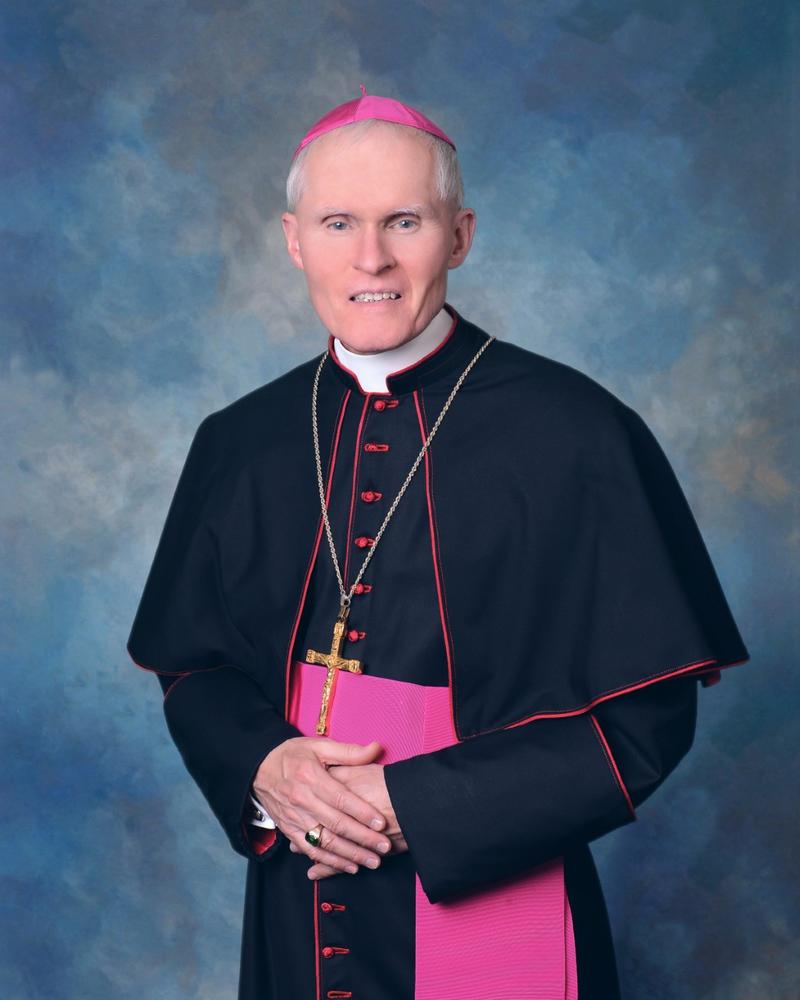

West Virginia’s new Roman Catholic bishop was installed late last month at the Cathedral of St. Joseph in Wheeling. Bishop Mark Brennan was previously auxiliary bishop of Baltimore.

Pope Francis named the 72-year-old Brennan to replace Bishop Michael Bransfield, who resigned in September 2018 amid allegations of sexual and financial misconduct. Glynis Board spoke with the new bishop. Here’s some of that conversation.

**Editor’s Note: The following has been edited for clarity and length.

GB: The former Bishop Michael Bransfield left the diocese in a crisis of confidence. Archbishop Lori described a culture of fear that was created under his tenure, and there were measures put in place to try to ensure a higher degree of transparency and safeguards against abuse. What actions do you hope will address that eroded trust?

MB: I’ve long believed the only way to overcome evil is with good. You have to just do good things. Our faith is not meant to be sterile, it’s meant to be fertile, to produce good things. So to try to live our faith well, and to the works of charity and justice that our faith really propels us to engage in — that’s I think how you overcome bad behavior over the past. You can’t ignore it the past, you can’t deny that it happened. On the other hand, you also can look forward and try to live a better way. And I hope that I can be the kind of shepherd for the flock of this diocese that will lead by example, not just a words, to overcome a legacy of mistrust and fear and by a different kind of style of leadership.

GB: Are there decisions yet to be made that have anything to do with Michael Bransfield, that you have to make?

MB: I think as you’re probably well aware of the Holy See imposed on Bishop Bransfield two very significant prohibitions. And they are significant. He was planning to retire here. I’ve seen the very nice apartment that was built for him. He’s not going to get to live there. He’s not allowed by the pope to live in the state of West Virginia. The second one is that he’s not allowed to celebrate any public liturgy. The Catholic mass is that is the most common liturgy, but a baptism ceremony, a funeral outside of mass, a wedding ceremony outside of mass, those are liturgies too. For someone who has been doing that for nearly 50 years to be told, ‘You can’t do that anymore,’ no public masses, no public luxury of any kind — it’s a very significant prohibition.

What I’m asked to do is to oversee a process of him making some kind of amendment for the damage he caused to individuals and to the diocese. And that is in process. I’ve already begun consulting with people here. We were doing some analysis of spending to see what is an appropriate way to ask him to make amends. If he cooperates with this process it will show, I think, another side of him, which I hope we will see. If it is not cooperate we’ll still be able to impose a kind of amendment process on our own. [It would be] better with his cooperation, but it can still be done without it.

GB: It’s increasingly well known that the Wheeling-Charleston Diocese is one of the more wealthy dioceses in the country. And yet here we are sitting in one of the poorest states and even one of the poorest neighborhoods in this region. How is that wealth being used to combat those cycles of poverty? Or how do you think it could be used in the future?

MB: There are things that I have learned there already, things that are done by the diocese with the money that it has — some of which comes from somebody who left us some oil wells down in Texas, and mineral rights somewhere. I’m going to find out more about that. At any rate, yes, there’s an endowment which seems to be fairly large — several hundred million dollars. The diocese is using that to support small schools and parishes that otherwise would otherwise close. They can’t maintain themselves. I think there are efforts being made by Catholic Charities in West Virginia to assist in in meeting the opioid crisis, which, this is like the epicenter for the whole country, from what I’ve learned, and I’m going to see if we can do more — remember, I’ve only been bishop here for eight days, so there’s a lot more for me to learn — but the resources are being used in a healthy way to sustain good works of the church and its schools and parishes and agencies.

GB: Michael Bransfield retired as many bishops do at 75 — and forgive me if this is an ageist question — some parishioners have expressed concerns since you’re already into your 70s that you won’t be here long enough to sustain positive change. Can you address that concern?

MB: Sure. It was intimated to me when I was asked, would I come here, that the room would be very flexible about that 75 age limit. Now, I could drop dead tomorrow. My doctor at an appointment on the 30th of July, he said Father Brennan, your parents gave you good genes, and you’ve taken pretty good care of them. So I have pretty good health, stamina, and keep going. So assuming that I can then I think 75 will come and go without any change in the leadership here.

Some Catholics may remember — and it was a boy when this happened — a fellow named Roncalli was elected Pope by the Cardinals 1958. And he was I think 77 years old. He lived another four or five years. He called the Second Vatican Council which just had a tremendous impact of life of the Catholic Church worldwide. In his brief, brief time as Pope.

It is possible to get something done if you work at it with purpose and determination and trusting God. So I hope that all that can be true.

This article was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.