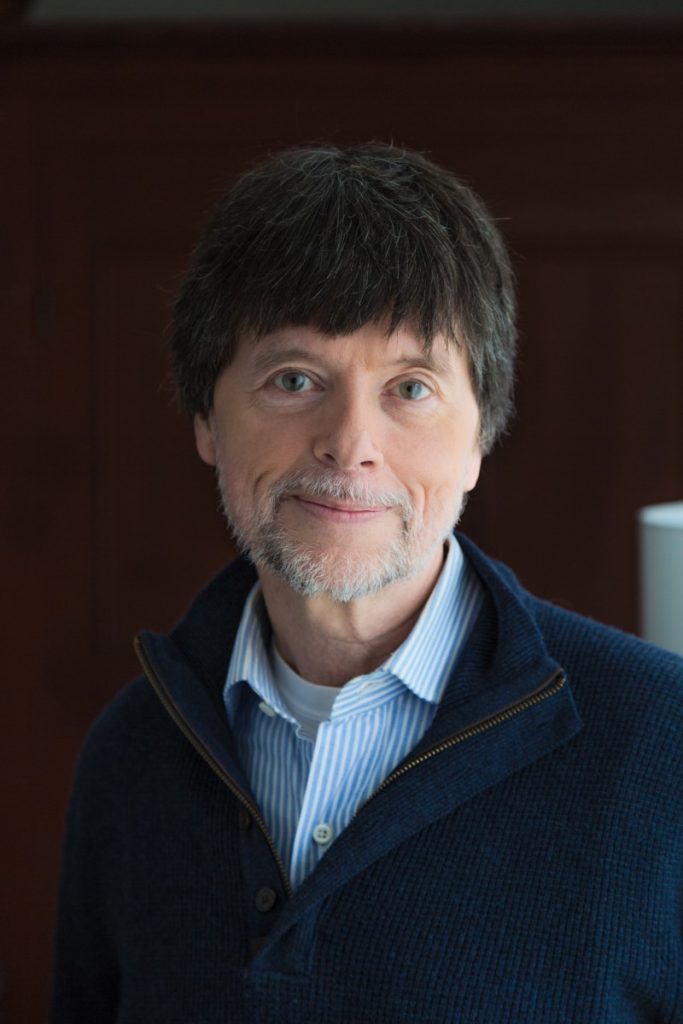

When rumors began circulating among the community of country music scholars that famed documentarian Ken Burns was turning his attention toward country music, I had mixed feelings.

To be sure, such a national platform for the telling of the genre’s history would provide an opportunity for a national— and even international— audience to engage with the work that my colleagues and I do every day. But it also is an opportunity to tell the story of a genre that I have loved since I was a kid.

This work not only documents country music’s history but considers why the genre has always attracted a diverse range of emotional responses from fans and detractors alike. I recalled the influence that his “Jazz” had on me as an aspiring jazz musician in my early twenties and thought of the remarkable power that documentary enterprises like Burns’s have to shape narratives and create a sense of belonging for their audiences.

But, as a country music scholar, I was also highly skeptical of Burns’s involvement in a country music project. His previous documentaries have often leaned on familiar historical narratives that privilege dominant perspectives on his subjects while only nodding toward voices of dissent and debate. As well, I am also deeply aware of Burns’s reliance on the insights of sometimes-problematic narrators, such as Confederate sympathizer Shelby Foote, whose work shaped Burns’s Civil War, or jazz conservator Wynton Marsalis, often to the exclusion of other historians and experts in the field.

And, as a well-produced and carefully promoted commercial property, Burns’s documentaries have extraordinary power to shape public understandings about their subjects for a generation or more, using their public television platform to overshadow the work of experts who have dedicated their careers to understanding the same subjects.

