Robert Bailey was a coal miner for 36 years. He began working in McDowell County, and after it became too hard to breathe, he retired from a mine owned by Patriot Coal in Boone County. Bailey first told his story with WVPB in June 2014. He shared his final story with Inside Appalachia host, Jessica Lilly, on February 15, 2019.

“It’s a struggle just to receive the help that you still need,” Bailey said back in 2014. He was still in the process of a lung transplant. At this time, Bailey was waiting to hear if Patriot Coal’s insurance company, Underwriters Safety and Claims, would approve his appointment for a medical evaluation. He’d already had to cancel one appointment.

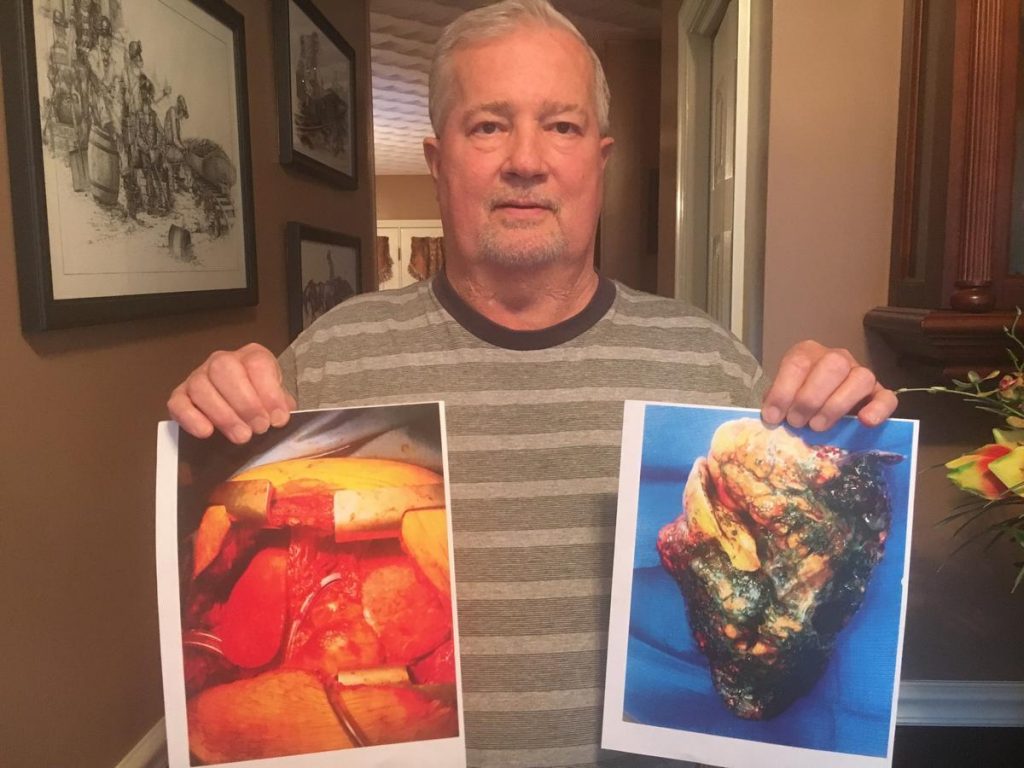

Bailey had already been approved for federal black lung benefits by the U.S. Department of Labor and his doctor told him he needed a double lung transplant.

Black lung disease made it difficult for Bailey to breathe. “It’s almost like drowning,” he said.

As Bailey waded through another bureaucratic process, the clock was ticking, and he was running out of time.

“They told me that as soon as my testing was done that they’d put me on a list,” Bailey explained. “So that tells me that they don’t think that my lungs have very much life left in them.”

Transplant Grants Bailey 3+ More Years

Four months later, Robert Bailey’s lung transplant was approved by Patriot Coal’s insurance company. But when the bankruptcy was finalized, the company had shed these responsibilities. So, Bailey said the money came from the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, which covers black lung medical benefits for bankrupt coal companies.

A double lung transplant comes with its own set of health challenges. About half of all adults who receive a double lung transplant live just five years after the surgery.

Robert became an advocate for miners with black lung and spoke twice to Congress during Senate hearings, urging lawmakers to act quickly in order to reduce the backlog of black lung cases still needed to be evaluated.

“I’m hoping that through my experience other people could maybe have better results,” he said.

