The words of a fire department chief from the small town of Windsor, North Carolina, come to mind as Corey Davis tries to describe how his state’s weather has changed in recent years.

A climatologist at the State Climate Office of North Carolina, Davis recalls attending a meeting about climate change in early 2017 where scientists were discussing extreme weather events such as Hurricane Matthew, which only months before had caused $4.8 billion in damage, including $400 million in agricultural losses.

The fire chief from the town about 15 miles in from the coast stood up to ask, “How frequent is this sort of event?” Davis says. “One in 500 to 1,000 years,” he was told. “Then we have people in our town who must be 1,000 years old!” he replied.

“The storms we’ve seen in the last 20 years or so,” Davis concludes, “we just don’t have a historical comparison, and they’ve been catching farmers and others completely off guard.”

What’s more, the fire chief’s comment was made before Hurricane Florence, which made landfall in North Carolina on Sept. 14 of last year and “did the work of two or three storms on its own,” Davis says, causing an estimated $1.1 billion in crop damage and livestock losses, according to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety.

Agriculture is vital to the Southeast’s economy; Appalachian states Georgia and North Carolina are among the top 15 states in agricultural production nationwide. And immigrant farmworkers are vital to the industry; they make up more than 90 percent of all farmworkers, according to most estimates. That includes farmworkers with temporary, H-2A visas, and farmworkers who are undocumented.

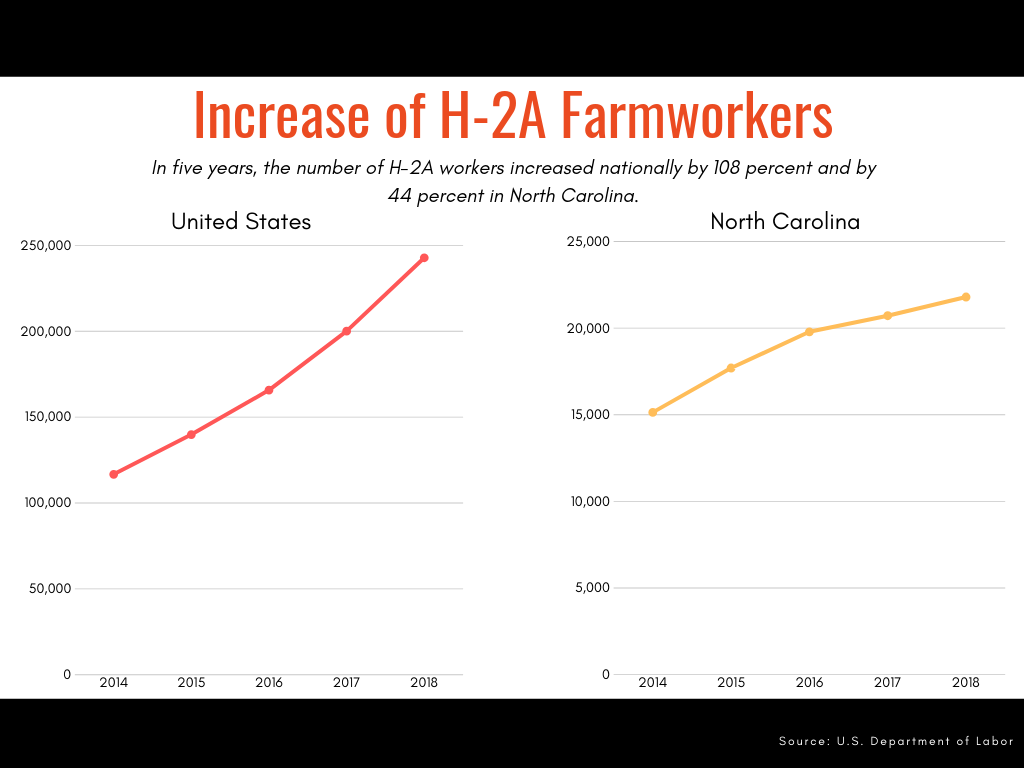

In North Carolina, about 20,000 farmworkers have H-2A visas this year, and an untold tens of thousands more are undocumented. Growers have used an increasing number of H-2A farmworkers in recent years and Georgia and North Carolina are also among the top 10 nationwide in this category.

Scientists are predicting extreme weather events linked to climate change will become more common, but states and the federal government have overlooked immigrant farmworkers not only in planning for severe storms, but also for changes such as rising temperatures. Not including immigrant farmworkers could negatively impact the agricultural economy of these states, while also placing the health and safety of tens of thousands of farmworkers at risk.

When Hurricane Florence landed in North Carolina, the storm didn’t just set records for the amount of rain it dumped, or for being one of the top 10 most economically destructive storms in U.S. history, causing more than $25 billion in damage all told. It was also the first time scientists tried to make a unique kind of forecast, as the storm was in progress.

Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, together with several colleagues at Stony Brook University, published an analysis Sept. 11, 2018, estimating how much more rain Hurricane Florence would dump on the state due to climate change. The storm made landfall on Sept. 14.

The researchers estimated that global warming would increase the storm’s rainfall by about 50 percent.

“A change in precipitation due to global warming has already emerged,” Wehner said. “In storms like Florence and Harvey, the increase is more than you might expect.” One reason, he said, is simple physics: warm air can hold more water.

In fact, the amount of rainfall alone from Florence, reaching nearly three feet in some areas, was “completely unheard of in history,” climatologist Corey Davis says.

