This article was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.

Toni Wilkinson has seven children, three of them under six, and all of them home-schooled. So her house on a Lexington, Kentucky, cul-de-sac is rarely quiet.

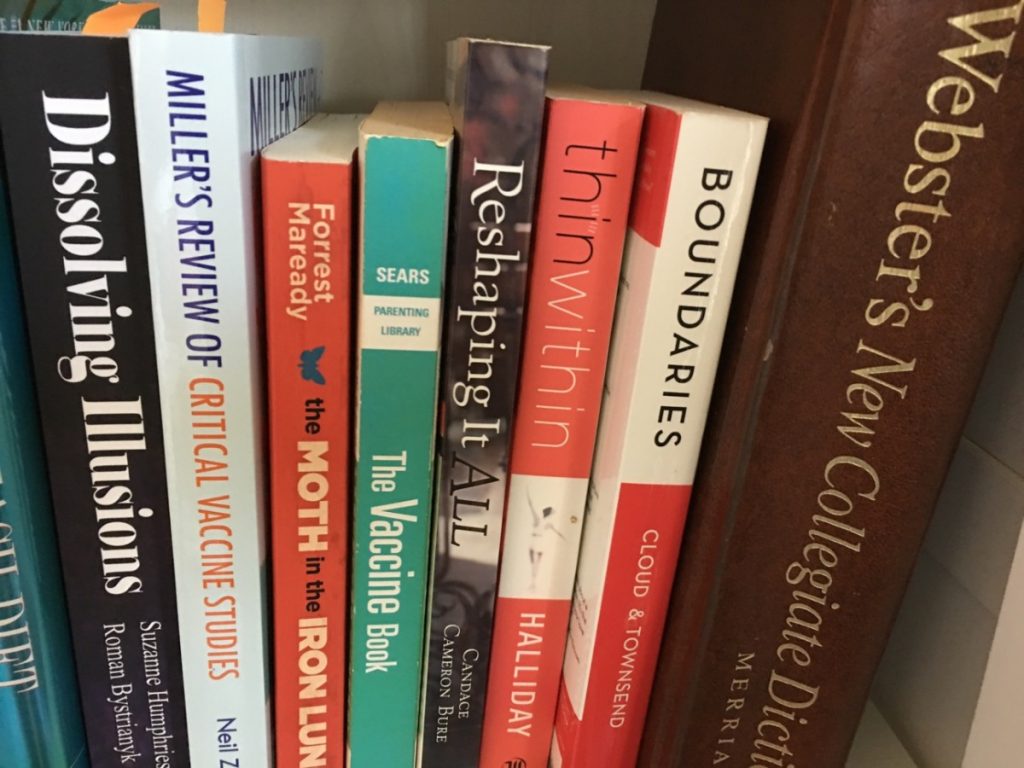

Just inside the front door are bins filled with shoes, piles of jackets on a long bench. Across the room is the family library, crammed with school books. Crowded among them are controversial titles critical of vaccinations, the books Wilkinson used in her own homework researching vaccines.

“I just started to have questions, it was just this lingering doubt that I can’t really explain,” she said.

As those doubts grew over the years, vaccinations for her children decreased. Her two oldest children are fully vaccinated. The next two received the required shots only until middle school. Her three youngest are not vaccinated at all.

Wilkinson said her faith ultimately informed her choice. She learned that stem cell tissue from abortions had been used to produce some vaccines.

“And so that became a big issue for me because we’re very pro-life,” she said.

Kentucky is among 47 states that allow some form of religious exemption from vaccination requirements for children to attend public schools. Kentucky is also among 22 states that have reported cases of measles this year.

Two decades after the U.S. had essentially eliminated measles, the viral disease is roaring back. Health officials recently reported nearly 700 cases of measles in the U.S., the most in 20 years, and they point to a growing trend against childhood vaccination as a cause. Some measles outbreaks in New York and Ohio have been associated with religious communities opposed to vaccination, and that has intensified the debate about religious exemptions.