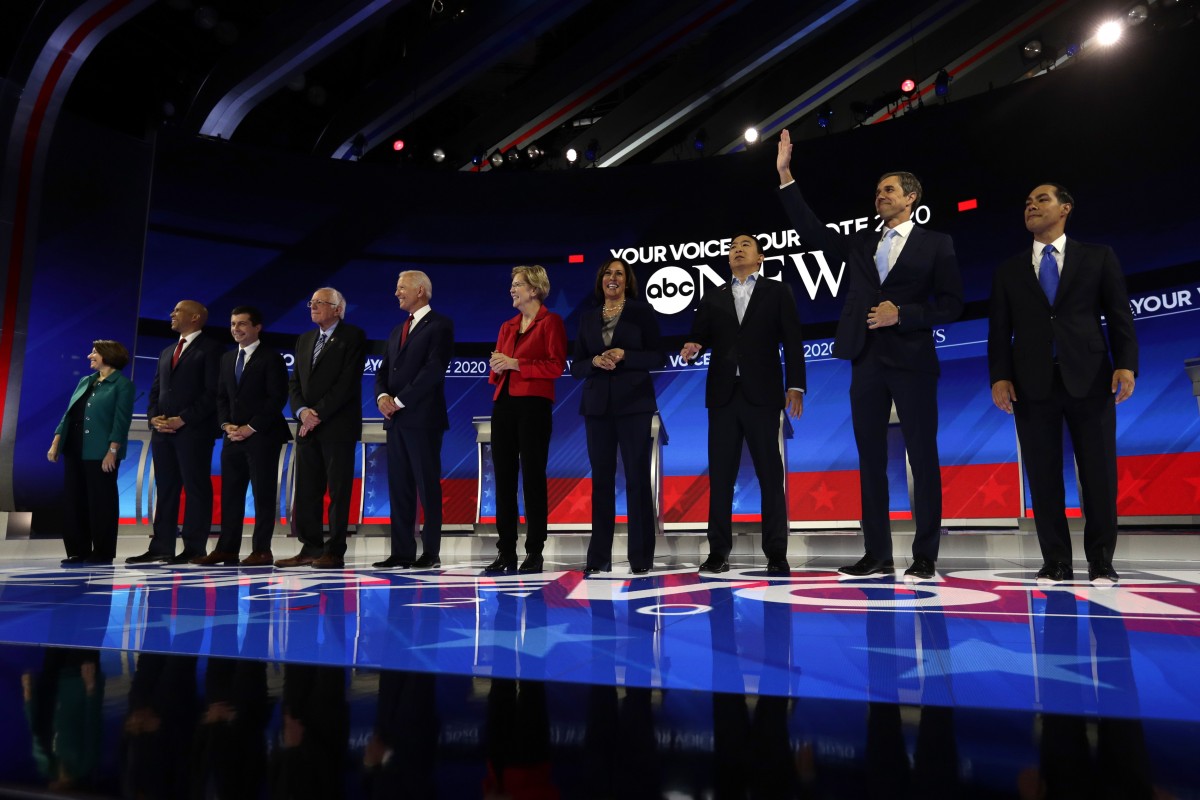

Burns’s “Country Music,” which airs on PBS for eight nights beginning on September 15, offers a familiar journey through the history of country music as a commercial popular music genre. Covering roughly 75 years from the production of the first “hillbilly” records in the early 1920s to the rise of stadium star Garth Brooks in the early 1990s, the 16-and-a-half-hours of “Country Music” showcase an impressive array of archival photographs (many of which have never been published previously) and interviews with dozens of Country Music Hall of Fame members and musicians who are well on their way to that honor.

