One-month-old Cayden wakes with a fierce cry and clenched fists as a nurse places her on a metal scale to check her weight. When she was born, the infant dressed in tiny pink socks, flowery leggings and a bright yellow polkadot top weighed 6 pounds, 7 ounces and was at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome.

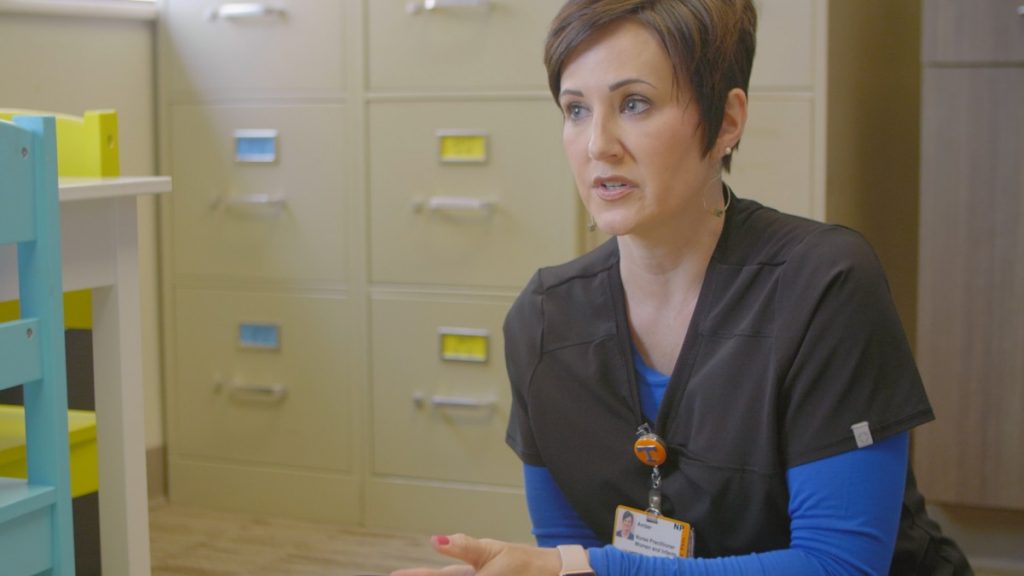

“Have you noticed any tremors, tight muscles?” Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Amber Knapper asked Cayden’s mother.

Tight muscles and tremors are among a long list of symptoms connected to neonatal abstinence syndrome, commonly known as NAS, a condition where babies are born in withdrawal from opioid drugs their mothers used during pregnancy.

Other symptoms can typically include seizures, diarrhea, irritability, fever, high-pitched and excessive crying, difficulty breathing, poor sleep and difficulty feeding. Babies exposed to opioids in utero could also be at risk for long-term developmental and educational delays.

This is Cayden’s first checkup since leaving the hospital’s newborn intensive care unit, and Knapper examines the baby closely, asking about her appetite, her breastfeeding and sleep patterns.

“The big thing I want to do today,” she said, “is, I want to get her down to a dry diaper, I will get her weight, length, measure her head and just see how much she has grown.”

Cayden showed no signs of NAS at birth. Nonetheless, this is the first of many follow-up visits that she’ll undergo over the next three years.

“Not only do we want to see all of the babies back that did have NAS and were in the NICU [Neonatal Intensive Care Unit] and treated, we also want to see these babies that did not have NAS, and we want to see how well they do– we want to compare,” Knapper said.

Knapper is part of an expert team at this University of Tennessee Medical Center clinic in Knoxville called High Risk Obstetrical Consultants. The clinic is tracking Cayden’s progress, and the progress of more than 600 other children, for a study investigating the long-term impacts of NAS in babies.

“We’re checking to make sure that they’re meeting all their milestones, developmental milestones– motor skills, speech, cognitive– and that they’re growing as they should,” Knapper said.

Cayden’s mother Callie Relford, a petite blonde in knee-high brown boots and blue jeans with her hair pulled back into a high ponytail, struggled with addiction for years before her daughter was born. Rocking the baby to sleep in her arms after the checkup, the 29-year old recalled her addiction to pain pills, which eventually led her to homelessness.

“There was no food to eat. You didn’t know what was going to happen the next day, if you was going to make it, if you was going to have something to eat, a roof over your head, if you was going to be able to shower. That was my life for a good six years, but a good four of it was literally living on the lake or in an abandoned house,” Relford said. “There was a lot of legal issues, I got in trouble a lot.”

She was already pregnant when Relford’s struggles with addiction landed her back behind bars in an East Tennessee county jail on drug-related charges.

“When I got there I was like, ‘I’m not about to have this child in jail,’” Relford said, “and so that’s why I needed to turn myself around and make sure she was OK and to keep her.”