Kentucky and neighboring states in the Ohio Valley provide a case study and the potential for some timely lessons on the public health implications of vaccination exemptions. While Kentucky and Ohio allow the exemptions, West Virginia does not.

Vaccine History

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a few vaccines were developed using human cell cultures derived from two legal abortions in the 1960s. Researchers maintain those cell lines in laboratories and no additional fetal tissue has been added since they were originally created.

But Wilkinson’s concerns resonate with others who staunchly oppose abortion.

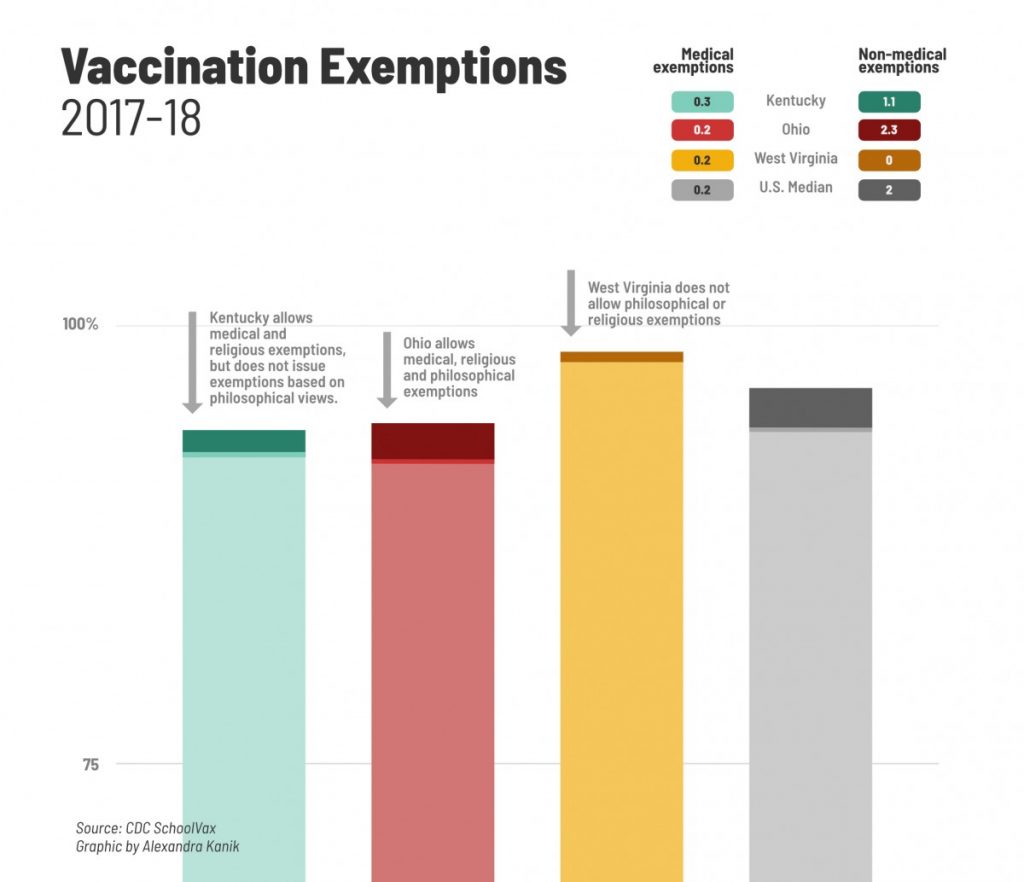

Kentucky and Ohio allow parents with religious objections such as these to enroll a child in school without proof vaccination. West Virginia does not.

