A Trump administration proposal calls for increasing Medicare reimbursements for some rural hospitals by taking money from hospitals in major urban areas. Both opponents and proponents of the measure say the entire Medicare reimbursement system needs an overhaul.

While proposed changes to Medicare reimbursements to hospitals may keep some rural hospitals from closing, industry executives say the entire system of reimbursement needs to be reformulated.

A proposal by the Trump administration would raise reimbursement rates for some rural hospitals by taking the money from reimbursements to the richest hospitals. Advocates for rural hospitals say it is a way to save those hospitals from closing. But hospital advocates in urban areas say their hospitals shouldn’t be penalized to help those in poorer communities. Still, others say the way reimbursements are determined is flawed.

For some rural hospitals, the proposal could be a game-changer. But about half of all rural hospitals won’t be affected by the changes.

Currently, Medicare reimbursement for hospitals is determined by the U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) using the “area wage index,” which adjusts a hospital’s reimbursement rate based on how much the hospital pays its staff. Hospitals report their wages to the CMS, where they are compared to wages in their respective labor markets. The index is intended to create an annually updated measure that shows how hospital wages compare across regions.

Under this method, hospitals located where wages are lower than the national average receive lower reimbursement rates than those in areas where wages are higher than the national average. Research from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that the median wage index for urban hospitals is substantially higher than the median wage index for rural hospitals, regardless of the hospital’s size.

According to the CMS, the system perpetuates an already existing inequity.

“High wage index hospitals, by virtue of higher Medicare payments, can afford to pay their staff more, allowing the hospitals to continue operating as high wage index hospitals,” CMS said in a statement. “Conversely, low wage index hospitals often cannot afford to pay wages that would allow them to climb to a higher wage index. Over time, this creates a downward spiral that increases the disparity in payments between high wage index hospitals and low wage index hospitals, and payment for rural hospitals and other low wage index hospitals declines.”

Proposed Changes

To address this, in April CMS Director Seema Verma proposed changing the system to increase reimbursements for hospitals near the bottom of the area wage index and to reduce reimbursements for those near the top of the wage index. (Under the proposal, hospitals in the bottom 25 percent of the wage index would increase by half the difference between their wage index value and the national 25th percentile wage index value. Hospitals in the top 25 percent of the wage index would receive lower reimbursements, which would keep the changes from raising the overall cost of the program.)

Verma called the policy a rethinking of rural healthcare.

“One in five Americans are living in rural areas and the hospitals that serve them are the backbone of our nation’s healthcare system,” Verma said. “Rural Americans face many obstacles as the result of our fragmented healthcare system, including living in communities with disproportionately higher poverty rates, more chronic conditions and more uninsured or underinsured individuals.”

The difference could mean thousands of dollars per patient for rural hospitals.

For example, under the current reimbursement system, a hospital in a rural community might receive a payment of $4,000 for treating a patient for pneumonia, according to CMS. But at a hospital in an urban community with a higher wage index, the same treatment might be reimbursed at a rate of $6,000.

Still, those payments are well below what hospitals must spend to treat patients. According to a study by the AHA in 2015, Medicare and Medicare reimbursements to hospitals were $57.8 billion less than what it costs the hospitals to provide services.

The study found that Medicare reimbursements amounted to an estimated 88 cents for every dollar spent by the hospitals.

“Payment rates for Medicare and Medicaid, with the exception of managed care plans, are set by law rather than through a negotiation process, as with private insurers,” the study found. “These payment rates are currently set below the costs of providing care, resulting in underpayment.”

Something Is Better Than Nothing for Many

For some hospitals, the money they get from Medicare may be pennies on the dollar but may still generate substantial revenue for the healthcare organization. And the consequences of not having that federal funding can be dire.

The Pineville Community Hospital Association (PCHA) in Pineville, Kentucky, filed for bankruptcy in November 2018. As part of that filing, Jon Gay, with Lexington-based law firm Walther, Gay & Mack, an attorney for the bankruptcy trustee, said an estimated 90 percent of the hospital’s patients were Medicare or Medicaid recipients. In June 2019, according to bankruptcy records, a deal was reached to have personal property, certificates of needs and other licenses transferred to a non-profit organization, Pineville Community Health Center (PCHC), which took over hospital operations.

The city of Pineville stepped in to help the hospital, loaning PCHC $300,000 to ensure the hospital stays open. For residents in the Pineville area, the closure would mean traveling to the next nearest hospital more than 15 miles away.

