through several drug screenings before having even a supervised visit with a child.

“We have decided from the beginning that we’re not going to use visits as a behavioral response, where it’s not going to be a sanction or a reward because we’re not sanctioning the children for their parents’ conduct,” he said.

Thompson said kids will be involved in the process as much as they safely can. He said there will be dedicated professionals available to talk with the parents and supervise visits.

“The children will be encouraged to talk to the supervisors to say how a visit went,” Thompson said. “Their needs and wants are going to be addressed as much as possible.”

Many Aren’t Sure What to Expect from Family Treatment Court

A week before the court was expected to begin taking referrals, many in the courtroom who are usually present for abuse and neglect hearings said they couldn’t spell out how they hope the system will change with family treatment court.

“I, at this point, am willing to try anything and everything,” said Briscoe, who’s in the courtroom every Monday. “I hope that a better focus and more time spent with these families, with a better quality system, will improve the rates of success with reunification, for the family.”

Kassie Ball is a public defender appointed by the court to help parents in these abuse and neglect cases.

“There’s so many unknowns right now, going into it,” she said of family treatment court. “I’ve read the plan of what my clients would be expected to do. My clients, when they see a long list of things, they can get overwhelmed, so they think, ‘Oh, I could never do that.’ I think the challenge for me would be condensing that [list], so it sounds like something they can do.”

Ball said she’s also concerned about the commitment her clients will be making when many are experiencing homelessness, making communication difficult.

Thompson says he and others hope to know more about family treatment court in about a month. Boone County will hold a press event from the courthouse in Madison on Oct. 7 to provide an update on the program. By then, Thompson says he hopes to have about 10 to 12 families participating.

Many people working in the Boone County courthouse said they do not believe family treatment court is about reaching record numbers of families, but rather it’s about helping as many children as possible.

“You know, everybody’s talking about the numbers of foster care children,” Judge Thompson said. “Children don’t care about numbers. So, for every child that I’m able to put back, that’s a huge victory for that child. Every time I do that, that’s a big victory for that child.”

Emily Allen is a Report for America corps member.

This article was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.