In my small town, not all of us believe the same thing. But that doesn’t stop us from believing in each other.

Growing up in the South, we always congregated around churches. Believing in God felt a lot like believing in each other. For many years, I equated the belief in a higher power with the presence of hope.

I lived in a mid-sized city, Rome, Georgia, which prided itself for its distance from the interstate but still had its fair share of rush hour traffic. You couldn’t easily walk from one end of town to the other, but you could navigate downtown on foot. Three rivers met just behind Broad Street, and people were usually standing down by the banks fishing as the clock tower announced each passing hour.

If you get in a car on Broad Street and head south, passing the fairgrounds, which fill up each October, and continuing past an iconic lot filled with stone statues, another filled up each holiday with inflatables, and finally past the expanses of woodlands beset in recent years by controlled burns — you will reach Kingston, Georgia. Growing up in Rome, we told local legends about avoiding Kingston at all costs. We said it was haunted or dangerous, the sort of place you’d get lost in forever.

Always curious, I longed to find out if the stories were true. Then, in my early 20s, I met a man who had recently opened a scenery studio in Kingston. Seeking refuge from the madness of Atlanta, he’d traveled north to a former lumber yard that before that had been a railroad wye – an important transportation hub during the Civil War.

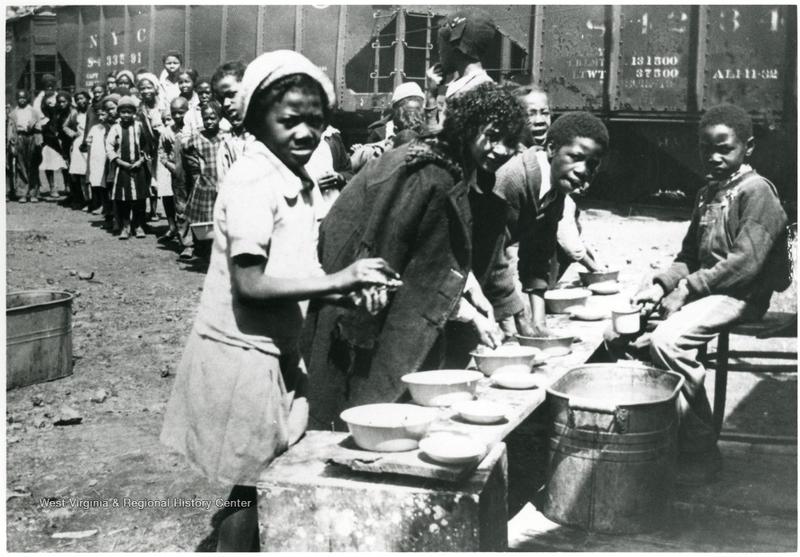

Kingston has felt a lot like a forgotten town. You can walk from one end to the other. There is a park in between. Railroad tracks, on which trains still run, cross through the center of the town. We are known for our high number of Civil War landmarks and not much else. There are churches on many of the corners, and the conflation of religion with hope there feels almost as practical as fanciful. Specifically, churches provide evening childcare for many children of working parents and give food and clothing to a population in need.

When I married in 2007, a pastor from a local church officiated the ceremony. Four years after that, I found myself sitting on the town’s active railroad tracks. Some of me wanted to die. Nonetheless, I chose to live. I also began the long process of quietly losing my religion. This wasn’t because my troubling circumstances caused a lack of faith. Rather it was because, while sitting on those tracks, my inner will inspired me to go back inside, hug my child, seek out treatment for depression and ultimately be brave enough to leave what grew to be an unhealthy marriage. I had called out to God and received the clear message to call upon myself instead and rise beyond the stories of my childhood. I had not so much renounced my faith in God as found my faith in myself.

For many of my neighbors, that still sounds a lot like blasphemy. For others, it sounds like an opportunity for them to put me in their prayers. I greet both attitudes toward my agnosticism with a smile. There is no need for it to stand between us, and it doesn’t most of the time. At 10, my daughter can safely walk to local stores by herself and have picnics in the park with her friends. Mine is the house where local children come to pass hours and eat chicken nuggets and cookies before pulling out flashlights and making their way home at dark. We help each other plan parties when it comes time for them to celebrate birthdays. We share folk remedies and food. Within our community, there is a lot of love. There is also a lot of poverty, addiction and emotional pain. Whether or not our comfort comes from religion or elsewhere, we show each other kindness and respect.

I am writing to share that revelation. During a time when the United States is divided pointedly along party lines, I’ve found security and peace in rural America. In many ways, my small, taboo town has become its own nexus of hope. The simple fact that we keep showing up daily, bearing witness to each other’s lives, is enough.

Kelli Lynn, a native of Northwest Georgia, is an author, activist and entrepreneur. More of her writing is available on Medium.

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.