It looked like a climate strike was not going to happen in downtown Birmingham, Alabama.

In the Appalachian city, a group of hopeful high schoolers and middle schoolers planned to join hundreds of thousands of young people and adults from as many as 150 countries in a demonstration Friday as part of the Global Climate Strike. The strike comes just before a meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on September 23 and is meant to draw attention to the lack of action being taken to reverse or mitigate climate change.

In Birmingham, students planned to hold a protest in Linn Park, just across the street from City Hall. But it looked as if the event would be cancelled this week when the group was late submitting a permit request to gather in the public space.

Enter stalwart eighth-grader Stella Tarrant.

Stella, 14, wrote a letter to Birmingham Mayor Randall L. Woodfin, with a last-minute plea.

“ I wrote to him to see if he would get us a special permit,” she said. And he did.

Now, plans are moving forward for the Friday morning rally, without much surety in how many people will actually attend. But if interest on the event’s Facebook page is any indication, there’ll be a crowd.

“There are 200-and-something people who are either going or interested,” Stella said, ”and 5,000 people have seen our page.”

Among those striking will be seventh-grader Eric Ledvina. He has his immediate future and that of his friends in mind.

“I honestly don’t want to end up when I’m 20, that there is a lot of pollution and many species gone extinct and terrible weather. You can already see patterns of that,” he said.

One of the major goals of the climate strike week is to get more adults involved and for Eric, that means bringing his aunt, Anne Ledvina, along with him. Stella’s resolve to save the nearly cancelled event wasn’t lost on her.

“We couldn’t have done this climate strike without Stella taking the lead on this,” she said.

The roots of the youth climate strike movement began in late 2018, when then-15-year-old Greta Thunberg left school in Stockholm, Sweden, one Friday with a hand-drawn sign: ‘School strike for climate.’ (In Swedish, of course: ‘Skolstrejk for Klimatet,’ is a now-iconic phrase.) Her solo strike has since spurred thousands of youth climate strikes around the world.

Now, young people in Appalachia are joining supporters like Greta on the front lines of the strike, organizing events in their communities, like Stella, and encouraging people in the generations ahead of them to take a stand.

‘Most of My Family Denies It’

No doubt like many young climate activists popping up across Appalachia, 20-year-old Julia Alaimo meets resistance in her own family to even the notion of climate change.

“I never grew up in a household that cared about the environment or was interested in climate change. Actually, most of my family denies it,” said Alaimo, who attends the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

