This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.

The Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge’s namesake is apparent upon stepping outside its visitors center in Williamstown, West Virginia. Gazing past bird feeders and the forested bank of the Ohio River, a skinny island looms large.

“So Buckley Island is right across the water from us,” says Michael Schramm, visitor services manager at the refuge.

Buckley Island is one of about 40 river islands spanning hundreds of miles of the Ohio River. The islands were formed by rock and gravel deposited during the Ice Age, and they serve as important habitat for wildlife on the Ohio River, including migrating birds. Over the years, as the river channel has deepened, some of the islands have eroded away. Today, the refuge manages 22.

“Part of the concept of the refuge and why it’s so widely scattered along the Ohio River is that it’s sort of like a little Noah’s Ark that the wildlife can use as they migrate,” Schramm says.

The islands have a unique history. Some were used for farming, oil was drilled on others. Schramm spots a rafter of wild turkeys near an abandoned barn on Buckley Island, about a quarter mile from the visitors center. A century ago, it was home to an amusement park.

Since the refuge’s founding almost three decades ago, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has acquired these river islands, the bulk of which are in West Virginia. A handful fall in Kentucky and Pennsylvania. Largely, the agency has used millions of dollars from the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

The LWCF, as it’s often called, was created by Congress more than 50 years ago as a way to protect the country’s natural areas and ensure Americans have access to them. It’s funded with revenues from royalties on offshore oil and gas drilling.

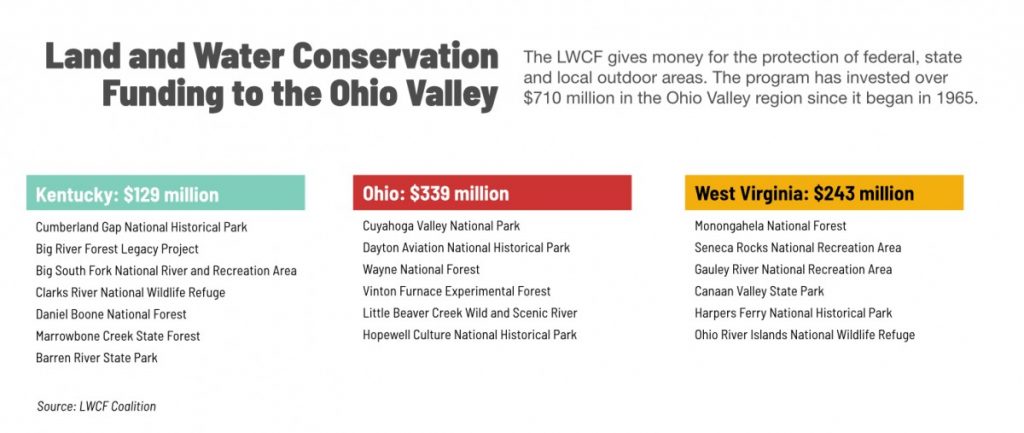

Across the Ohio Valley, more than $700 million from the LWCF has been invested at federal, state, and local parks, forests and wilderness areas and to increase recreation access.

“We like to say the Land and Water Conservation Fund is the most important conservation program that nobody knows about,” said Matt Keller, senior director at the conservation group, The Wilderness Society. “It’s a program that had pretty positive and dramatic impacts all over the country, including West Virginia, and Ohio and Kentucky.”

Despite its popularity, the program hasn’t always been functional. Congress must both authorize the program and fund it, and previous authorization for the LWCF expired on September 30, 2018.

Keller said in today’s divided political atmosphere, passing bills in Congress even with broad bipartisan support can be a challenge, but in February both the House and Senate resoundingly passed S. 47, the Natural Resources Management Act.

In March, President Donald Trump signed it into law.

“It’s a remarkable moment for conservation of public lands,” Keller said. “There haven’t been a whole lot of victories and positive things moving forward in the past couple years, but this is a notable exception.”

Congress, he noted, still needs to provide funding for the program.

The public lands package has a wide reach. Not only did it reauthorize the LWCF, the bill folded in measures that increase access to public lands for hunters and anglers, and designate more than 1 million new acres of wilderness. The legislation also renews for seven years the Every Kid Outdoors program, which gives all fourth graders and their families free access to U.S. National Parks.

More than 100 smaller bills were also added into the final version. Most authorize regionally-specific projects, including in the Ohio Valley.

Battlefield Victory

For years, Mill Springs Battlefield, located near Nancy, Kentucky, was ranked one of the most endangered battlefields in the country. Under the new bill, it’s now a national monument. It will receive funding and support from the National Park Service.

“It’s a big deal for us, something we’ve been working on for about 15 years,” said Bruce Burkett, president of the Mill Springs Battlefield Association.

The non-profit has since 1992 purchased and preserved more than 400 acres of land associated with the 1892 Battle of Mill Springs, the first major Union victory in the Civil War’s western theater.

Burkett said the national monument designation will raise the profile of the battlefield and draw more visitors in to learn about the role Kentucky played in the Civil War.

“Kentucky, for the most part, you know, is truly the brother against brother in this county,” he said, adding that the inclusion of Mill Springs Battlefield as a national monument is an important step. “I think it does help further the understanding the American Civil War.”

A second Kentucky Civil War battle site, Camp Nelson, which was one of the largest training depots for African-American soldiers, was also designated in the bill.

Forest Heritage

A few hundred miles away, the Appalachian Forest Heritage Area is also getting a new name, adding “national” to its title after years of being stalled by Congress.

“We’re just incredibly excited about this. We’ve been working on this for so long,” said Phyllis Baxter, executive director of the nonprofit that manages the diverse, 18-county swath of forest highlands in West Virginia and western Maryland.

She said the official National Heritage Area designation increases the resources available to promote the area.

“This will get us branding on the National Park Service website,” Baxter said. “We can do a Passport program. There’s a lot of things that we could do, that will have access to now that we didn’t have access to before.”

Baxter said one hope is that national visibility boosts tourism in some of the rural communities in the heritage area, providing a sustainable source of economic diversification.

“Whatever we can do to help those small towns find ways to diversify their economy and whether that’s, you know, tourism or other small business or whatever works in each place we want to support that,” she said. “And we hope that this will help.”

Economic Boost

The Natural Resources Management Act also includes language that increases funding for all National Heritage Areas, and specifically expands the funding cap for the Wheeling National Heritage Area, from $13 million to $15 million. WNHA was established in 2000 and encompasses a 12-square-mile region throughout Wheeling, located in West Virginia’s northern panhandle.

A 2017 economic impact analysis found from 2014-2016, WHNA generated $86.6 million in economic impact largely from tourism. The heritage area also supported 1,109 jobs and generated $6.4 million in tax revenue.

Supporters of the LWCF also point to billions of dollars in economic benefits associated with outdoor recreation.

Angie Rosser, executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Coalition, said the program benefits communities at all levels and has played an important role in expanding the state’s whitewater rafting industry.

“When we think of river access, I mean LWCF immediately comes to mind in the ways that it’s benefited rivers like the Gauley, which of course attract tens of thousands of people from all over the world to experience our world-class, whitewater rapids,” Rosser said.

Every public access site on the Gauley River was made possible using funds from the LWCF.

“Whether it be a town swimming pool, or state park or national forest or driving by Seneca Rocks, almost everyone has been touched in some way by the support of the Land and Water Conservation Fund,” she said. “It’s made those places what they are today and accessible for us all to enjoy.”

This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.