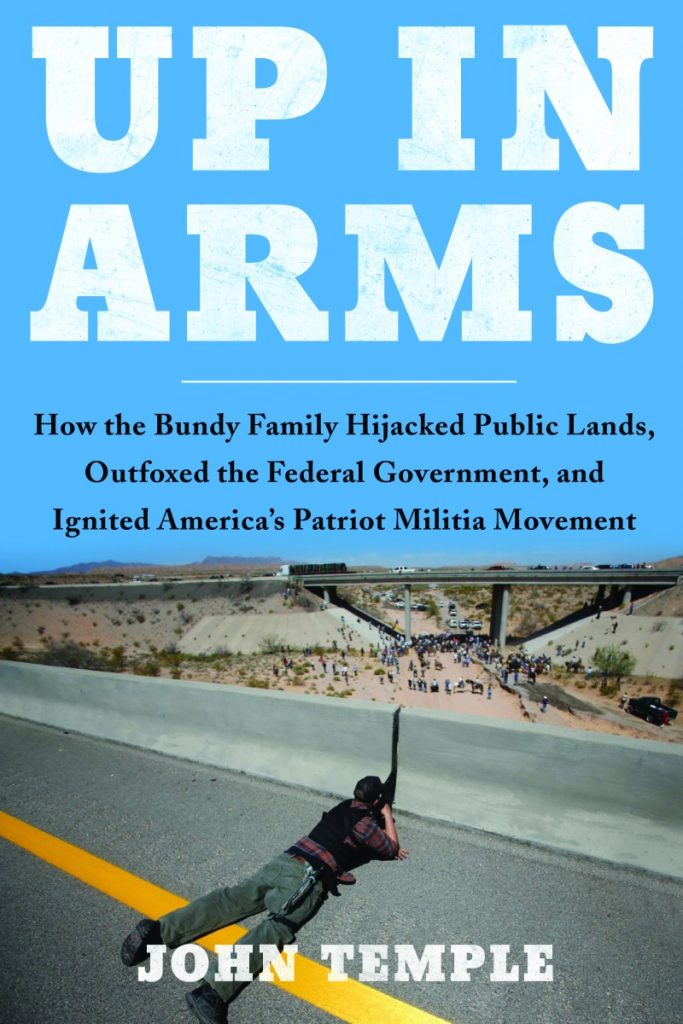

The “Bundy Sniper” photos were stark and disorienting, like wartime images from a Third World hot zone, not a blocked-off interstate highway one hour from Las Vegas.

In one of the photos, a lariat-thin white man in a heavy beard and tactical jacket lies belly flat on the concrete, his semiautomatic rifle wedged in the narrow gap between two concrete jersey barriers. Eyes concealed by dark sunglasses, the rifleman sights down on a group of federal agents who were overseeing a roundup of cattle belonging to Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy.

Five years ago today, as high noon approached, a Reuters photographer snapped the rifleman’s image and it spread around the world. For many Americans, the photo upended the way they understood their country, and widespread disbelief reigned. The Bundy Sniper pointed a deadly weapon at federal agents and got to go home? The Bundys themselves incited an armed mob but got their cattle back? To many, the bulwarks of peaceful society felt a little less substantial. This didn’t happen in the United States.

Not everyone felt that way. As I crisscrossed the West reporting my forthcoming book on the Bundy saga, I realized that the vast numbers of Americans who consider themselves part of the so-called “patriot movement” rely largely upon each other for news. And to them, the Bundy Sniper photos were the opposite of frightening. They were inspiring.

Those on the far right have always created their own information channels, going back to the days when John Birchers and Posse Comitatus traded self-published pamphlets. But when thousands of like-minded people met each other at the Bundy Ranch standoff, the patriot movement’s information network swelled, mostly on YouTube and Facebook. The Bundy Ranch Facebook page, for example, has nearly 200,000 followers.

Another patriot media star – largely unknown to the rest of America – was Pete Santilli, one of the earliest Bundy supporters. Santilli ran a right-wing podcast out of his home in Hesperia, California, and was best known for an episode in which he said he wanted to shoot then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton “in the vagina.” He was accustomed to getting a few hundred views per YouTube episode. But when he traveled to Bundy Ranch and captured video of federal officers tasing Ammon Bundy, Santilli’s stature in the patriot media-sphere skyrocketed.

That video was watched millions of times over the next few days, triggering the flood of patriot militia groups and other sympathizers, including the Bundy Sniper himself, a 30-year-old electrician from Idaho named Eric Parker. Like thousands of patriots, he’d discovered the Bundy story by reading Facebook posts about the government roundup of the rancher’s cattle.

So Parker grabbed his Saiga .223 semiautomatic rifle because it was good for desert shooting, told his wife and two children goodbye, and drove the twelve hours to Bundy Ranch. He wanted people to know about his crusade, so as he often did, he wrote about it on Facebook.

“The citizens of the United States fought the toughest, biggest Army in the world in 1776,” he posted. “Do not think we can’t do it again.”

He arrived to a fantastical sight. A massive camp of patriots, including many militia members, had sprung up in a stretch of remote desert. They were prepared to face off against federal officers who were holding Bundy cattle at a military-style temporary command post a few miles away. Tracking the situation through social media and undercover agents, the feds were alarmed; the FBI had never witnessed a patriot uprising of this size.

After the standoff, the Bundy Sniper photos took on a life of their own. They flew back and forth on the Internet. People added words to the images, creating memes. The photos made their way onto T-shirts, some with the word “Resist” baked into Parker’s prone silhouette. Almost two years after the standoff, patriots were outraged when an FBI team arrested Parker and eighteen other people in the case. Later, they celebrated when a federal judge threw out almost all charges against the defendants due to prosecutorial missteps. Patriots eschewed traditional media coverage of the case but dissected every step of Parker’s legal journey via daily streaming commentary on Facebook.

I want people who read my book to understand what it was like to live within that information silo. The Bundy Sniper photos may have appeared outlandish and jarring to the rest of us, but for the denizens of the patriot media universe, Parker’s prone silhouette was no more than a physical extension of what they were saying on Facebook.

Even I wasn’t immune. After I spent more than a year interviewing scores of patriots and watching hundreds of their videos, the Bundy Sniper photos no longer appeared shocking. You can only live so long in that hermetic media universe before taking up arms against the feds begins to look like a reasonable response.

John Temple is a professor of journalism at West Virginia University and the author of the forthcoming “Up In Arms: How the Bundy Family Hijacked Federal Lands, Outfoxed the Federal Government, and Ignited America’s Patriot Militia Movement.”