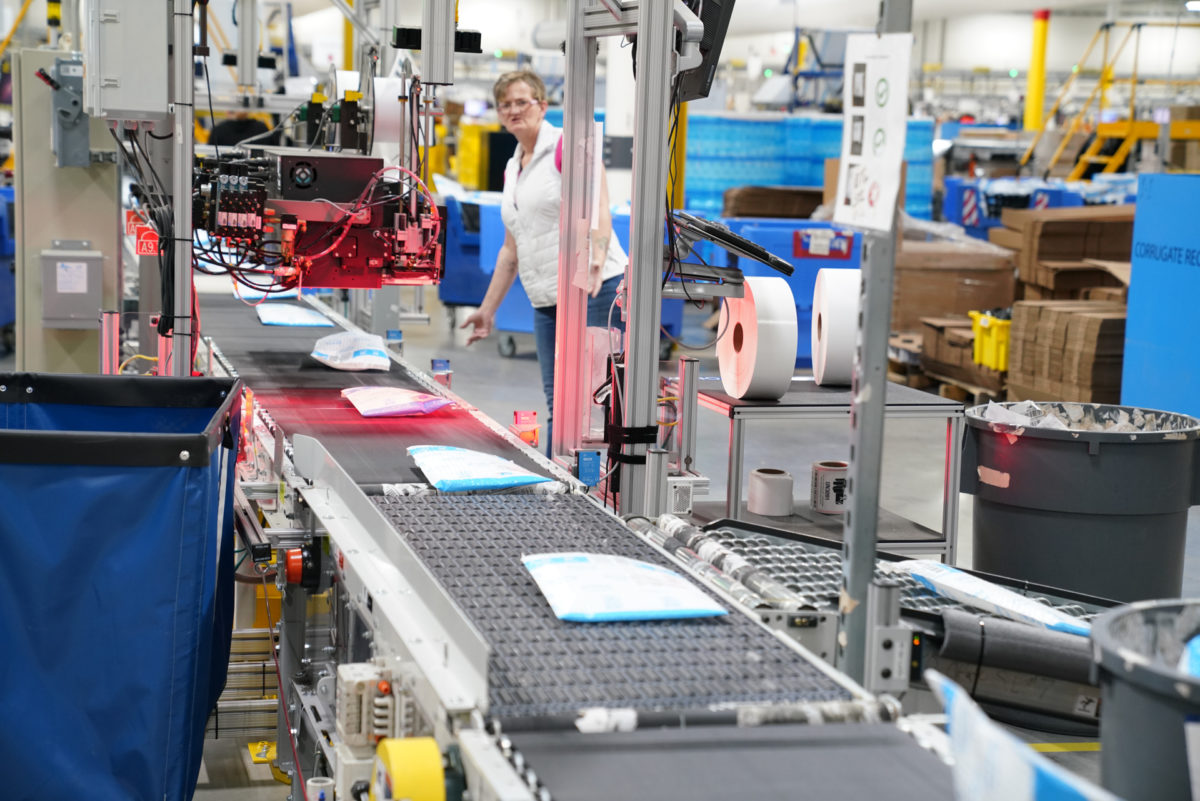

Amazon employee Andre Woodson made his way among yellow bins traveling through a vast warehouse filled with boxes and envelopes to be packed, sorted and shipped. In Amazon-speak, this is a “fulfillment center.”

“Our Jeffersonville, Indiana, fulfillment center is about 1.2 million square feet, which is equivalent to about 28 football fields,” Woodson explained.

About 2,500 people work here. But looking out across the floor it’s sometimes hard to find a human among the boxes, bins and conveyor belts. Often they’re working closely with the machinery. At a packing station an employee is surrounded by boxes and envelopes of different sizes.

“So here at our ergonomic pack stations our great associates interact with the technology to package customers’ orders,” Woodson said as the employee scanned items. A computer shows the optimal box size to be packaged. “The tape machine will push out the perfect amount to tape so they can seal the box,” he said.

