In the spring of 2015, KentuckyWired, the Bluegrass State’s ambitious plan to bring high-speed internet access into rural areas, had ground to a halt.

Officials were in talks with Macquarie Capital, an Australian investment bank known for organizing big infrastructure projects around the globe, to build and manage the new network. But the bank wanted $1.2 billion over three decades — money Kentucky didn’t have on its own.

To make the unique public-private partnership work, then-Gov. Steve Beshear and his administration needed to tap into a federal program that awarded money for broadband projects. And it was a long shot; the Federal Communications Commission had already signaled concern over Kentucky’s eligibility.

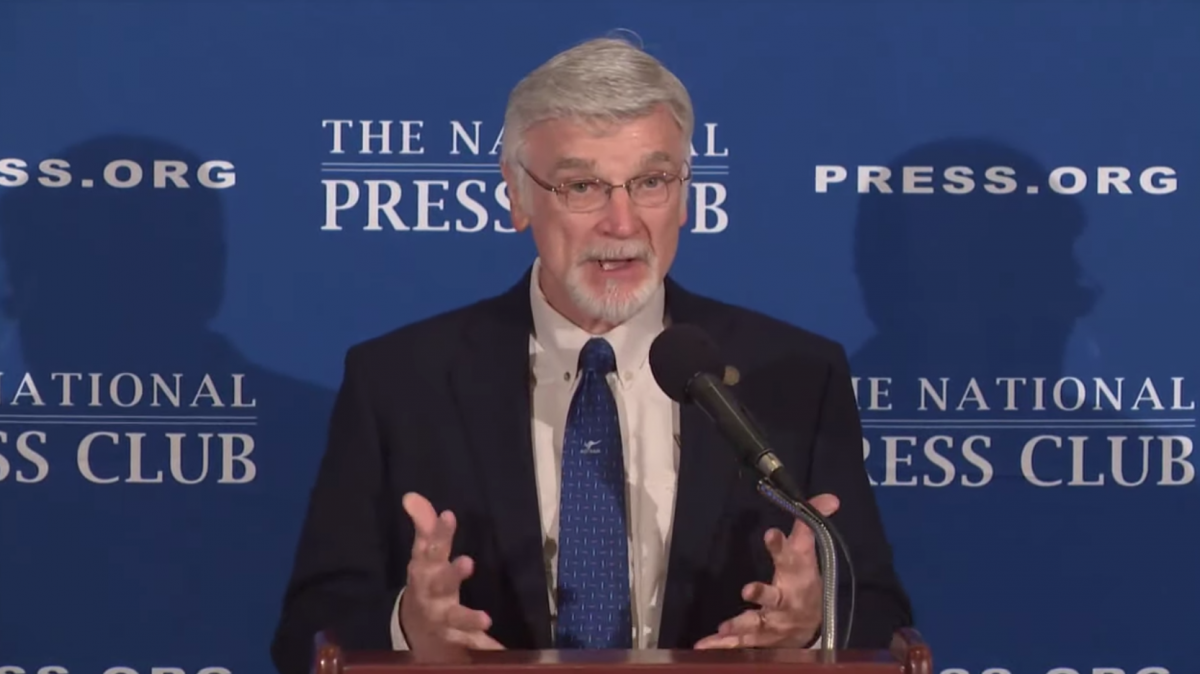

That’s when Macquarie brought in a consultant to help: Frank Lassiter.

The pick was surprising. Neither Lassiter nor his consulting firm, HealthTech Solutions of Frankfort, had any experience in telecommunications or in navigating the FCC’s complex program rules. Lassiter’s own background was in forestry and landscaping; he spent his early career teaching landowners about forest management and later opened a landscaping business named Four Seasons.

But Lassiter had connections. His wife, Mary Lassiter, was Gov. Beshear’s cabinet secretary, the highest appointed position in the executive branch.

Over the next couple of months, Frank Lassiter’s firm reassured state officials that federal support was winnable, coaching them on how to reapply with the FCC to win the millions they needed to make the Macquarie payments. It even produced a report suggesting additional millions were readily available from the federal government to offset construction costs.

Lassiter’s firm was wrong.