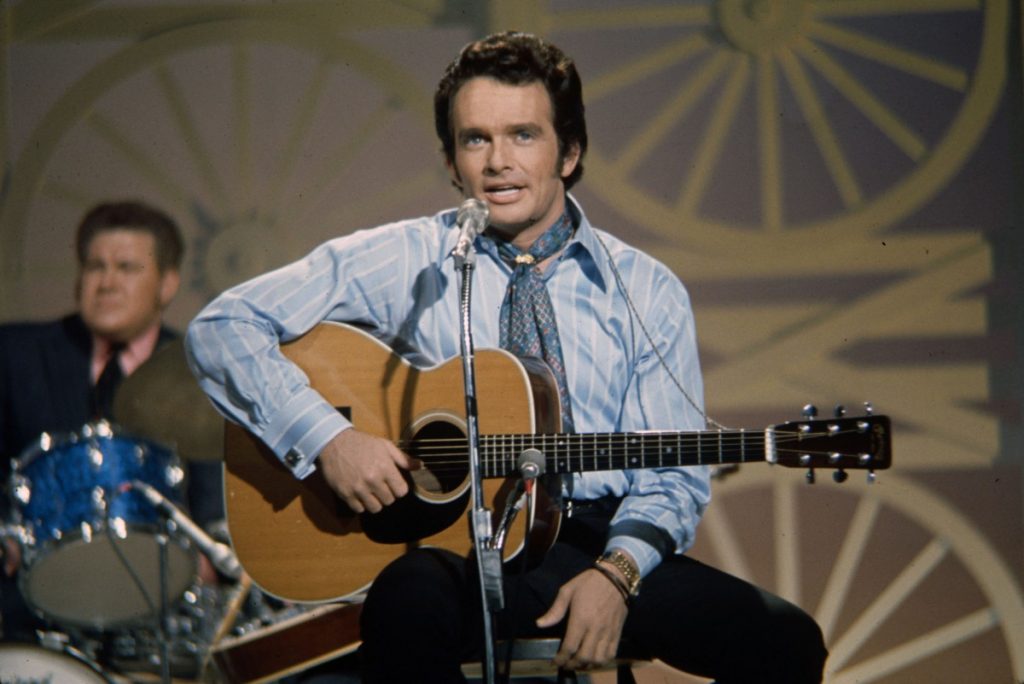

Country music fans will take particular note of the number of recently deceased artists– Merle Haggard, Jean Shepard, Little Jimmie Dickens– and industry leaders– Harold Bradley, Fred Foster– who appear in the series, often telling stories that have not previously been shared on the record. As well, an impressive soundtrack— typically one of the strengths of Burns’s documentaries— grounds the series in familiar sounds, evoking the old K-Tel and Time-Life collections that were so popular during the 1970s and 1980s.

Like many of Burns’ productions, “Country Music” leans heavily on the work of a single historian: Bill C. Malone. The choice of Malone is not surprising, as he literally wrote the book on country music. The eight episodes are structured carefully around the contents of his pioneering study, “Country Music, U.S.A.,” first published in 1968. It was the first narrative history of the genre and a standard text for anyone seeking a broad understanding of the musical style for more than five decades.

Malone’s understanding of country music is grounded in his own childhood experiences growing up on a farm in Texas in the 1940s, where he listened to the “Grand Ole Opry” on a Philco radio, and as a student at the University of Texas at Austin during the 1960s, where he participated in folk singing at a local beer joint owned by a yodeler and frequented by a young Janis Joplin.

For Malone, country music is a musical style that draws influence from African American, Mexican and Mexican American, and Anglo-American musics and filters those sounds and styles through the lived experiences of the white working class of the U.S. South. Although numerous scholars have critiqued this argument and provided ample data to challenge Malone’s “southern thesis,” “Country Music” works to affirm its southernness, nodding only occasionally to thriving country music communities in the Midwest (most notably in the second episode, which focuses on members of Chicago’s “National Barn Dance”) and otherwise neglecting the genre’s popularity in other regions of the U.S. and abroad.

Moreover, by the second episode, titled “Hard Times, 1933-45”, the documentary’s narrative centers not only around the South, but Nashville in particular– a city that has practically become a synonym for country music in the global consciousness.

Country music communities have always been obsessed with the genre’s history. In the 1920s, when it first appeared on commercial recordings, producers promoted the music as “old familiar tunes,” and such leaders as industrialist Henry Ford saw the music and its associated dances as a way of turning back the tide of urbanization and racial miscegenation. As new generations of country musicians came along in the 1930s and 1940s, they often imitated the sounds of such first-generation stars as the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, and included their music in repertoires to show their allegiance to tradition.

And by the mid-1960s, the recently formed Country Music Association was working to establish the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum to tell the genre’s story to visitors from around the world, a story that placed Nashville, the “Grand Ole Opry,” and the recording studios and publishing houses on Music Row at the center of the narrative, much to the exclusion of competing country music styles that were popularized in other music industry centers.

Like these historicizing acts, “Country Music” often treats the genre as the product of consensus, of mutual respect and of shared rewards. For example, in the final episode, “Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: 1984-1996”, viewers are introduced to Garth Brooks, the country music juggernaut who merged honky tonk songs and arena rock concert productions to dominate the country music landscape in the early 1990s. With the benefit of nearly three decades of hindsight, Brooks’ meteoric rise to international superstardom can be cast as a high point in the genre’s history, one that confirmed decades of work in the country music industry to prove that the genre could have widespread popular appeal.

But Brooks’s music and stage antics were also widely seen as a sign that country music had lost its soul, that the music was little more than a product to be bought and sold and that it no longer reflected the experiences of the working people who originally created it. Referencing one of the genre’s most influential artists, Hank Williams, Texas singer-songwriter Kinky Friedman even went so far as to brand Brooks “the anti-Hank,” garnering the support of a wide variety of disaffected country fans who preferred what was commonly known as “alternative country” music.