Prior to that June agreement, however, CMS had terminated its agreements with PCHA after an investigation found several lapses in patient care, meaning no payments would be made for any future Medicare or Medicaid patients to the hospital. While PCHC is working with CMS to obtain a new provider agreement, the loss of federal revenue to the hospital forced the facility to lay off half of its staff — an estimated 60 people.

“Without Medicare (and) Medicaid, we can’t operate because 75 percent of our revenue is generated through Medicare and Medicaid,” Pineville Mayor Scott Madon told WYMT TV in a June 3 interview.

Pineville, the county seat of Bell County, had a population of 1,732 in the 2010 census. Bell County’s unemployment rate has remained relatively stable, sitting at 5.8 percent as of February 2019. But, according to numbers from the Kentucky Center for Statistics within the Kentucky Department of Education and Workforce, the county’s total workforce in February was 8,448 people. A difference of just 60 unemployed residents would raise the county’s unemployment rate to 6.5 percent. As one of the largest employers in the county, if the hospital were to close, creating the loss of another 60 jobs, the county’s unemployment rate would jump to 7.2 percent, one of the top 10 highest unemployment rates in the state.

Craig Becker, president and CEO of the Tennessee Hospital Association, said the changes to the Medicare reimbursement rates could reshape his state’s healthcare system.

The proposed changes would allow Tennessee hospitals, especially those in East and rural Tennessee, to keep healthcare professionals on staff, as well as help hospitals continue to provide services to their communities, he said.

“Because of the broken Medicare formula, hospitals in Tennessee have lost more than $300 million in Medicare reimbursement in the last 10 years. That money could have been applied to technology, higher wages, recruitment efforts, purchasing of medical equipment and updating many of our aging facilities,” he said in an editorial in the Tennessean.

The issue is particularly important for those in rural Tennessee, he said, where 10 rural hospitals have closed in recent years. Becker said one reason for their closures, among the many, was the area wage index and declining reimbursements.

A Flawed System

Nationally, however, many feel that taking from urban hospitals to give to rural hospitals isn’t an answer to the funding crisis. American Hospital Association Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said another solution needs to be found.

“The area wage index is intended to recognize differences in resource use across types and location of hospitals. Hospitals, Congress and Medicare officials have repeatedly expressed concern that the wage index is flawed in many respects,” Nickels said in an emailed statement. “The AHA appreciates CMS’s recognition of the wage index’s shortcomings. At the same time, improving wage index values for some hospitals – while much needed – by cutting payments to other hospitals, particularly when Medicare already pays far less than the cost of care, is problematic. CMS has the ability to provide needed relief to low-wage areas without penalizing high-wage areas.”

In fact, a study by the U.S. Office of Inspector General entitled “Significant Vulnerabilities Exist in the Hospital Wage Index System for Medicare Payments” found that the Medicare reimbursement system is flawed. CMS lacks the ability to penalize hospitals that submit inaccurate or incomplete wage data and has little oversight to ensure hospitals submit accurate data, the report said.

The Inspector General’s report found that these vulnerabilities might prevent the CMS from accurately determining local wages, which would, in turn, affect Medicare payments to hospitals.

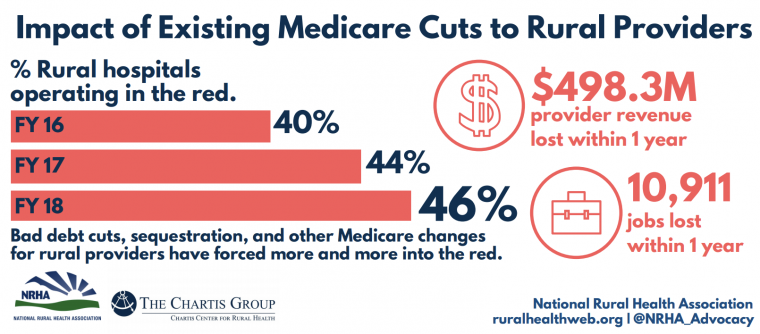

But that doesn’t begin to cover how flawed the system is, said Alan Morgan, CEO for the National Rural Hospital Association in Washington, D. C.

The proposed changes won’t address the needs of nearly half the rural hospitals in the country, those considered critical access hospitals, he said. Critical access hospitals, generally speaking, are those with fewer than 25 inpatient beds in rural areas. For those 1,300 rural hospitals, which are not dependent upon the wage index, the administration’s proposal would have no effect.

“Is this (proposal) a good thing? Yes,” Morgan said. “Is this going to address some payment inequities? Yes. Is this going to solve all the problems faced by rural hospitals? No. It’s a good provision. It’s a targeted provision. But it won’t help almost half of the rural hospitals in our country.”

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.