Today, Relford and Cayden live at a group home with other new mothers and moms-to-be who are also in recovery.

She also has two other children, both boys, ages 12 and 5, who currently live with other family members.

Relford said she’s working on getting back on her feet and maintaining her sobriety so her boys can eventually live with her full-time.

“I know I’m going to have ups and downs, of course,” she said. “But I’m going to do the best I can to deal with them, cope with them, and do whatever it is I have to do to make sure that I don’t go back down that dark road again, and make sure that my kids have the best life that I can give them.”

It was during her sixth month of pregnancy when a jail program sent Relford to High Risk Obstetrical Consultants for her first prenatal check up. Relford worried the drugs she’d taken would hurt her baby. With the help of the clinic, she went through medically supervised detox and later, started on the medication Naltrexone to block her opioid cravings.

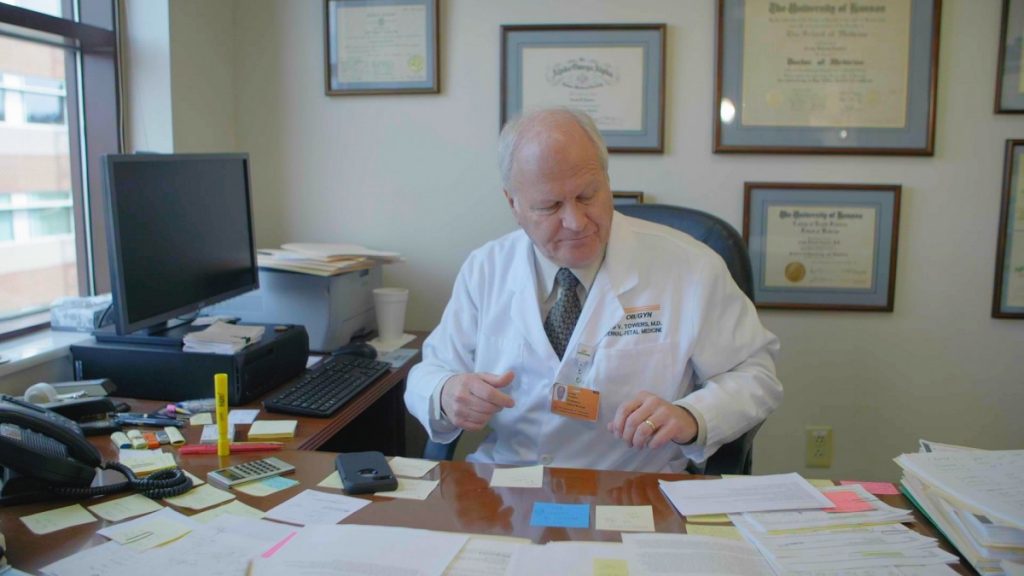

Maternal-fetal Medicine Physician Craig Towers oversaw Relford’s treatment during her pregnancy.

It was Towers’ idea in 2016 to dedicate one day per week at High Risk Obstetrical Consultants to treating opioid-affected women like Relford, with the goal of helping them get off drugs and deliver healthy babies born free of NAS. Towers said he saw the need to create a special program after dozens of pregnant women came to the clinic seeking help with addiction.

“When I came here, I was amazed at how many patients I had in our high-risk OB-GYN clinic that were addicted to opiates, much more than I had where I was from previously at that time, which was Wisconsin. And the patients had two things: the first thing they would say is, ‘I didn’t plan on getting pregnant,’ but the other was, ‘I don’t want to be on these drugs and have my babies suffer for what I’m doing,’” Towers said. “And I would tell them, like everyone else, that it’s not recommended to taper or detox off of opiates because, in theory, it can cause a stillbirth and harm the baby and lead to a poor pregnancy outcome.”

Towers was advising his patients based on the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ standard of care for pregnant women.

Eventually, he grew tired of hearing himself say the same thing over and over again, Towers said. He decided to review the medical literature on the safety of detox during pregnancy to put together a pamphlet for his patients, but was only able to find two studies on which the generally agreed-to medical advice was based. He wasn’t convinced.

“There’s no data to say that [detox] harms the baby or results in a poor pregnancy outcome,” Towers said.

But that view could be considered controversial. In the United States, detox during pregnancy has long been seen as too risky for expectant mothers and infants.

Most obstetricians recommend medically assisted treatment, also known as MAT, over detox for pregnant women addicted to opioids, using maintenance medications such as methadone, an opioid, to get them off of dangerous street drugs such as heroin and fentanyl. But the treatment itself still carries a risk of NAS.

MAT has been shown to be highly effective in helping pregnant women stay off of dangerous street drugs such as heroin and fentanyl. But the treatment itself still carries a risk of NAS.