There are about 20 Amazon fulfillment and distribution centers like this in Kentucky and Ohio. Some are the host town’s main employer. About 20 percent of the workforce in Campbellsville, Kentucky, for example, works at Amazon. UPS and other product delivery services have a large presence in the region as well, and all are likely to make more use of automation.

“We have a lot of what we call ‘pick and pack’ warehouse facilities and those facilities have a lot of people in them, but they also have a lot of computers and robots,” Michael Gritton said. He’s executive director atKentuckianaWorks, a nonprofit organization focused on workforce development in Kentucky and Indiana.

“Over time you would expect those facilities to have fewer people and more computers and robots,” Gritton continued.

The Ohio Valley has seen its workforce disrupted from the decline in the coal industry and globalized trade’s effects on manufacturing. Automation is again changing the way we work and is predicted to lead to more disruptions.

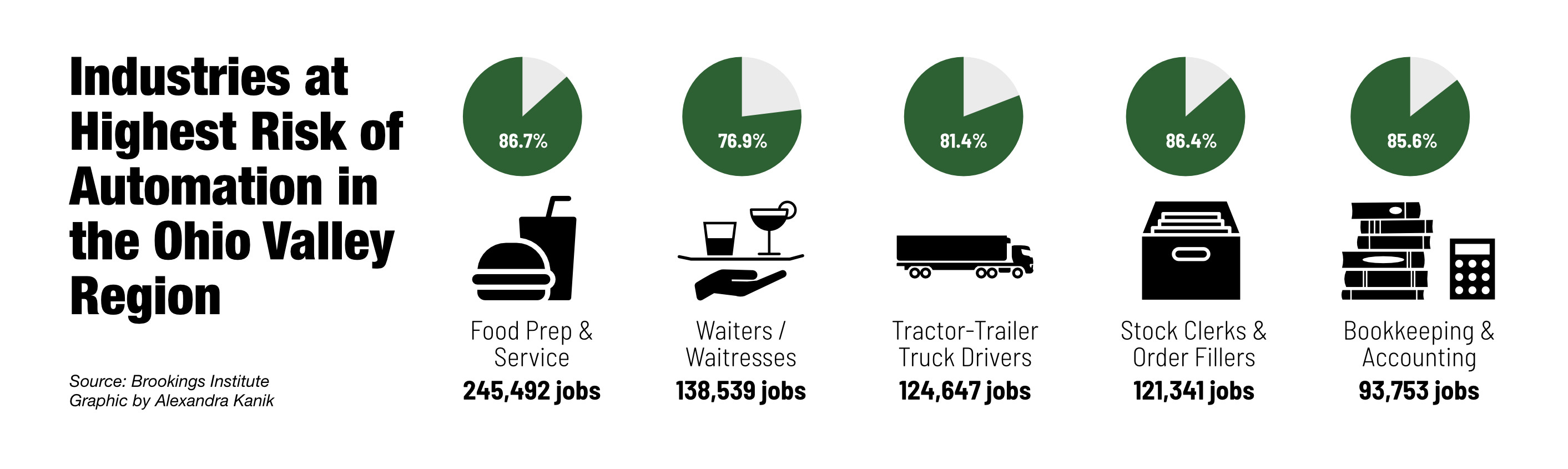

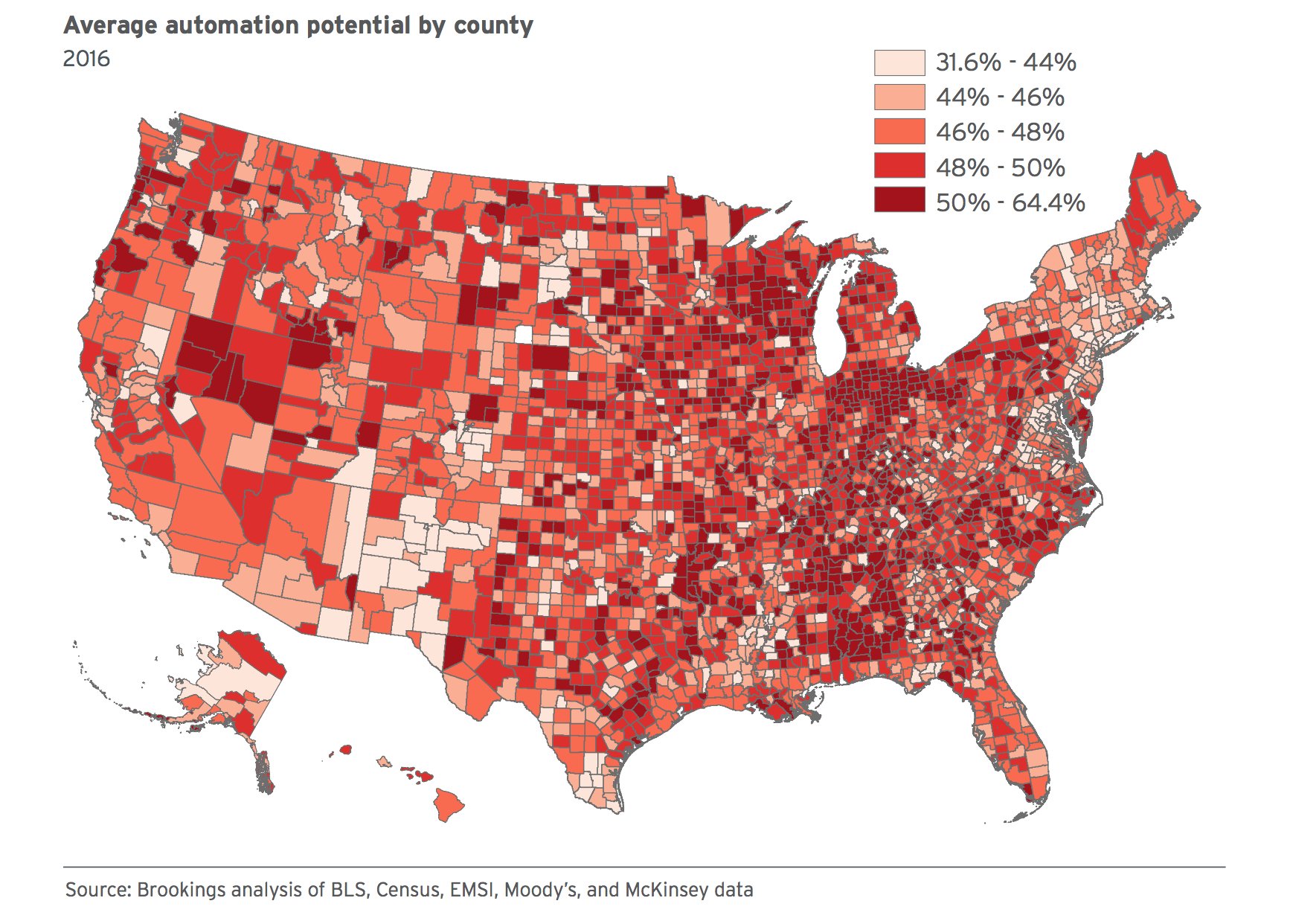

That has planners like Gritton concerned about what rapid automation could bring, and it’s not just the warehouse workers at risk. A recent Brookings Institution report showed about one-quarter of all jobs in the Ohio Valley region have a high chance of being wiped out by automation, with service jobs, truck drivers, and office administrators among the most vulnerable. That could lead to disruptions in employment and greater income disparity.

Growing Gap

The Brookings report ranked states according to the proportion of their workforce deemed vulnerable to dislocation. Indiana and Kentucky are ranked first and second, respectively. (Ohio comes in 13th and West Virginia is 16th.)

Gritton worries that disruption could result in more people moving to the bottom of the earning scale, further exacerbating income disparities. A graph showing the income and job distribution would begin to look like what he described as a barbell, with low-wage workers at one end and “a few, big super-winners, and not much in the middle.”

More people could become reliant on jobs that involve irregular schedules and lower pay. “That doesn’t seem to be a recipe for a happy Kentucky, a happy Louisville or a happy America,” he said. “So that’s the conversation the country’s going to be having about this change as it happens.”

