An active HIV cluster of 28 known cases has been confirmed in Cabell County, West Virginia, primarily among the area’s population of intravenous drug users, according to the state’s Bureau for Public Health.

The cluster, tracked from January 2018 to the present, represents a sharp uptick from the baseline average of eight cases annually over the past five years. This is the first notable HIV cluster in West Virginia where intravenous drug use is identified as the main risk factor, said Dr. Michael Kilkenny, physician director of the Cabell-Huntington Health Department.

In Appalachia, HIV is typically a rare diagnosis compared with coastal cities. This latest cluster represents a continuing shift in how HIV is most often spread, from men having risky sexual contact with other men to intravenous drug users, Kilkenny said.

Other areas in the region are likewise experiencing HIV clusters, including the Cincinnati metro area and smaller pockets scattered around West Virginia.

More than 20 of the 28 known HIV cases are Cabell County residents, Kilkenny said, while the remainder live elsewhere but may have been diagnosed at one of the county’s medical facilities.

The West Virginia Bureau for Public Health characterizes a cluster as being confined to a certain population – in this case, IV drug users – where it may be able to be controlled with minimal risk to the general public. An outbreak would indicate the disease is spreading beyond that initial group.

Kilkenny said there is no model to predict how much Cabell County’s cluster could grow, and declined to speculate.

A true-life worst case scenario was lived out around 250 miles down the Ohio River in 2015, when rural Scott County, Indiana, suffered an HIV outbreak infecting 181 people among a close network of residents sharing needles to inject opioids.

Cabell County is estimated to have more than 1,800 active IV drug users, so introducing HIV into that population is a point of major concern, Kilkenny said.

However, he continued, Huntington is well-equipped with the systems already in place to treat substance use disorder and that at-risk population, meaning it’s better prepared to face the spread of HIV than a community starting from scratch.

“We know how many people we have and we have outreach already into that population,” Kilkenny said.

“So while on the one hand that sounds like a scary number, on the other hand I don’t think that another community, that I could name, has that information going into the intervention.

“So I think we’ll be able to intervene quicker and more effectively than a community who doesn’t know what their population is or doesn’t have programs in place that touch those people.”

The main push of the plan to treat HIV in Cabell County – which has been in the works for about six weeks between the county and state – is to identify every case and refer individuals to treatment, Kilkenny explained.

Even though HIV isn’t curable, medication can now drive down the viral load in a person’s blood to the point where it can no longer be spread.

The plan also includes an ongoing public awareness campaign to encourage those at risk to get tested, and to reduce stigma surrounding the disease in the general public.

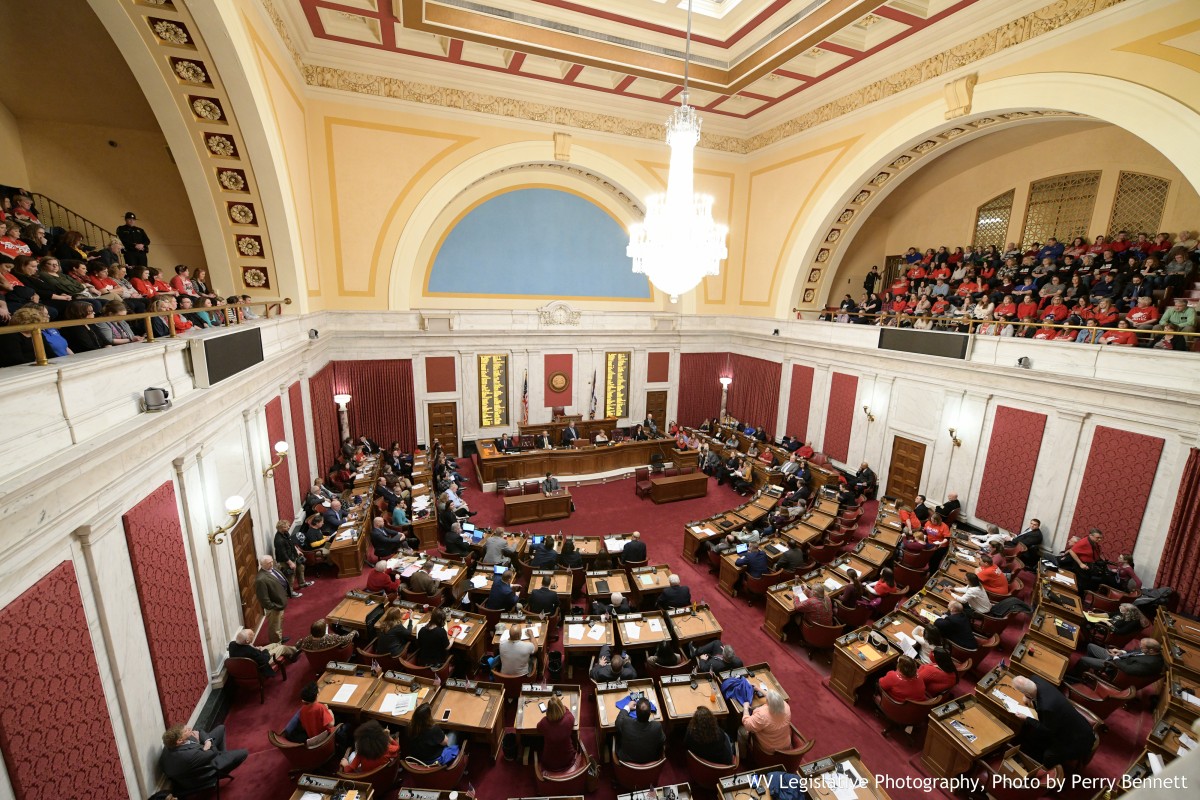

The health department hosted a public forum on HIV on Feb. 19 to offer information on the disease. It featured state and local experts.

“It’s important for people to know that HIV is not the death sentence it was 30 years ago, and that it’s not spread by social contact like hugging or shaking hands,” Kilkenny said.

“Those people should have no concerns at all about HIV,” referencing those who don’t engage in known risky behaviors.

This article was originally published by the Herald-Dispatch.