“We can concern ourselves with presence rather than with phantom, image rather than with conjure. Bad as it is, the world is potentially full of good photographs. But to be good, photographs have to be full of the world.” — Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon, Photographing the Familiar: A Statement of Position, Aperture, 1952.

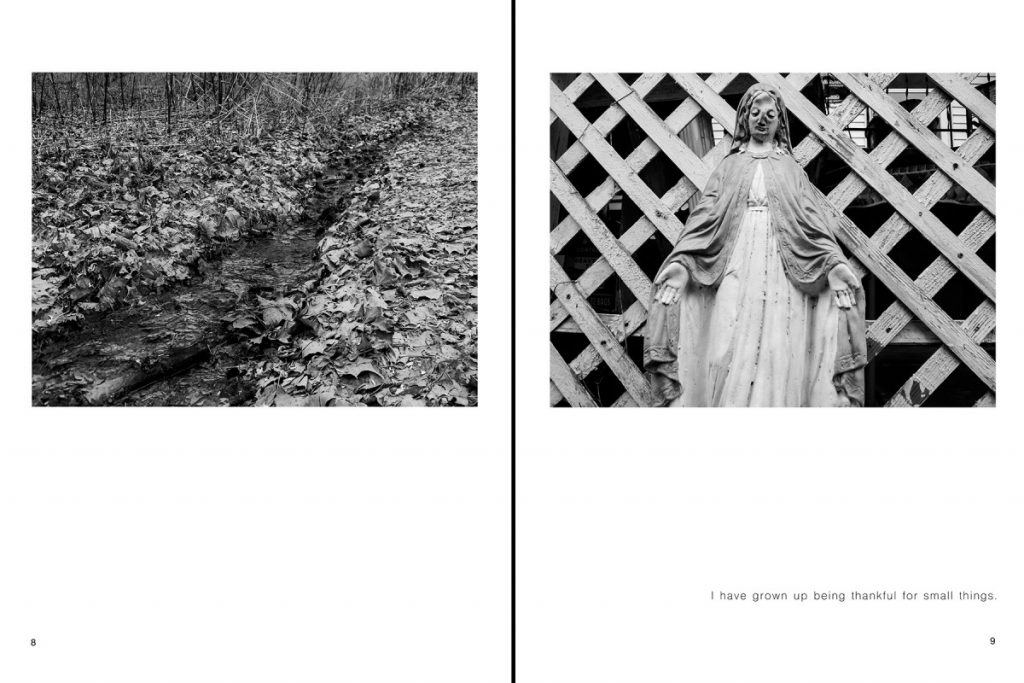

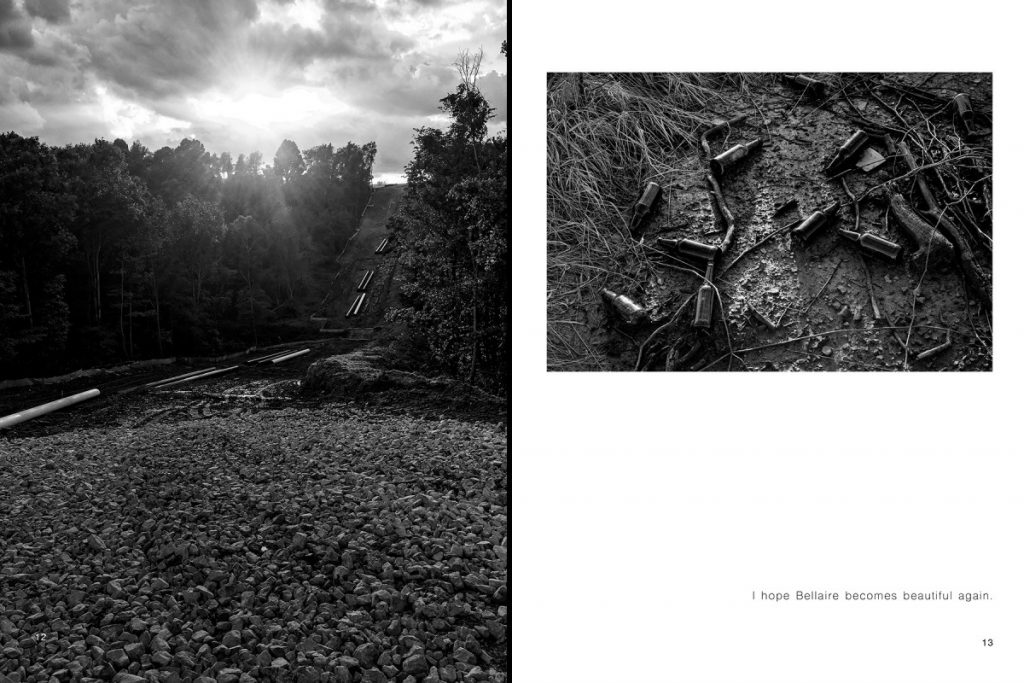

The closing statement of The All-American Town: A Photography Project by The Rural Arts Collaborative, Bellaire High School, a 60-page photobook (some may call it a zine), reads: “These photographs and statements are a sharing of our collective truth and imagination.” And it is striking.