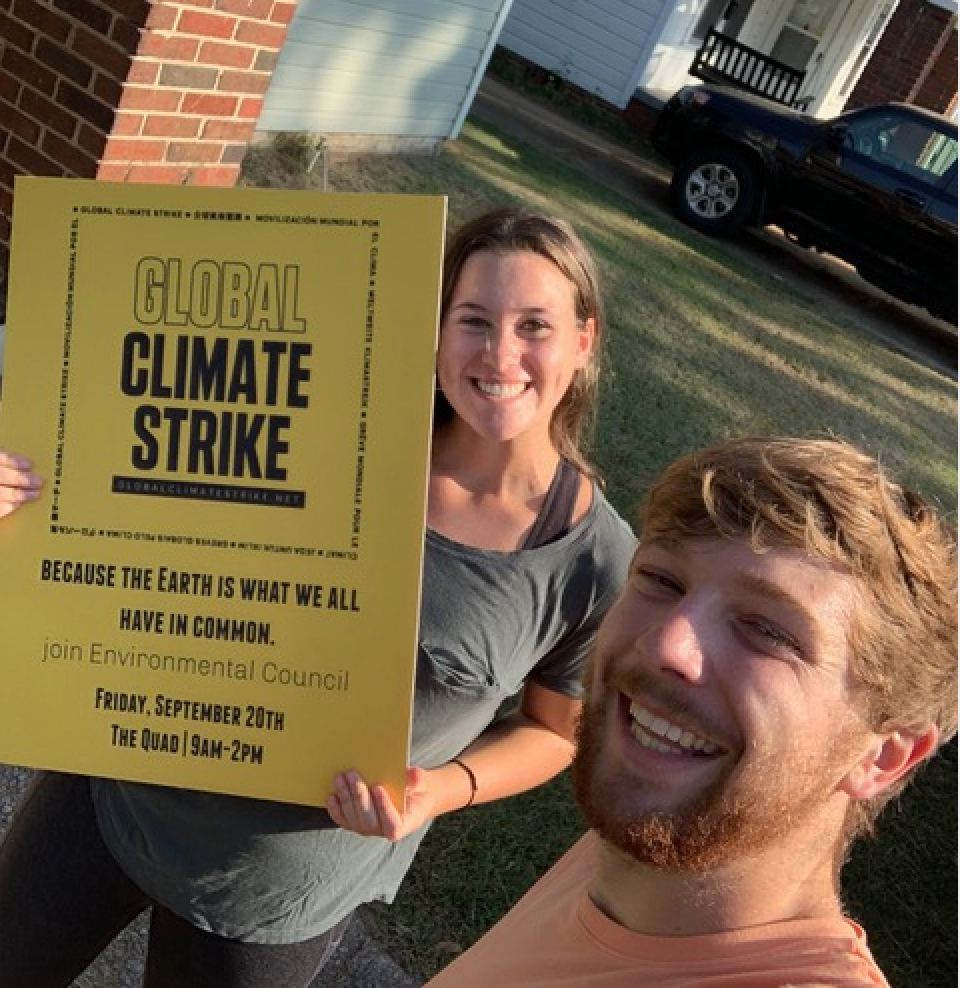

That hasn’t slowed her in the slightest. Alaimo is student president of The Environmental Council at the university and coordinator for a climate strike on the campus Quad, which also takes place Friday.

An environmental engineering major, Alaimo said she wants to focus not just her current activism, but her life’s work on the climate crisis.

“I’ve always wanted to solve environmental issues,” she said. “I think one big thing that we can do personally is try to help with policy change and influence people who are making large decisions around us that affect every one of us.”

A couple of days before the strike, she was at work on a speech to deliver at Friday’s strike, along with classmate and fellow climate striker, Nick Wright-Osment. Growing up with a mother who is a biologist, Wright-Osment tuned in early to awareness of the human race’s growing impact on the Earth’s operating system.

“I kind of grew up my whole life hearing, ‘Oh, we need to do something about global warming.’”

There is absolutely no time to waste, he said.

“I think the big key here is, as a message, we want people to realize that climate change is the number one issue. It should be for everybody,” Wright-Osment said. “This isn’t, like, a political thing. It’s a global threat that is extremely vital and extremely time-sensitive.”

Climate Class Is in Session

It’s a measure of the exploding activism around climate change that the strike was announced as a single-day event but has grown to a week’s worth of happenings, ending September 27. It’s another sign of the times that courses with titles like “People vs. The Planet: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Climate Change” are filling at Appalachian universities.

But they are, at least at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia, where 21-year-old Brandon Taylor, a double major in geography and Chinese studies, has signed up for the interdisciplinary humanities course this semester.

“With climate change becoming even more of a threat— seemingly every day, there’s a new story coming out— I want to shift away from just studying it,” Taylor said. “I’m moving towards more of, like, closer to activism.”

That’s why he’s participating in the climate strike event being planned at WVU, likely to be the largest Global Climate Strike event in the state.

Taylor will be joined by some of his classmates and his professor, Andrea Soccorsi, who created the class not just foster conversations about solutions, but also encourage collective action across disciplines.

“I am not a scientist, that’s the first thing that I always tell people,” Soccorsi said, who teaches a variety of English and writing courses. “We always think that this is an issue that the scientists are going to solve, but I’ve tried to show the students that they have something to bring to the table as well.”

In the classroom, her students explore the long tradition of eye-opening environmental literature, from Thoreau’s masterwork “Walden,” to Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” which kickstarted the environmental movement. They also work closely with local environmental organizations to advocate for change, including things as small as aiding businesses who are trying to swap out plastic straws for alternatives.

“There are no simple answers,” Soccorsi said, “but I think the first place is to begin having the conversation, which I’m not sure that we’ve done very successfully.”

Taylor is keenly aware that the future he and his generation will inherit depends on rapid, concerted action on huge global goals, such as the call to bring carbon emissions to net-zero within a decade.

“There’s a lot of work that needs to be done in a fairly short amount of time. But to not do it would be catastrophic for a lot of the world.”

‘How Do We Keep Appalachia from Burning?’

In Lynchburg, Virginia, he’s known as “Rev. Paul.”

And while he doesn’t fall into the definition of a young leader in Appalachia, Rev. Paul Boothby believes the stakes couldn’t be higher for youth in the region. That’s why he’s hosting a Global Climate Strike gathering at his 1st Unitarian Church of Lynchburg.

“Appalachia has depended on a relatively stable climate for a long time,” Boothby said, “and there are going to be ever-increasing extremes— between storms and drought and the movement of bio-regions in the generations to come.”

Hotter temperatures and a northward shift of species as a result are not just airy concepts. They are pressing concerns, said Boothby, for the sprawling forests of Appalachia, a region that encompasses all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states.

“Droughts are going to become more extreme. And that, of course, endangers the health of the forest, making forest fires all the more likely in the decades ahead,” he said. “So, how do we keep Appalachia from burning?”

Right now is the time to bring youth and adults together, to confront and address these stark possibilities, he said.

“Generations now have to do their part to take action.”

Douglas John Imbrogno is a freelance writer and podcast producer based in West Virginia. He is editor of the newsletter and podcast ChangingClimateTimes.substack.com. The newsletter is a co-sponsor of the Global Climate Crisis Rally on Sept. 26, 2019, in downtown Charleston, W.Va.