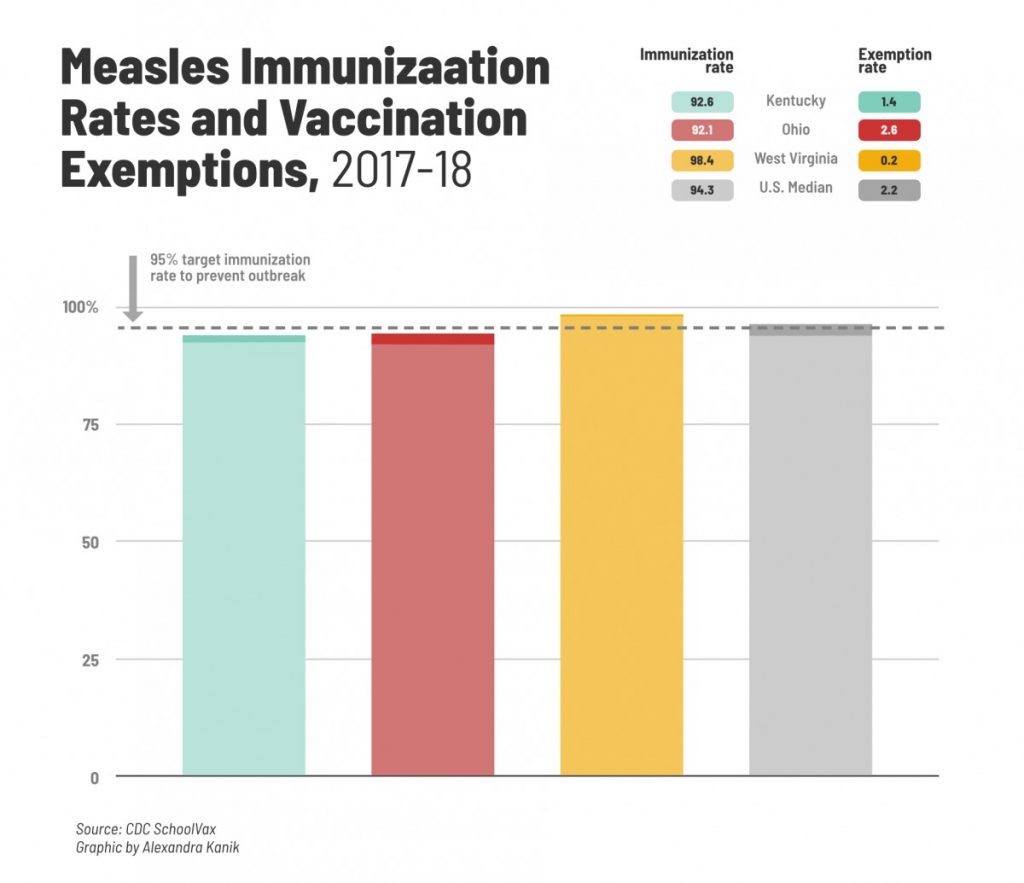

“West Virginia started having state laws about vaccines in the late eighteen hundreds and there’s never been any type of religious or personal belief exemption in our laws,” said Jamie Lynn Crofts, a civil rights attorney in Charleston, West Virginia. She said with its 98 percent vaccination rate, well above the national average, West Virginia could be a model for other states.

“Looking at our scheme and how effective it’s been could be a great guide to states who are looking to reform their laws to stop outbreaks in the future,” she said.

Vaccination rates in Kentucky and Ohio are 92.6 percent and 92.1 percent, respectively, both below the national median rate of 94.3 percent.

Crofts said how you feel about vaccination can depend on when you were born. Most Millennials, for example, have no personal experience with measles and may not see it as a threat.

The CDC reports that before the measles vaccination program started in 1963, an estimated 3 to 4 million Americans got measles each year. Only about 500,000 cases were reported each year to the CDC. Of these, 400 to 500 died, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 1,000 developed encephalitis (brain swelling) from measles.

While the current outbreak seems insignificant against those historic numbers, health officials are concerned. The public health benefit of a vaccination depends in part on what’s called “herd immunity,” achieved only when a high percentage of vaccination keeps the disease at bay. A study from Oxford University found that 19 out of 20 people need to be vaccinated to maintain herd immunity against measles.

