Collective bargaining has long been one of organized labor’s most attractive selling points.

In its simplest form, collective bargaining involves an organized body of employees negotiating wages and other conditions of employment. In other words, unions are saying: Join us, and we’ll bargain with your boss for better pay.

Unfortunately, traditional collective bargaining is no longer an effective strategy for labor union growth. That’s because employers and many states have made it incredibly hard for workers to form a union, which is necessary for workers to bargain collectively.

My own research suggests unions should pursue alternative ways to organize, such as by focusing on more forceful worker advocacy and offering benefits like health care. Doing so would help unions swell in size, putting them in a stronger position to secure and defend the collective bargaining rights that helped build America’s middle class.

Why unions still matter

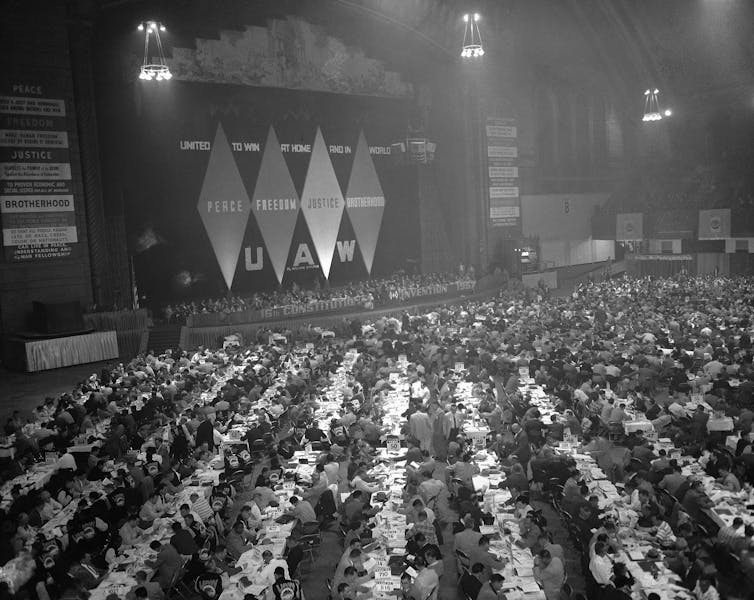

Unions reached their pinnacle in the mid-1950s when a third of American workers belonged to one. Today, that figure stands at just 10.5 percent.

A big part of the problem is that employers have used heavy-handed legal and managerial tactics to block organizing and the elections necessary to form a union. And more than half of U.S. states have passed so-called right to work laws, which allow workers at a unionized company to avoid paying dues.

The stakes of this challenge are high – not just for unions but for most workers in the U.S. That’s because weaker unions correlate with lower wages, reduced benefits and greater economic inequality.

Millions stand to gain from a strengthened labor movement, from Uber and Lyft drivers in the gig economy to low-wage employees in retail and hospitality. And surveys show nearly half of nonunion workers in the U.S. say they would join one if they could.

I believe there are three models traditional unions could pursue to add members without relying on workplace certification and collective bargaining.

Advocating for workers

One approach is to build on the success of worker advocacy groups like Fight for $15 and the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

Fight for $15, for example, played a leading role advocating increases in the minimum wage in several states, most recently Connecticut, while the National Domestic Workers Alliance helped secure the passage of the domestic workers bill of rights in New York.

What they all have in common is that they engage in protests and strikes to call public attention to the plight of exploited workers while advocating for economic and social justice. Unions, which used to engage in more of this kind of activism, need to recapture some of that militant spirit.

Establishing minimum standards

A second model involves pushing employers to agree to a minimum set of standards for benefits and pay to provide workers.

The Writers Guild of America, which represent screenwriters and others in television, theater and Hollywood, exemplify this model. For example, they establish minimum levels of compensation for specific jobs and duties and then require members – both employers and workers – to adhere to them. It’s a collective bargaining agreement with a potentially much wider reach.

That’s because these agreements are negotiated with employers but also cover independent contractors who sign on as well. Their strength comes from the aggressive organizing and advocacy plus the strategic importance of the workers they represent, which puts pressure on employers to take part and meet the minimum standards.

Other unions could expand this approach to encourage workers throughout industries that have little or no labor representation to join their ranks as affiliated members, which should pressure employers to follow suit.

Unions with benefits

Another approach involves focusing on offering special benefits to independent workers in exchange for fees.

Some labor groups already do this, but the workers would benefit from unions combining their collective power to offer more heavily discounted goods and services, such as health care, disability benefits and legal representation.

For example, although the 375,000-strong Freelancers Union can’t negotiate over pay, it offers independent contractors these sorts of discounted benefits. Instead of charging dues, it charges fees for its benefits, essentially operating as its own insurance company. It also advocates for public policy changes that safeguard freelancers from exploitation, such as New York’s Freelance Wage Protection Act of 2010.

This model is probably the approach most likely to succeed in attracting large numbers of new members. The growing gig economy and low-wage industries like fast food are two areas that could receive benefits from these types of collective entities.

The endgame

Ideally, unions would embrace all three of these models, offering discounted benefits to any worker interested in signing on, fighting for minimum standards across industries and putting worker advocacy front and center. By broadening the ways in which workers can join and what they offer, unions will become stronger and closer to the people and communities that they are meant to represent.

But by no means are these models meant to supplant organized labor’s traditional collective bargaining role. My point is that unions should break the straightjacket fixation on traditional bargaining and use alternative models as intermediate steps to the ultimate goal of unionizing more workplaces in order to negotiate collective bargaining agreements on behalf of workers.

To get there, though, unions must mobilize a critical mass of workers. Only then will they break the dynamic of labor’s decline.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

Marick Masters, Professor of Business and Adjunct Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.