This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.

West Kentucky Farmer Barry Alexander doesn’t have an answer on when the Trump administration will reach a trade deal with China, now a year into tariffs that have hamstrung some Ohio Valley industries.

Alexander is optimistic these continued negotiations will be worth it, but his plan in the meantime lies in massive, silver storage bins on Cundiff Farms, the 13,000-acre operation he manages.

He pulls a lever, and out tumbles a downpour of pale yellow soybeans.

“These beans have been in here since Halloween day,” Alexander said. “The large bin on the right, that’s 350,000 bushels. The next-size bins down, that’s 180,000 bushels. To give reference, a thousand bushels is one semi-truck load.”

He’s been trying to hold onto about half of his soybean and corn bushels, waiting to see if he can sell for a better price before he’s forced to start planting again in early April.

Crop prices have crashed partly because of Chinese tariffs, and the losses have put a strain on some farmers he knows.

“There are farmers that have decided to retire because they didn’t want to work through these things now. We’re to that point,” Alexander said.

Alexander said he’s survived in part because his sprawling farm has resources to work with: eight full-time employees, two new $550,000 combines he traded up for, and the storage bins to help ride out bad crop prices.

“Our large structures are not cheap, but financially for our farming operation, they’re a necessity for us to do what we do,” Alexander said.

Farmers like Alexander are coping with losses from tariffs and a continuing trade war, and it’s not clear when it will end. A March 1 deadline for negotiations with China was delayed indefinitely by President Trump, and an agreement with Mexico and Canada that Trump signed in November has yet to be ratified by Congress. The retaliatory tariffs on U.S. crops and dairy remain, compounding problems caused by overproduction and low crop prices, and small farmers are suffering the most.

Size Matters

“If you look at all the large farmers, these guys have the storage facilities to wait out bad prices,” Kent State University-Tuscarawas Agribusiness Professor Sankalp Sharma said. “For a lot of these small guys…they couldn’t actually store their commodity, they still had to deal with those lower prices.”

Sharma and others argue grain prices have been low for five years because farmers are overproducing, and tariffs are only making the situation worse.

“The United States soybean harvest this year in general was just crazy. There was a bumper crop, and prices were down because of that,” Sharma said. “This was just your classic demand and supply situation.”

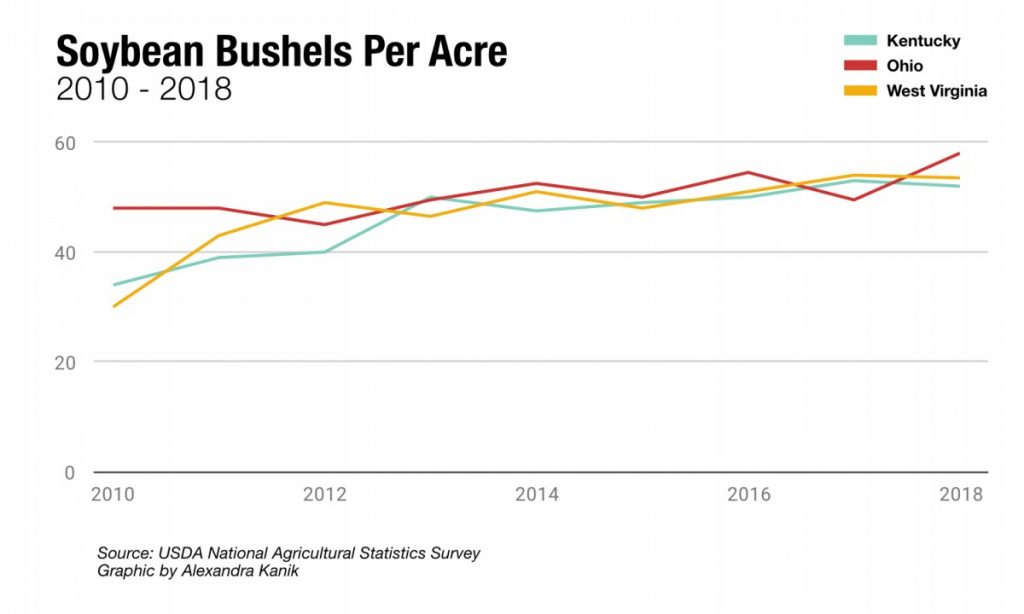

Both Ohio and Kentucky set records for soybean harvests in 2018: 289 million bushels and 103 million bushels, respectively. This is up significantly compared to two decades ago, when Ohio harvested 162 million bushels and Kentucky harvested a little over 24 million bushels in 1999.