To be sure, “Country Music” does occasionally note controversies and debates, most commonly in a brief image, video clip, or voiceover. Discussion of Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” (Episode 5, “The Sons and Daughters of America, 1964-1968”), for instance, highlights the many ways that the song could be interpreted, particularly at the height of debates about the Vietnam War and Civil Rights. So, too, does the legendary rift between bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe and former sidemen Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs garner discussion. And singer-songwriter Jeannie Seely’s outspoken criticism of the patriarchal attitudes of country music executives (Episode 5) bears multiple viewings and, in light of recent reporting on women in the country music industry, reveals the depth to which such attitudes and behaviors extend within the industry.

But still more common in “Country Music” are efforts to smooth over these debates, controversies and conflicts— or simply to pretend that they did not happen at all. Such is particularly the case in Episodes 5 and 6, which together cover the period between 1964 and 1972. Here, “Country Music” is quick to point out the resistance that some artists had to Vietnam War protesters, particularly in a steely-eyed interview with singer Jan Howard, who lost two sons as a consequence of the Vietnam War.

As well, the film showcases the work of Earl Scruggs, Charlie Daniels and others to engage with the counterculture and to provide material support for their cause. But conspicuously absent from the narrative is the country music industry’s decided resistance to the Civil Rights Movement, as exemplified by the profound support that many industry leaders and artists offered segregationist George Wallace as early as the 1950s and most notably in his 1968 presidential campaign. Interestingly, this subject is broached on page 375 of the latest edition of Malone’s “Country Music, U.S.A.,” but no mention is made in Burns’ documentary re-telling.

Implicit– and, at times, explicit– in these oversights and smoothings out is whiteness. Whiteness shapes everything in “Country Music,” with white voices— and voices that confirm what white voices have to say— given priority.

Three African American country artists are given a platform to speak: Charley Pride, Rhiannon Giddens and Darius Rucker. Additionally, Wynton Marsalis, who has collaborated with such country artists as Willie Nelson and Del McCoury, appears periodically to emphasize the ways that exchanges between people of color and whites have shaped music-making in the Americas.

Although Pride’s story does detail some of the bigotry that he encountered as he was trying to break into the industry, the other African American speakers are treated as tokens that endorse country music’s presumed whiteness through their presence. Moreover, the film’s treatment of DeFord Bailey, an African American harmonica player who performed on the “Grand Ole Opry” during its first decade, draws attention to his white patrons— including Uncle Dave Macon and the Delmore Brothers— who treated Bailey with dignity while completely decontextualizing his dismissal from the “Opry” at the precise moment that it began to garner national attention.

Similarly, Mexican American country recording artists Johnny Rodriguez and Freddy Fender receive mention, as does famed accordion player Flaco Jiménez, but their presence in the film reads more often as a reinforcement of the genre’s whiteness by pointing to their exceptionalism. As I have written previously, the deliberate construction and reinforcement of country music’s whiteness have led many to believe that the genre cannot be a viable expressive space for artists of color and queer artists.

In presenting a handful of non-white and non-cishet artists as exceptions to country music’s whiteness, Burns’s “Country Music” is not atypical. But, as a country music scholar and a bluegrass musician, I find myself frustrated that the Burns team relied so heavily on well-worn and convenient narratives in the development and presentation of their film.

I wonder what “Country Music” would have looked and sounded like if the voices of Diné musicians in Arizona and New Mexico were included in place of the extended discussion of Johnny Cash’s celebration of Native American themes offered in Burns’s film.

And what about the many African American musicians who were uncredited contributors to early country music recordings, only to be rediscovered through meticulous research nearly a century later?

How might our understanding of the genre’s entrenchment in patriarchal values be changed if we were to consider the many queer communities that have found meaning in country music?

And, as journalist Ludwig Hurtado recently suggested, how might our notions of national belonging change if the story of country music included Mexican and Mexican American audiences who have both contributed to and engaged with country music from the very beginning of the genre?

To be sure, “Country Music” is an enjoyable film, and country music fans will likely revel in seeing the stories of their favorite artists presented in the Ken Burns style. As a lifelong fan, I certainly did. I sang along with the hits, and I wept at some of the more emotional moments.

But I also long for a depiction of country music culture that embraces the debates around the car radio about whether country music has lost its soul, that interrogates the many ways that the genre has been co-opted in the name of patriotism and that considers how people from many walks of life find meaning in the music.

I didn’t get those narratives from Burns. But that’s a “Country Music” I could get behind.