By November of that year, scarcely two months after the state signed its deal with Macquarie, the bid for federal aid fell apart, leaving Kentucky taxpayers on the hook for nearly half the $1.2 billion the state now owes the investment bank.

The previously unreported hiring of Lassiter was part of a series of fateful decisions that set KentuckyWired on a disastrous financial path, a joint Courier-Journal and ProPublica investigation has found.

Eager to launch KentuckyWired in the waning days of the Beshear administration, state officials disregarded warnings that they might not qualify for the FCC money and instead attempted to work around federal procurement rules, according to a review of thousands of pages of documents and dozens of interviews.

In the project, Beshear, a Democrat, saw his legacy: economic revival for a poor state, spurred by new access to broadband. Macquarie, headquartered in Sydney, Australia, saw dollars: KentuckyWired could serve as a blueprint for a new line of lucrative business in America.

Today, project leaders say KentuckyWired won’t be completed until October 2020 — two years behind schedule — at a cost that is more than $100 million over budget. The deal is now the subject of an ongoing inquiry from the state auditor’s office, which is examining the “lengthy and unorthodox procurement process” that resulted in the agreement with Macquarie.

Meanwhile, over the past four years, state officials have been forced to make across-the-board budget cuts in the face of skyrocketing pension and Medicaid costs, slicing deeply into higher education.

Macquarie declined to comment for this story. The Lassiters, through their attorney, Guthrie True, have denied any wrongdoing.

He said Frank Lassiter’s consulting firm, which was paid nearly $26,000, lost money on KentuckyWired, resulting in “no financial benefit,” but did not explain how that was the case. And Mary Lassiter, he added, didn’t participate in “any decision-making” related to the consulting firm’s work on KentuckyWired or any other project.

But Mary Lassiter was deeply involved in KentuckyWired discussions. In fact, records show, she ultimately chaired the state authority charged with overseeing the ambitious broadband initiative.

For longtime critics of the project, revelations about Frank Lassiter’s hiring raises new “red flags as to the motivations of the previous administration,” said state Sen. Chris McDaniel, a Republican who chairs the Senate Appropriations and Revenue Committee, the upper chamber’s powerful budget-writing panel.

“It continues to go from bad to worse,” McDaniel told the Courier-Journal before calling for an investigation by the state attorney general, Andy Beshear, a Democrat and the son of the former governor.

Andy Beshear was not involved in KentuckyWired but is himself now running for governor. A spokeswoman for him said, “The Office of the Attorney General has not received any information that would warrant an investigation into this matter.”

A Risky Bet

From the outset, Kentucky’s play for federal funds was risky.

Officials hoped to tap an FCC program known as E-rate, which subsidizes broadband access in public schools. In Kentucky, AT&T provided internet service across state government, receiving $11 million a year from the program. But with KentuckyWired, Steve Beshear’s administration saw an opportunity to compete with — and eventually supplant — the telecommunications giant.

The money, in turn, would cover nearly half the state’s payments to Macquarie each year as state government used the new network.

In February 2015, Mary Lassiter, as secretary of the governor’s executive cabinet, convened a meeting with state education officials to discuss the plan, according to an invitation and emails obtained through a public records request.

Then-Kentucky Commissioner of Education Terry Holliday told Lassiter that KentuckyWired wouldn’t qualify for the federal funds. The FCC’s rules were clear: The state must pick its internet provider based primarily on price, a rule designed to protect federal taxpayers.

But in choosing Macquarie as its partner, the state had weighed other factors more heavily, such as business plan and viability. Holliday declined to comment to the Courier-Journal.

Weeks later, in mid-March, an FCC program official confirmed KentuckyWired wasn’t eligible for the E-rate money, according to records obtained through a public records request.

And yet, state officials pressed forward in talks with Macquarie.

David Couch, the state Education Department’s tech chief, recalled later to the state auditor’s office that project leaders “somehow got the impression that they had the power, influence, connections, backing and/or ability to bluntly force to be done what they wanted done,” including overriding federal regulations.

Couch declined requests for comment.

A New Consultant, a New Path

In spring 2015, as negotiations with the state stalled, Macquarie hired Frank Lassiter.