Religious Reservations

No major American religion explicitly seeks to forbid vaccines. Some within the Catholic church encourage vaccination. But a subset of church members like Wilkinson reject vaccines on moral grounds because of the past use of fetal cells in some vaccine development.

That religious belief is a key part of a lawsuit brought by the parents of a student at Assumption Academy, a private school in northern Kentucky. Most of the students were not vaccinated, resulting in a recent outbreak of 32 cases of chickenpox. When the Northern Kentucky Health Department curtailed school activities to curb the spread of disease, some students and parents sued, arguing that it violated their rights. The school posted a press statement on the outbreak on its website explaining its beliefs about the vaccine.

“While the Catholic Church does not oppose vaccinations in principle, it does consider as morally illicit the development of vaccines from aborted fetal tissues,” the statement read.

It’s not the first time outbreaks have been linked with a specific religious community.

The CDC connected unvaccinated members of the Amish communities in Ohio to the last record-breaking outbreak in 2014. Researchers found that people in those communities made up nearly half of the cases in the national outbreak.

Dr. James Gaskell is commissioner of the Athens City-County Health Department in Ohio. He remembers that the 2014 outbreak had a lingering impact on the Amish community.

The Amish were resistant to vaccination at first. But, he said, after a few cases of measles, when they recognized the severity of the disease, some changed their minds and began to immunize their children.

Gaskell said that outbreak began after Amish men traveled to the Philippines, which still has a high number of measles cases.

A current measles outbreak in New York has similar origins, Gaskell said. Orthodox Jewish men traveled to Israel and some returned infected with measles, which spread into their community where many others are not vaccinated. The New York outbreak has sparked debate over limiting or eliminating religious exemptions there.

Law Changes

In Kentucky and Ohio, lawmakers are moving in the other direction even though both states have vaccination rates below the national average.

“There has not been any talk about eliminating exemptions to vaccines in Kentucky that I’m aware of at this point,” Kentucky’s Public Health Commissioner Dr. Jeffrey Howard said.

Howard said he supports vaccines and that there are a lot of misunderstandings and myths surrounding them. But, he says, Kentucky is a place where people want to protect personal liberties such as whether or not to vaccinate a child.

He said requests for exemptions are rising and lawmakers are making access to exemptions easier.

In 2017 Kentucky legislators removed the requirement that a physician must sign a request for a religious exemption. Now parents simply sign and submit a notarized form. A bill pending in Ohio would make similar changes to increase access to exemptions.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb was commissioner of the federal Food and Drug Administration from 2017 until earlier this month. He is now a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Gottlieb said religious exemptions are on the rise along with the number of cases of measles.

“I think it would be highly unfortunate if we started to see governments take a more activist role, particularly the federal government, in terms of mandating vaccines, because I think these are issues that have long been held left to state supervision for a lot of good reasons,” he said.

Gottlieb said the surge in the number of infections reflects “a tragic reluctance to embrace what is one of our most effective and safest vaccines.” And that will soon force health officials to make tough policy decisions.

“We’re at the point right now where we’re starting to see outbreaks of such a scope that we are going to reach a tipping point and perhaps some point soon.”

Belief and Backlash

Toni Wilkinson is aware of the controversy around vaccination decisions such as hers.

Wilkinson said her decision has come with backlash, including conflicts within her family and, scathing comments on social media. She and her friends who have made similar choices have become wary of even discussing vaccines with people.

“You read some of the stuff that people say and it can get really nasty. Like, you know, ‘These people shouldn’t be able to have children if they’re not going to vaccinate them.’ It can get very ugly.”

She said she feels certain in her decision. “God places children in families for a reason,” she said. But she adds that she still has brief moments of doubt.

“I think there was still a little fear of like, what if my child got what is considered a vaccine-preventable disease, what am I going to feel?”

“I think there was still a little fear of like, what if my child got what is considered a vaccine-preventable disease, what am I going to feel?”