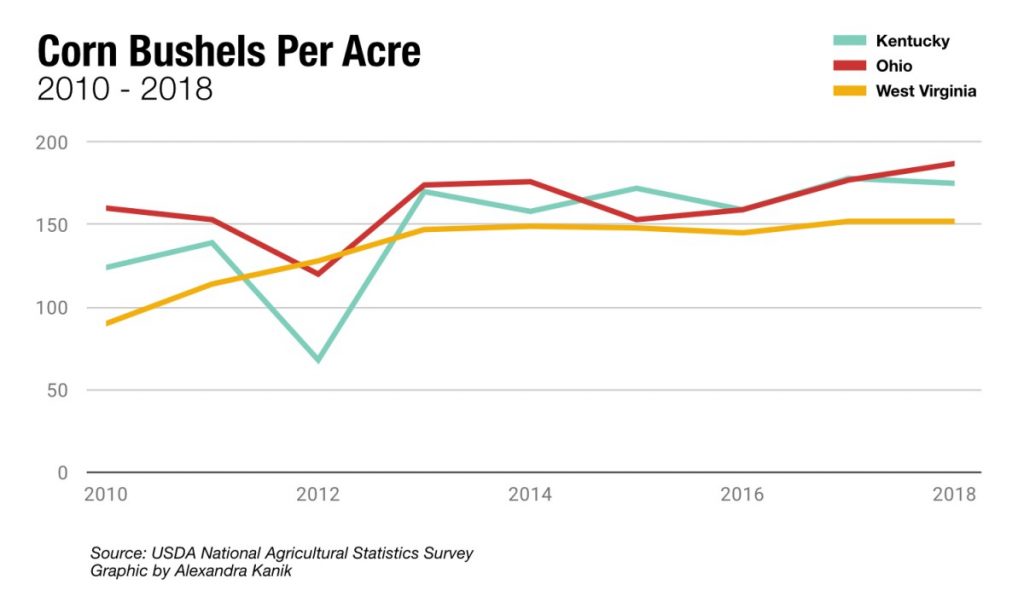

Farmers are also becoming more efficient than ever before — Ohio set records in 2018 for most corn and soybean bushels produced per acre.

Oversupply problems haven’t been limited to grains, though. Small dairy farmers are also dealing with excess supply and tariffs, with hundreds of cases of extra milk being dumped at Ohio Valley food banks.

Farms At Risk

Greg Gibson’s operation is small, but his family has made it work for decades. He milks 80 cows at his dairy farm in Bruceton Mills, West Virginia, and he took over the operation in 2002. The past year of tariffs hasn’t been easy.

“Everything’s down. Historically, if milk price is down you can sell some corn or you could sell some replacement animals are something,” Gibson said. “But nothing has a lot of value to sell right now, so it’s really hard to generate any additional revenue. And a lot of that is because of the trade problems we’re having.”