According to its website, Lassiter’s firm, HealthTech, typically focuses on health care with its clients. The company had no previous experience in procuring E-rate funds, Lassiter’s lawyer confirmed to the Courier-Journal.

Nevertheless, Frank Lassiter had been corresponding regularly with state technology officials about the program for months, according to emails the newspaper obtained.

The Lassiters’ attorney said in an email that it’s normal for companies to “explore business opportunities that may not be directly related to their core business.” And KentuckyWired, which is designed to serve all state government agencies, was “expected to have a significant component related to healthcare.”

Local health departments are expected to be part of the new network, but they are small in comparison to Kentucky public schools.

In addition to its consulting fee, the firm saw an opportunity to make much more by helping to sell the new network’s excess broadband capacity to private-sector customers, something Macquarie estimated would generate nearly $2 billion in revenue over 30 years.

To make up for its lack of expertise, HealthTech hired another consultant named Joe Freddoso, the former head of a North Carolina broadband network similar to KentuckyWired. He dangled the possibility that KentuckyWired could “recover a significant percentage” of the new network’s construction costs by taking advantage of a recent change to FCC rules.

Freddoso was in a strong position to know. At the time, the consultant was also working as a researcher for the FCC program.

Together, Lassiter and Freddoso charted a new path to win federal funds, records show. A HealthTech memo obtained by the Courier-Journal explained the strategy. Instead of replacing AT&T as the state’s internet provider in one shot, the state would take a more surgical approach and seek to win a broadband contract for public schools.

And this time, the state would follow the federal government’s strict procurement rules.

The plan still tested those restrictions; as it stood, Kentucky and its private-sector partner, Macquarie, would be both the applicant and the service provider, typically a violation of regulations.

Guided by HealthTech, the state set up bureaucratic firewalls to appease the federal agency. A new state authority would be created to oversee KentuckyWired, so that when the state asked for new bids for school internet service, this ostensibly independent entity — the Kentucky Communications Network Authority — rather than Macquarie would be making a case to replace AT&T.

Friends in High Places

As secretary of Beshear’s executive cabinet, Mary Lassiter was aware that having her husband consult on a major state project could pose at least the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Years before, Lassiter promised Beshear she would abstain from involvement in matters related to her husband’s employment, including his nursery, which had previously won a state contract with the forestry division.

And in a subsequent update in 2013, she added HealthTech to the roster of potential conflicts. She said that it was “highly unlikely that an actual or potential conflict would arise related to Frank’s business interests” because she did not oversee awarding contracts.

But if her husband were to work on a state project, Mary Lassiter nevertheless pledged to “abstain from any involvement whatsoever in the process.” She would also notify the governor immediately of her husband’s hiring.

KentuckyWired would put both of those promises to the test.

The Lassiters’ attorney said Mary Lassiter avoided potential conflicts because she did not “participate in any decision-making” related to her husband’s firm on KentuckyWired or any other project.

But in the months leading up to the 2015 negotiations, Mary Lassiter provided the governor updates on an eastern Kentucky economic development group that hatched the idea for KentuckyWired, according to cabinet meeting agendas. And, as the talks with Macquarie progressed, she convened the meeting to discuss the Education Department’s role in the new network.

For its part, HealthTech appeared to prefer working behind the scenes, offering “very confidential” suggestions for nudging the FCC and saying in [a May 2015 memo that it would “help communicate between the parties,” but that its employees would “recuse themselves from any formal meetings.”

It’s unclear whether Mary Lassiter told Beshear about HealthTech’s role in KentuckyWired. Neither the Lassiters’ attorney nor Beshear responded to requests for comment on the matter.

A Different Kind of Conflict

Reassured by HealthTech that they could win the FCC money, state officials tried again.

Wall Street was aflutter with anticipation as the state would soon be selling bonds to support the project. In August 2015, the rating agency Fitch told potential investors in KentuckyWired bonds that the project would serve as the “primary means of internet and network access” for K-12 schools, an important piece of the network.

Eric Kim, the Fitch analyst responsible for covering Kentucky, says that detail was “repeated several times” in discussions with both state officials and Macquarie team members.