I spend a good deal of time looking at photobooks. For me, it’s important that photographs make their way to print and become something other than pixels stored on hard drives or posts on social media. To be intentional about printing photographs and then structuring those pictures into something that makes sense, that pulls a viewer in, that begs the viewer to return over and over again is not necessarily an easy thing to do.

I first learned of the project, led by Wheeling, West Virginia-based photographer Rebecca Kiger, on Instagram some time before Christmas last year. I had no idea the images I would see unfold in their feed would result in such a thoughtful and beautifully produced photobook.

Despite Kiger’s proximity to Bellaire, Ohio, she was well aware that her presence would be that of an outsider. It took her months to establish trust with her students, which anyone who has worked with teenagers can attest to, and rightfully so. Some were resistant right up to the end. During the year-long project, Kiger developed a rapport with the students.

“My motivation with this project is to let them know their voices matter, their lives matter,” she told me on a call last week. “I feel the length of the program was important because it allowed for the development of trusts and knowing and forming relationships. This is an essential part to creating photography with depth and hopefully healing wounds,” she added.

“Art is the first thing to get cut,” Kiger noted referring to shrinking budgets in schools. So, it was with funding provided by the Benedum Foundation, the EQT Foundation and Oglebay Institute, the Rural Arts Collaborative was able to produce the work and ultimately the photobook in an edition of 500 copies.

Lindsay Hess, a student in the project, wanted to take a photography class, but had no idea of where the class would lead. “It was difficult in the beginning. We don’t really open up that easily to outsiders. Once we realized Rebecca’s idea was great, we opened up and showed her what was around here,” she said. “She (Kiger) really helped open our eyes to what was around.”

When asked about what she hoped others might take from the project, Hess said, “I kind of hoped that it would change people’s stereotypes of the area. For me, I tried showing that we have really good roots and that we still have beautiful surroundings.”

“It’s not just drugs and all the horrible things. It’s not a lazy, dusty old town that people might think it is. There are still good things in this place,” she added.

Judy Walgren, a Pulitzer prize-winning photographer and professor of Practice, Photojournalism and New Media at Michigan State University, served as the photobook’s editor.

“This body of work was like a dream come true,” Walgren shared with me. “For me to be able to be part of it, because I’m an outsider, is a huge honor. The project speaks of Rebecca’s ability to motivate people and, in turn, their ability to turn this into a work. Every student has at least one photo in this book. That’s really uncommon.”

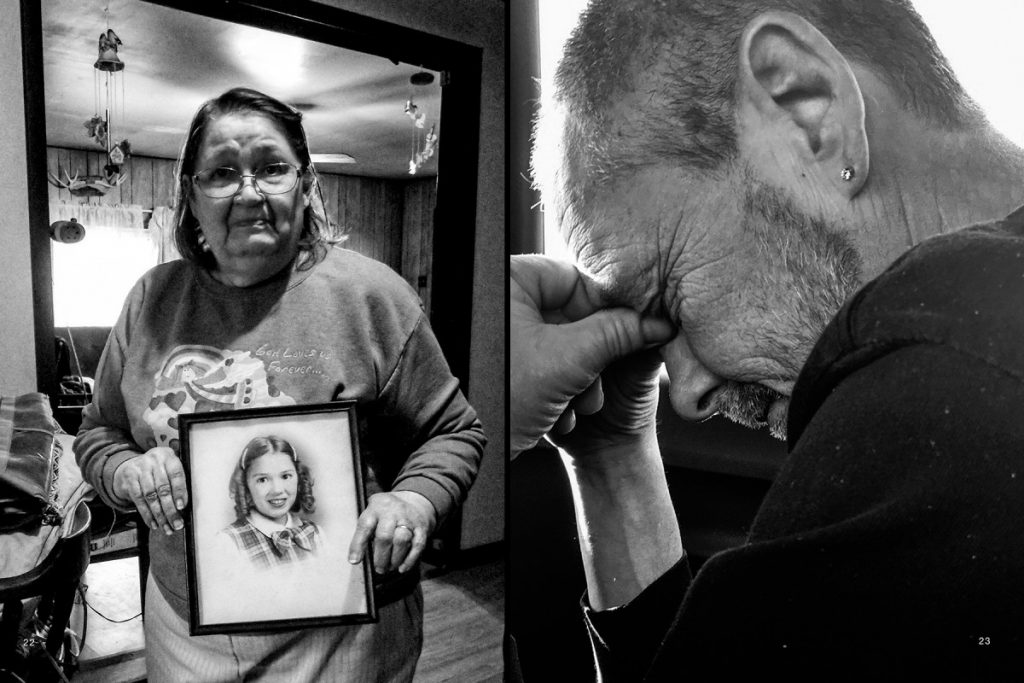

Kiger has worked with Walgren for years on various collaborations. With no background or concept of the project, Kiger asked her to look over a large batch of images and edit them down to a reasonable number. “As I started looking them over, she started telling me more about the project. I had a really hard time narrowing the edit down. I could feel the weight of these lives and shared experiences,” Walgren said.

