Financial insecurity is a common struggle for families in Homewood, a predominantly African-American neighborhood on Pittsburgh’s East End. Although it was difficult at times, Khaynin Mosley-Smith said his family was able to make ends meet.

“I didn’t struggle extremely bad, but financially it wasn’t all the way there. My mother held up her end. I have seven brothers and sisters, and it was just her and my grandmother,” Mosley-Smith said.

In a neighborhood ravaged by poverty, crime and urban blight, many adolescents leaned on sports to stay off the streets, Mosley-Smith recalled. Like other kids, Mosley-Smith said he spent much of his time playing sports like baseball and football.

Realizing his talent, particularly in football, his mother eventually moved the family to nearby Swissvale so her son could attend the suburban Woodland Hills High School and have a shot at a scholarship.

A senior season with 61 tackles and seven sacks sealed the deal, eventually earning Mosley-Smith a scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh. This scholarship, Mosley-Smith said, was opportunity to change his family’s life.

“That’s what we all strive for as student-athletes, especially the less fortunate. Because when you’re in the locker room, you see guy’s lives changing every year who are entering the draft,” the defensive tackle and first-generation college student said.

But even with a full ride to Pitt, Mosley-Smith said he still faced significant financial difficulties. While his athletic scholarships came in the form of monthly checks he and his teammates could use however they wanted, it was difficult to make the money last an entire month after paying for housing.

“There’d be days when one of us would just be like, ‘hey, I’m going to grab some stuff off the dollar menu, and we would just eat that all day,’” Cameron Saddler, a former teammate of Mosley-Smith’s, recalled.

Those who didn’t have the luxury of calling home and asking for money, Saddler said, struggled the most. Median household incomes in Mosely-Smith’s Homewood, for example, are little more than $20,000 per year. The federal poverty level for a household of three is $21,330.

The struggles faced by athletes like Mosley-Smith and Saddler are not unique, according to Fritz Polite, president of The Drake Group, housed in the business school at the University of New Haven, which advocates for student compensation for the use of their likenesses and images, among other things.

“Those are cases that the [National Collegiate Athletic Association] completely ignores and takes that kid and utilizes them to their fullest,” Polite said.

A 2011 study from the National College Players Association, which also advocates for pay for college players, found 86 percent of student athletes who live off campus, and 85 percent who live on campus, live in poverty. But the study valued the average college football player at $121,048 and the average basketball player at $265,027.

In 2017, college athletics programs in the U.S. generated $14.1 billion in revenue, according to the U.S. Department of Education, up from $4 billion in 2003.

But that profit doesn’t trickle down to the students themselves. And for those that do struggle financially, routine practices, conditioning workouts and team meetings take up a majority of their time.

“These guys are doing 50 to 60 hours,” Polite said, after factoring in weekly requirements like film sessions, transportation and game-day activities.

“Besides playing the games, they also must practice, endure training and conditioning, and also attend meetings. Because of this, any kind of employment is virtually out of the question,” said Keith Anderson, an entrepreneur based in Bluefield, West Virginia.

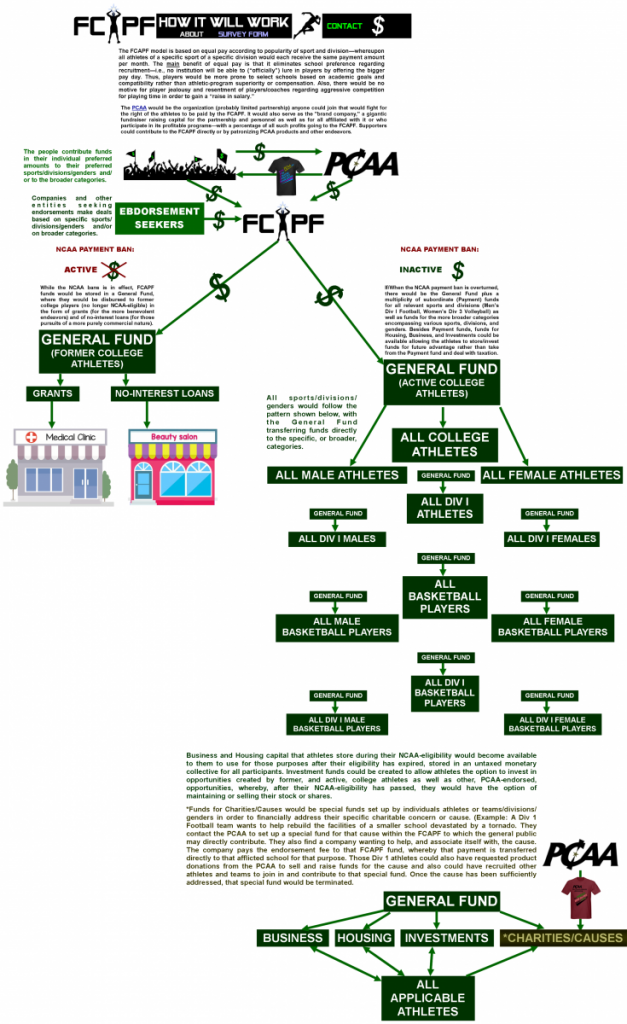

Anderson recently founded the Pay College Athletes Association. In his model, fans would donate to the PCAA and could designate which divisions and sports receive their money ̶ almost like a Kickstarter campaign, but for collegiate sports. Donors, for example, could choose to support Division I football or Division II women’s volleyball and essentially pay their favorite athletes.