Tennessee has been tracking NAS cases since 2013, and the state Department of Health reports maintenance medications are among the most common opioid sources of NAS in the state, which also include painkillers such as morphine, and heroin. In 2018, state numbers show 70 percent of infants diagnosed with NAS were exposed to MAT for the treatment of a substance-use disorder.

But Dr. Mishka Terplan, a professor in the departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychiatry at the Virginia Commonwealth University, said pharmacotherapy, or using medication, remains the gold standard for the treatment of opioid-use disorder in the U.S., not just in pregnancy but for all populations. Detox during pregnancy puts women at higher risk for relapse, overdose and the transmission of diseases, including Hepatitis C and HIV, he said.

“We know that the postpartum period is a time of increased vulnerabilities for disease recurrence. In many states that have been looking at this, overdose and overdose death is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality,” Terplan said, “and medication for opioid-use disorder protects against overdose and overdose death.”

Towers does follow the same standard of medically assisted treatment protocol at his Knoxville clinic, but it’s not the only option he gives his patients, it’s just the start.

“All of my patients who come in using illicit drugs, meaning that’s not prescribed to them – they’re getting it from a friend off the street or stealing or whatever – I get them into a maintenance program of methadone or buprenorphine,” Towers said.

Towers believes what’s most important is that the women he treats who struggle with opioid addiction find a path to recovery and get off of street drugs as quickly as possible. Once they’re stable, Towers’ patients choose whether they want to detox completely or remain on medically assisted treatment for the remainder of their pregnancy.

“Now, I have probably tapered off and detoxed over 700, maybe over 800 [patients] without a loss, knock on wood,” meaning without the loss of a pregnancy. “But we have a very strict program if they decide to do that.”

Towers is documenting these outcomes and leading several ongoing research studies designed to test the safety of detox during pregnancy. He’s hoping his results convince the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists that it is a safe option so that they’ll endorse the practice as an option for pregnant women.

“All I’m asking for is that women be given the choice,” he said.

The 2017 ACOG Committee Opinion on opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy states: “more research is needed to assess the safety (particularly regarding maternal relapse), efficacy, and long-term outcomes of medically supervised withdrawal.”

Towers acknowledges relapse remains a real concern. To help prevent it among his patients, the clinic provides a range of inpatient and outpatient services designed to support women throughout their pregnancies and after their babies are born.

Offering medical, prenatal, pediatrics and mental-health services all in one place is critical for this high-risk patient population, Towers said, because many patients do not have a driver’s license or access to a car.

“Almost all the women who don’t show up to my appointment will call and apologize and reschedule because they don’t have a ride.”

The clinic is working with a far-flung network of advocates and nonprofits across the East Tennessee region on an effort to increase transportation options for women at risk of delivering babies with NAS. They want to make it easier for these women to keep their prenatal and addiction-treatment appointments.

The need is urgent, Towers said, because according to the data he has collected, exposure to opioids in utero can potentially result in long-term issues for children. Towers recently published research suggesting some babies exposed to opioids, including both prescription drugs, like buprenorphine and methadone, and street drugs such as heroin, will experience developmental delays.

“There is a subset of babies that potentially have smaller head sizes, they have behavioral health issues, some of them have cognitive problems, some of them have visual dysfunction,” Towers said. “And we don’t know why some babies don’t exhibit that problem and others do.”

But the long-term effects of NAS are still subject to debate in some corners of the medical community. Towers said it could take another decade before researchers fully understand the condition’s impacts on babies and children.

Clinics like High Risk Obstetrical Consultants that offer pregnant women both a detox option and medically assisted treatment are hard to find. Some of the women 100 Days spoke to described feeling judged by other doctors in the past. Many said they were turned away from medical treatment because they used drugs.

Towers’ clinic sees hundreds of patients each year, including many who travel to Knoxville from all across Appalachia and the South for help, coming from as far away as West Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Many more come from small communities across rural East Tennessee.

The clinic’s substance abuse coordinator Emily Katz, who works closely with all of Towers’s patients at risk of delivering babies with NAS, said this population of pregnant, opioid-using women is especially vulnerable.

“They don’t trust anybody. They’re embarrassed,” Katz said, “and so many times we have heard from them, ‘you’re the first person that would listen or you’re the first person that I’ve told this to.’”

Katz lost her own brother to an overdose not long ago. The experience informs her work with patients.

Relationships are key to preventing relapse among pregnant women struggling with addiction— and preventing NAS in their infants, Katz said. Patients need someone to have their back through recovery from opioid addiction.

“They literally have burned either bridges with everybody or everybody in their family is actively using. So, we become like family.”

This story is part of the series Born Exposed, exploring access to medical and rehabilitative care in Appalachia for opioid-affected women and their babies. Born Exposed is a project of 100 Days in Appalachia, West Virginia Public Broadcasting and the Ohio Valley ReSource.