Walgren’s words resonated with me because I’m guilty of sometimes not being a good listener when it comes to teenagers. More than once I’ve been humbled by the vulnerability and depth of my own children at times in their lives when most adults were quick to dismiss them, let alone give weight to their thoughts or opinions.

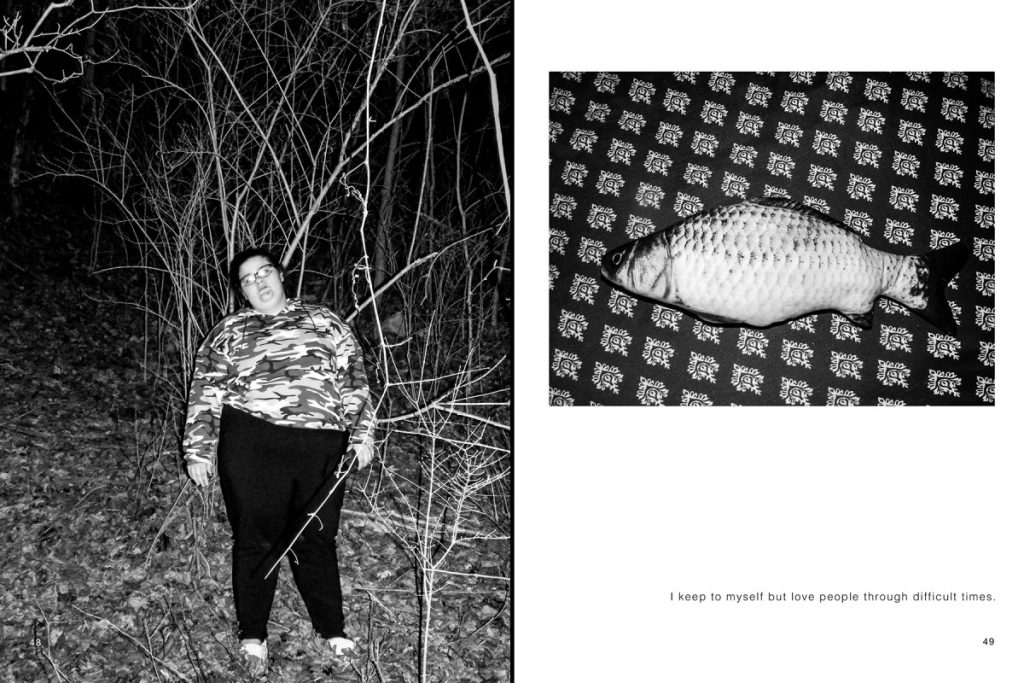

For me, the pictures are decoded fragments that show me something familiar. They speak to me in a way that means something I can identify with despite knowing very little about the place. You’ll find no pretense in the pictures, but rather little windows in which we are all invited to look at not only a place, but at ourselves. These are intimate pictures that seem as if in their making and in our viewing, the photographers move about freely in their world, in their community in a way photographers “not from here” have tried to do since the first camera was deployed in search of other places. They show us what we can’t see but what we can certainly identify with and relate to.

Throughout the photobook, statements from the students are mixed in with the photographs.

“I have grown up being thankful for small things.”

“I used to let my anxiety control me.”

“I am good at keeping secrets.”

“I am afraid of the dark.”

“I’ve had to learn that you can’t trust anybody, not even your parents.”

“I will save others before myself.”

In light of two recent school shootings– STEM School Highlands Ranch in Colorado and the University of North Carolina Charlotte–where students were seemingly the first and last lines of defense and attacked the gunmen head on, ultimately saving lives, this statement is especially poignant. But each felt like a punch in the gut.

“The finished book affirms the risks they took in sharing their lives. The fact that they took those risks, and were vulnerable, makes me very proud of them,” Kiger said. “Even though the subject matter is hard and sometimes dark, it showed them that sometimes opening up like that and sharing is what really reaches people.”

The All-American Town is available for purchase here. Follow the Rural Arts Collaborative on Instagram at @ruralartscollaborative. Follow Rebecca Kiger on Instagram at @rebecca_kiger.

Author’s Note: I received a complimentary review copy of The All-American Town.