Hurricane Florence also ranged further inland than previous storms and was “more wide-sweeping, because previous storms centered on one part of the state,” Davis says. He observed that in the western part of North Carolina on Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak in the Appalachian Mountains, Florence brought 74 mph winds and a record-setting 14 inches of rain in one day.

Although a lot less rain fell in the western, mountainous part of the state than on the coast or eastern lowlands, this much rain “has an impact, and sweeps across the state in rivers, flooding in a second wave” after the storm, Davis says.

Wehner, who contributed to a chapter on “extreme storms” in the National Climate Assessment, a Congressionally-mandated, peer-reviewed report, says in the future, he “wouldn’t be surprised if storms like these would affect all 100 counties” of North Carolina. But storms are not just ranging wider geographically, they’re also becoming more frequent.

Recently-compiled data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that in the last three decades alone, the number of severe storms causing at least $1 billion in damage in North Carolina increased from two during the 1980s to 20 in the last nine years alone. Other Appalachian states are seeing similar changes. In Georgia, those numbers increased from two to 27. In Tennessee, they’ve gone from one to 28, and in South Carolina, from three to 20.

The fourth National Climate Assessment cited economic projections that “southern and midwestern populations are likely to suffer the largest losses from projected climate changes in the United States,” and noted that “[e]xtreme rainfall events have increased in frequency and intensity in the Southeast, and there is high confidence they will continue to increase in the future,” which will likely lead to future crop damage and livestock loss due to severe weather events and, in turn, less work for immigrant farmworkers as growers recover.

The National Climate Assessment points to another change in store for the Southeast: “while some climate change impacts, such as sea level rise and extreme downpours, are being acutely felt now, others, like increasing exposure to dangerously high temperatures—often accompanied by high humidity…are expected to become more significant in the coming decades.”

Indeed, “[s]ixty-one percent of major Southeast cities are exhibiting some aspects of worsening heat waves…a higher percentage than any other region of the country,” the report notes. The most pronounced effect to date has been in night time temperatures above 75 degrees Fahrenheit, with the number of nights this decade more than twice the average from 1901 to 1960. The so-called “freeze-free” season has also been more than one and a half weeks longer than any period in recorded history.

Increased temperatures, along with drier summers and wetter falls, could also decrease productivity for crops like cotton, corn, soybeans and rice, as well as tree crops like peaches. This would mean less work for immigrants: the report includes a projected loss of a half-billion hours of work in agriculture, timber and manufacturing by the end of the century.

But higher temperatures can also lead to injury and death for farmworkers in the meantime — as happened in Georgia last year, when a 24-year-old man who had come from Mexico less than a week earlier died picking tomatoes in temperatures approaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

But neither the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) nor other agencies have created federal heat stress standards, said Virginia Ruíz, director of occupational and environmental health at Farmworker Justice, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization. Currently, Washington and California are the only states that have them, Ruíz said. Her organization and 130 others have petitioned OSHA to create such standards as breaks, shade and water for workers exposed to extreme heat.

“I’m particularly worried about heat waves,” Wehner says. “This is a population that makes its livelihood by being outside … [and] the effect of heat on agricultural workers in this region has not been adequately explored.”

Despite their importance to the economic life of these states, immigrant farmworkers “are seen as replaceable cogs,” said Karen MacClune, executive director of the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International, a Boulder, Colo.-based nonprofit organization that researches climate change and helps communities respond to natural disasters.

In a recently-published report called “Hurricane Florence: Building Resilience for the New Normal,” ISET-International recommends using “economic motivators as levers for action” in planning for natural disasters. Since “[t]his population is vitally important to the economy,” the private and public sector should include it in plans, says Rachel Norton, an author of the report.

Such planning would address the vulnerabilities of H-2A visa-holders and undocumented farmworkers during and after natural disasters, which include: not speaking English; not knowing the lay of the land; not having transportation; not wanting to violate H-2A contracts or act without guidance from growers; and not wanting to expose themselves to immigration authorities, if undocumented. In addition, in the wake of extreme weather, neither population is eligible for most federally-funded, state-administered disaster relief.

“Politicians should have a plan, and dedicated budget, focused on vulnerable populations, including African-Americans and immigrants,” says Juvencio Rocha Peralta, executive director of the Association of Mexicans in North Carolina (AMEXCAN), an organization that has worked since 2001 with Hispanics in a 29-county area in the eastern part of the state. “But they never have.”

The combined impact of being uniquely vulnerable and largely excluded from disaster planning is that survival often depends on the kindness of strangers and the efforts of nonprofit or community organizations, most of which are under-funded. After storms recede, an untold number of undocumented farmworkers leave states where they’ve been working, upon discovering that there is little to no way of recovering housing and other material possessions lost to storms.

“Disaster response is all about systems,” says Scott Marlow, senior policy specialist at the Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI), a North Carolina-based nonprofit organization. Marlow has worked on 18 natural disasters. “The problem is the systems are not well-equipped on the front end to respond to the needs of H-2A or undocumented farmworkers.”

In the end, this may wind up jeopardizing the broader economy, says MacClune, of ISET. “At what point do we think about our food supply?” she asks. “If a key element is immigrant labor…how do we think about them?”

This is the second story in Unseen, a series exploring how climate change related severe storms are impacting immigrant workers in southern Appalachia. Read more from the series here.