But, as the state prepared to open bids for school internet service, the Kentucky Department of Education again raised concerns, this time about what it described as a potential conflict of interest.

Some of the same state officials writing the request for bids were also in contact with Macquarie, the firm that would be bidding on it, warned Couch, the department’s head of technology, in an Aug. 27 email to the state finance official leading the effort. He cited the FCC’s rule against such behavior.

“This best practice helps avoid a real or perceived impression that a certain vendor got a certain edge,” Couch said.

The potential conflict of interest, however, went deeper. In crafting the new request for bids, state officials were relying heavily on the advice of an FCC contractor — Joe Freddoso. The former HealthTech consultant, who had helped Macquarie and the state devise its E-rate strategy months earlier, had changed roles again and was now working for the agency administering the program, advising states on how to navigate its requirements.

It’s unclear whether federal rules allowed that. Freddoso said he received special permission to work on KentuckyWired. A spokesman for the FCC arm that administers the E-rate program and its lawyer declined to comment.

Either way, Couch complained to his bosses that Freddoso had offered a flawed analysis of broadband prices by repeatedly arguing that Kentucky was “being gouged” by its current provider. The state, Couch later wrote, may “already have the very best prices” from AT&T. He pushed finance officials to deal directly with the FCC.

The administration did not heed the warnings. On Sept. 1, 2015, in a departure from normal protocol, Don Speer, Beshear’s head of procurement services, emailed Couch to say his office was taking over the solicitation.

Speer did not respond to a request for comment.

Two days later, the state finalized its deal with Macquarie.

At a celebration marking the project’s launch, KentuckyWired supporters billed it as the “most historic construction project in our lifetimes.” And state Senate President Robert Stivers singled out Mary Lassiter as a critical contributor who “really kind of made the thing move.”

On Sept. 4, 2015, Mary Lassiter chaired the first meeting of the board of the newly created Kentucky Communications Network Authority.

A month later, in a unanimous vote, Lassiter and her colleagues greenlighted KentuckyWired to submit a bid for school internet service, according to minutes the Courier-Journal obtained through a public records request.

On Nov. 3, 2015, voters picked Republican Matt Bevin in an upset to succeed the term-limited Beshear as governor. Three days later, AT&T filed a complaint regarding the state’s bidding process. The company alleged the state had “stacked the deck” against it and “preordained” that KentuckyWired would win.

AT&T called for “this web of conflicts of interest” to be dissolved and for the state network to be barred from bidding. Weeks later, the state dropped its plans to award a new contract, meaning KentuckyWired would not be eligible for the FCC money.

Beshear’s finance secretary, Lori Flanery, later told the state auditor’s office she halted the E-rate effort so that the broader project could proceed without the delay of a dispute. She said she was not aware of the federal money’s importance, “despite finance officials leading the KentuckyWired effort throughout 2014 and 2015,” investigators wrote in their initial report last year.

“What happened now is different than what we anticipated, certainly,” said Fitch’s Kim, adding that the agency’s relatively high BBB+ rating of KentuckyWired bonds nevertheless hasn’t budged because the state is contractually obligated to make payments to Macquarie.

The Fallout Continues

Now, taxpayers are on the hook.

The state auditor’s office told the Courier-Journal it’s continuing to investigate KentuckyWired. In September 2018, it referred its initial findings to Kentucky’s Executive Branch Ethics Commission. According to Kentucky law, if the commission finds a violation of the code, including conflicts of interest when awarding state contracts, the state’s finance secretary may void any agreement related to that case.

Bevin, a onetime critic who now supports completing KentuckyWired, has also launched an investigation into what his office called the potentially “unsavory and perhaps illegal practices” of his predecessor’s administration. That includes another deal involving the Lassiters — a $3.1 million no-bid contract that Frank helped a software company win on the last day of Beshear’s tenure.

This article was produced in partnership with the Louisville Courier-Journal, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. It was originally published by ProPublica.

This story is part of an ongoing investigation into what went wrong with KentuckyWired. Sign up for the Miswired newsletter to receive updates in this series as soon as they publish.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.