Gritton said education is going to be key in adjusting to changes in the workforce. He said government leaders need smarter strategies to invest in people more than one time in their lives.

“We’re trying to work to help people reskill and retool where they can,” he said, but noted that the demand for that is beginning to look daunting.

“There are going to be more and more people we’re going to run into who are going to be asking for this opportunity to upskill, to move their skill levels up to make them marketable in an economy that’s going to be demanding that. But I think it’s a big open question, who pays for that?”

Constant Learning

Mark Muro is the lead author of the Brookings report, which does more than just point out potential problems. The report also showed that education can make places and people better able to adapt.

“We call it promoting a constant learning mindset, but it can’t simply be the responsibility only of the workers,” Muro said. “The whole system has got to change.”

Muro said the way the education system is set up now doesn’t encourage lifelong learning and the constant development of new skills.

He said people need affordable ways to develop the skills that are uniquely human by investing time into becoming creative problem solvers and developing interpersonal skills.

“Get better at being human,” he said. “What we should not do is try to compete with the robots because they will always do a better job at basic rote tasks.”

Muro said the places with higher levels of degree attainment will have the least amount of exposure to automation. The Ohio Valley is at a higher risk because of the share of workers in agriculture, small factories and the service industry. But Muro said because the Ohio Valley region is mostly rural, it may have more time to adjust to these rapid shifts and prepare people for change.

“The technological possibility doesn’t mean reality and there is likely to be a time delay,” he said. “Which may be a time for the region to buy itself time and begin thinking about retraining some of its workers to make sure they’re in the most resilient and promising fields.”

Muro said it’s important to understand that new technologies will be able to do a lot of different tasks but not whole jobs. He said that means entire jobs or fields won’t be suddenly replaced by robots.

“It’s not like this has created an epidemic of joblessness and done away with wholesale employment, that’s simply a misnomer,” he explained.

The Brookings report looks at what it calls the Information Technology Era. When machines handle routine activities, it frees up the human capacity to create new products and tasks. For example, the report notes that the increase in consumer banking services was occurring as ATM machines were replacing some tasks bankers did.

Bargaining Power

Not everyone sees automation as the great threat some predict. Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. He recommends a more nuanced view that emphasizes job quality over quantity.

“Try to understand less the extent to which technology is going to displace workers, because that’s actually pretty unknowable, and more thinking about its impact on the quality of jobs,” he said.

Bernstein said the problem with the argument that robots are coming to take jobs is that the country is creating about 240,000 jobs a month and unemployment is low.

“I don’t mean everything is fine by a long shot, but I think people face a lot of economic challenges that don’t have all that much to do with automation and have a lot to do with just their personally weak bargaining power,” he said.

Bernstein said automation has changed jobs for those who have reskilled and made themselves complementary to the machines. He said it’s the responsibility of the government to push companies like Amazon in the right direction.

“Left to their own devices private companies would never invest enough to help workers make a transition because it’s not in their interest,” he said. “They can’t profit if they teach you to be more productive in a different industry or a different job.”

However, Bernstein warned, the government’s track record for preparing workers for these type of transitions is not good enough.

Rapid Change

Jane Oates agrees that automation and technology have always led to disruptions in the workforce. The difference this time, she said, is the pace of that change. Oates is the President of Working Nation, a national nonprofitfocused on what it calls the looming unemployment crisis. She said people need to understand that every sector is changing and those who aren’t willing to make changes to become lifelong learners are going to be left behind.

“We as a country had 140 years to move from an agricultural society to an industrial society,” Oates said. ”We could adapt to anything with that kind of warning time, but now things are changing over a weekend.”

Oates agrees with Bernstein that employers should be responsible for preparing the future workforce and she said there’s a way the government can reward workplaces that do.

“When you allow federal dollars to be spent for incumbent worker training, that sends a clear message that if an employer wants to do the right thing there are government dollars that could assist there,” she said.

That sort of proactive policy could be the difference as automation changes the workforce. Without it, it’s possible that a place like the Ohio Valley could be left further behind.

This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.