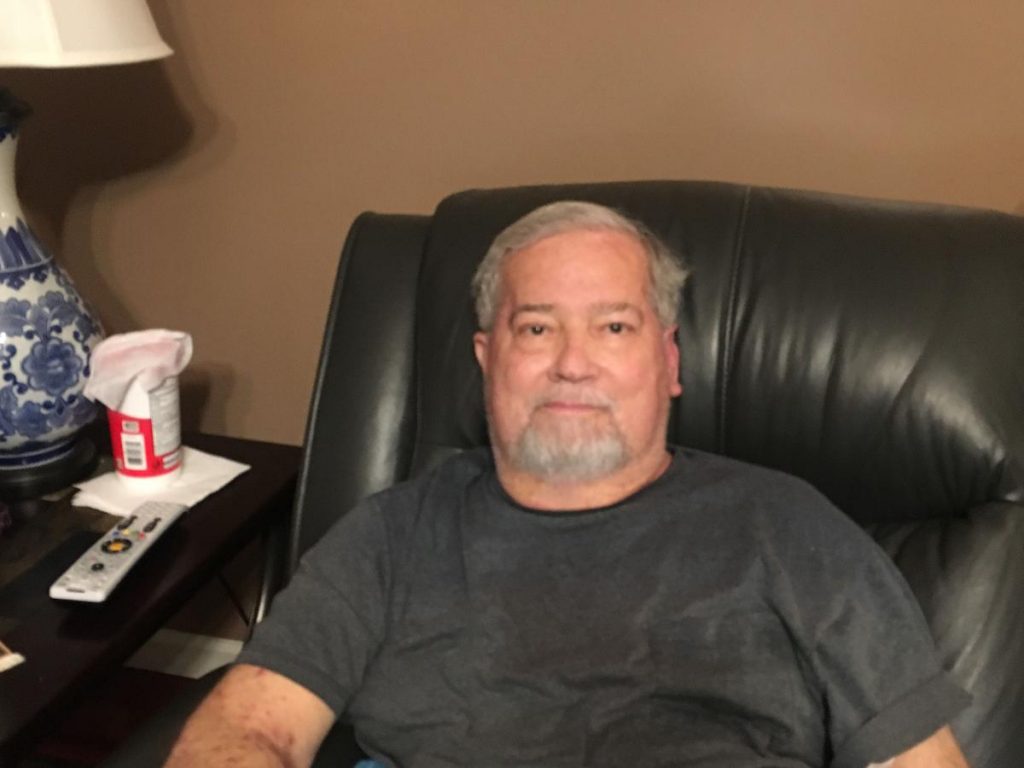

Final Days

About two months ago, Robert learned he had an aggressive form of liver cancer. Doctors gave him weeks to live, and he was put on hospice care when he got home. He wanted to share more of his story.

“I wasn’t really shocked about it really,” Bailey said. “It wasn’t really news that I was looking forward to hearing, but I know it was news that we would have to deal with. But God gave me first breath. He’ll take my last one.”

Robert reflected on his struggle with black lung. He said that doctors told him his liver cancer was probably linked to medications he took as part of his treatment after his lung transplant. Still, he said, these side effects of his transplant wouldn’t have even been an issue if he hadn’t contracted black lung to begin with.

Mr. Bailey was a humble man, but he still wanted to share his story. He said he hoped that his suffering, and his death, wouldn’t be in vain.

“Even though I have been blessed with this extra time that I wouldn’t have had, it would be so much better in the long run if the disease itself would be conquered,” he said.

Robert said he hoped his story might help inspire lawmakers to take more steps to improve health conditions for other miners, and perhaps even prevent other coal miners from the same suffering. He pointed out that laws to protect coal miners typically don’t change until miners die, and sometimes not even then.

“Most laws across the nation, most laws [have] been written with blood. I don’t want the things I went through just to drop and no knowledge to be gained.”

As for advice for any young miners today, he said it’s important to do a good job during the day but it’s also important to be able to come back.

“I know a lot of them does a lot of things for the money, and they’re offered a lot of money to meet certain goals. But you can meet a goal today that will take you out of this world tomorrow,” Bailey warned.

Robert Bailey passed away 28 days after this conversation.

This story is part of an episode of Inside Appalachia about black lung disease. It was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.