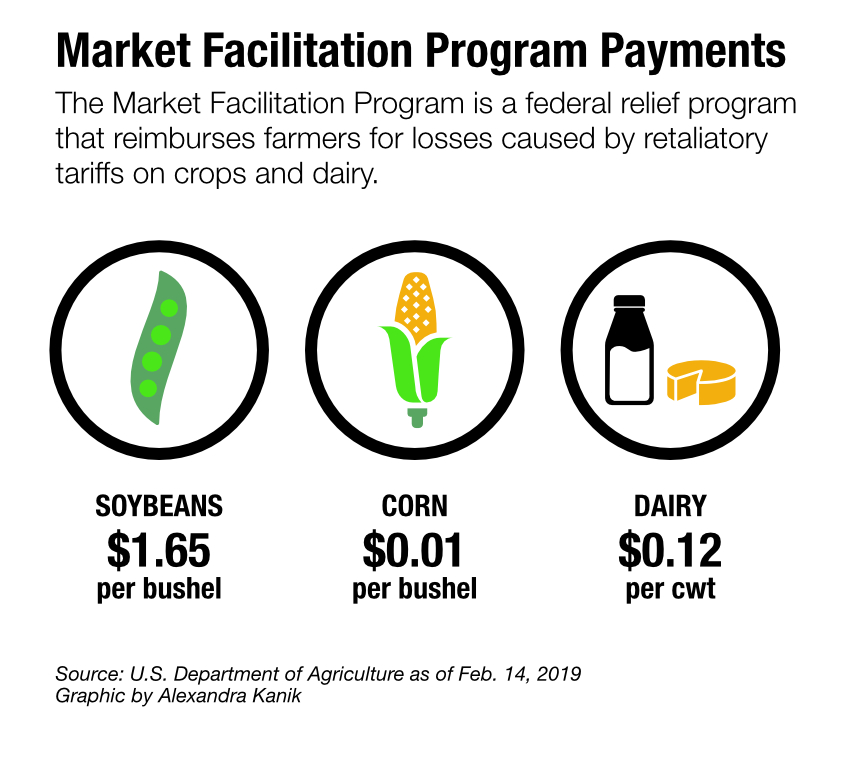

Like many Ohio Valley farmers, Gibson is receiving payments from the $12 billion in federal relief from the Market Facilitation Program intended to to help those who suffer losses from tariffs.

Gibson appreciates Trump’s efforts to renegotiate trade deals, and like Alexander, is cautiously hopeful about the prospects of new trade deals.

But he said he’s also disappointed in Trump because the payments are not nearly enough to recoup his losses. He says milk’s price has plummeted nearly a dollar per hundred pounds of milk sold and the payments only reimburse 12 cents of that.

“I would have rather him said ‘I got to do this. You’re going to take the hit. Sorry.’ Don’t promise me you’re going to take care of me and then don’t,” Gibson said.

Some commodity associations including the National Corn Growers Association and the National Milk Producers Federation have called on the Trump administration in past months to bolster what they call lackluster relief payments.

Gibson’s squeezed budget has had him extend paying off his farm loans and put off paying several repair bills. He’s also had to put up his 150-year-old family farm as collateral for his loans.

Farm lenders say Gibson’s situation isn’t unique right now. Senior Vice President of Agricultural Lending Mark Barker helps oversee lending for Farm Credit Mid-America, which serves most of Ohio and Kentucky.

“Are we doing things differently? Well, sure,” Barker said. “Because we have customers coming in now and telling us ‘I’m struggling at this point. I’m challenged.’”

Barker said while most people are making their loan payments right now, the rapidly increasing amount of debt farmers are taking on to deal with depressed prices is concerning, especially for smaller operations.

“It seems like the larger producers, you think about their equipment and everything else, they’ve got some added advantages,” Barker said. “It doesn’t mean the smaller producer is necessarily ‘out,’ but I do think they got more challenges in this current environment.”

U.S. Department of Agriculture economists predict nationwide farm debt will reach $263.7 billion in 2019, levels of debt not seen since the 1980s farm crisis, when thousands of farm families defaulted on their loans amidst a trade embargo with the Soviet Union and high loan interest rates.

New Farmers

Tom McConnell leads the Small Farm Center at West Virginia University’s Extension Service and tries to help small farms succeed, in a state that has the highest proportion of small farms in the nation. He’s lived through the 1980s farm crisis and saw many dairy and beef farmers lose their farms.

He said one solution for small farmers to withstand these depressed prices is to switch to crops that bring a higher value, like vegetables. But those can be more labor-intensive, and the transition can be difficult.

“If you’ve been in a family that has milked cows or grown row crops for three generations, and I suggest you grow three acres of sweet corn and five acres of snap beans, there will be some resistance to that,” McConnell said.

McConnell said it might take a new generation to redefine what a successful small farmer business model can look like.

One of those younger small farmers is Joseph Monroe, who moved from Indiana to central Kentucky to raise beef cattle and grow tomatoes and greens. Monroe believes a way forward for smaller farms is to find ways to work together to sell products and have a greater market impact.

“I think there needs to be some pioneers and some examples out there of how to draw up a contract to work together,” Monroe said. “I think we need to throw all the darts and see what hits.”Share on Twitter

This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.