Recipients of the funding have the flexibility to use the donations any way they want, just as if they were being paid to play. Any athlete receiving funds while in school would have extra money to spend, save, or invest. Or they could choose to send the money back home if their families need it, Anderson said.

“There are those living in a substandard status who could benefit from that extra cash to help pay regular bills or subsidize higher education for siblings or other family members,” he said of the economic benefits for families.

But as it stands, no student athlete can accept a third-party payment without NCAA approval. Although a federal judge ruled earlier this year that colleges and universities can remove NCAA caps on academic awards to student athletes, it left intact the organization’s amateur structure, barring payment. Anderson has a plan for getting around this roadblock: a petition.

“All during its development, the PCAA will continually gather support from the people to petition the [NCAA] to lift its ban. When enough support is gathered, the PCAA will approach the NCAA with a profit-share deal,” he explained.

As a former college player, Saddler thinks the third-party payment could undermine the fundamental purpose of the NCAA and introduce confusing incentives for players. Receiving a paycheck from outside of the university, while being encouraged to go to class by the NCAA, can create conflicting incentives, he said.

Saddler also doubts Anderson’s ability to truly raise funds, even from the most loyal fans who are already purchasing game tickets, apparel and participate in fundraising events. A payment system would be nice, Saddler said, but schools don’t need more money in order to pay the student athletes.

“They have the money, they have the funds from the tickets and the jersey sales, it’s there,” he said.

Instead, he’d like to see the NCAA loosen its rules that prevent athletes from earning money off of their likenesses on those jerseys, game tickets and even video games. A federal court did rule in 2014 that the NCAA violated anti-trust law by restricting payment for commercial use of athletes’ images, names and likenesses, although the March decision only reaffirmed that the NCAA can restrict payments that are not educational in nature.

But it’s not just the financial struggle that so many student athletes face while they’re still in school. Athletes also face a strain on their academics that results in additional challenges after graduation.

“They let you know the majors that kind of make it easy to finish your degree, and you can kind of get by with football,” Saddler said.

That’s why Polite and the Drake Group have named academic integrity among their top priorities, lobbying for policies that “ensure the primacy of academic study.” Polite explained there is a difference between a degree and an education. A degree alone does not give a student critical thinking or effective communication skills, for example, skills that help the average college graduate stand out in the workforce.

“The fact that you can go to school, you can wear a backpack and go to practice is not fully helping [athletes] financially,” he said.

Anderson doesn’t limit his model to just aiding current student athletes. The money donated to his Pay College Athletes Association could be used to offer grants and no-interest loans to former athletes as well. Athletes could benefit from access to extra capital, perhaps to start a business, he said. Grants or no-interest loans could also go to athletes who want to further their education.

“It could be considered ‘economic justice’ for not getting paid for their services while in school,” Anderson said.

Until the NCAA lifts its payment ban, all PCAA money would go toward funding former athletes. Anderson said he wants to give priority to athletes who want to start businesses in low-income communities.

That aid, especially if combined with guidance, could help collegiate athletes who don’t make it to the next level, said Saddler, who graduated in 2013 with a degree in communications.

“When I first graduated, just figuring out what the next step was going to be … it kind of took some time, because my whole life, I was playing sports,” Saddler said.

Although it took him a few years to navigate life after football, Saddler has spent the past four years working with youth, teaching physical education and leadership at Nazareth Prep, a Catholic high school in Emsworth, Pennsylvania. This past spring, he helped lead a project that explored the struggles people who are homeless face trying to get back on their feet. He couldn’t help but point out one striking similarity to the struggles faced by former student athletes.

“You’re starting from scratch, you’re not sure where you’re going,” Saddler said. “We all have these degrees and it’s just like we don’t know where to go.”

Anderson didn’t say that his work with PCAA can solve every problem athletes like Saddler face. But he hopes it can offer some additional benefits to athletes, given the value they provide to their schools.

“College athletes generate millions for college coaches and billions for everyone else–including amassing great publicity for the schools they represent,” he said. “The athletes deserve a piece of the pie in exchange for the benefits they provide.”

Sam Bojarski is a freelance journalist based in Pittsburgh. He covers local news in the Steel City and the North American maritime industry for national trade publications. He also contributes to the Haitian Times, the leading Haitian diaspora publication in the United States.