Grundy County, Tennessee, ranks near the bottom of the state in the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. But that hasn’t stopped the small county from initiating a top-tier response to improving community health. In the new rankings released today, the county improves its position from a last-place 95th to 93rd.

It’s lunchtime at Sam’s Corner restaurant in Coalmont, Tennessee. Conversation wafts around the room, along with the aroma of freshly baked cornbread and vegetable soup.

Red-checked oilcloths cover the tables, which surround a pot-bellied stove. A group of six women is gathered at one of the larger tables, conversing while they await their orders.

When the steaming food arrives, the talk slows a bit, but it doesn’t stop. The subject: how to improve community health. And in Grundy County, Tennessee, that means there’s a lot to talk about.

“It all goes back to what my mom and dad said,” says Emily Partin, one of women at the large table, referring to efforts to address the county’s difficult health issues. “You have to bloom where you’re planted.”

That’s not always easy. Last year rural Grundy County ranked last in Tennessee in its “health outcomes” in the annual County Health Rankings and Roadmaps report. There are signs of change. In this year’s rankings, released today, Grundy County moves up two position in its health outcomes, from 95 (last place in the state) to 93.

But at the lunch table, two months before the release of the new report, the women aren’t focused on their position on the list. (“For us to move up, someone else has to move down,” Partin says. “And we don’t’ want to wish that on anybody.”) But they are focused on improving their residents’ health.

They have a lot to show for it:

- Smoking cessation programs.

- School-based behavioral telehealth.

- Parent training and support.

- An invigorated nonprofit sector.

- Improvements in the child-welfare care system.

- University partnerships.

- Community-wide fitness initiatives like a walking challenge.

- And mile after mile of trails with stunning views, and more.

The programs have grown from local leadership, with outside technical assistance and funding at key points along the way.

So how does a county that lies near the bottom in Tennessee’s health rankings create a top-tier effort to change?

Where to Start?

Partin grew up in Grundy County and moved away for college and a career as a licensed professional counselor. She grew up in Tracy City, a town of about 1,300, which, like most of Grundy County, lies atop the Cumberland Plateau. The plateau offers million-dollar views of the Tennessee Valley but little economic opportunity, especially since the coal-mining industry pulled out in the 1980s. Partin left home about the time the last of the coal did. “I thought I was never to return,” she said.

But family ties mattered. After 20 years away, she went back to care for her father. She thought she’d stay about six months. That was 19 years ago. Partin got a job as the Grundy County Schools family resource center director and got re-involved inthe community.

As a young person, Parton attended Grundy County’s single high school, then located on the southern end of the county in Tracy City. The sturdy, two-story brick structure from the 1930s was a source of community identity and pride, Partin said. In the 1990s, the board of education built a new school.

“One day they just told the students, ‘Pick up your stuff and we’re leaving,’” she said. “And they picked up their books and they left everything just like it was. It was like a ghost town.”

The building sat vacant for years. A community group used the auditorium as a movie theater until they could no longer get movies in film format. Without the funds to purchase a digital projector, the theater shut down. Sports teams sometimes practiced in the gym, and occasional fitness classes were held there. Otherwise, the school building sat empty – its red-brick edifice a reminder of its former importance.

After an unsuccessful effort to convert the building to a trade school, Partin and others came up with the idea of turning the old school into a one-stop shop for a variety of family and community services: the school’s family resource center, a primary medical care office, mental health services, nutrition assistance, financial management classes, community college courses, and other programs. “Anything that would get someone on their feet and able to work and provide for their family,” Partin said. Several agencies have supported the renovation, with the Southeast Tennessee Development District helping facilitate the funding effort, Partin said.

The building’s history makes it an ideal setting for a community-services center. “When families are needing help, if there is one place that would feel inviting, it would be that building,” Partin said.

A committee of volunteers got to work, but the pace of progress was slow at times. The size of the steering committee began to shrink. The attrition concerned Partin until she realized the volunteers weren’t quitting; they were just moving on to new work.

“The people who were dropping off weren’t just dropping off the face of the earth,” she said. “They were starting something else.” What had felt like decline was a step forward. “You just have to trust people,” Partin said.

Community Philanthropy

That trust turned out to be well placed. At roughly the same time that Partin and others began planning the school renovation, other initiatives got underway, including an effort to create a community foundation.

When it came to formal philanthropy, Grundy County was not on the map. That changed with the 2012 establishment of South Cumberland Community Fund, which serves the plateau portions of Grundy, Franklin and Marion counties.

“Previously, there were no local philanthropic resources,” said Jack Murrah, an early proponent of the foundation. A resident of Monteagle, Murrah moved to Grundy County after a career at the Lyndhurst Foundation in Chattanooga.

With professional expertise and community contacts, volunteers found ways to tap community wealth. The University of the South at Sewanee, a liberal arts college located on the plateau a few miles from Grundy County, played a big role, Murrah said. Early support also came from second-home owners and residents who moved to the area for its natural amenities. A major challenge grant from one the county’s second-home owners, Howell Adams, got the operation off the ground, and the community met the fundraising challenge.

Since 2012 the South Cumberland Community Fund has awarded more than a half million dollars for community-minded projects to 45 different organizations.

The organization provides more than money, Murrah said. “[The fund] supports the nonprofit sector with technical assistance and training,” he said. “They have helped with capacity building and building a network within the nonprofit sector.” The foundation also sponsors training, such as courses through Nashville’s Center for Nonprofit Management.

“I think we’ve added some energy to the efforts of a lot of different groups,” Murrah said.

Town and Gown

The University of the South has a long history of involvement with communities on the Cumberland Plateau. But the institution began to take on new roles after the 2010 arrival of Vice Chancellor John M. McCardell Jr. and his wife, child education advocate Bonnie Greenwald McCardell. Besides helping start and sustain the community foundation, the school also established the Office of Civic Engagement, which connects the university directly to local agencies.

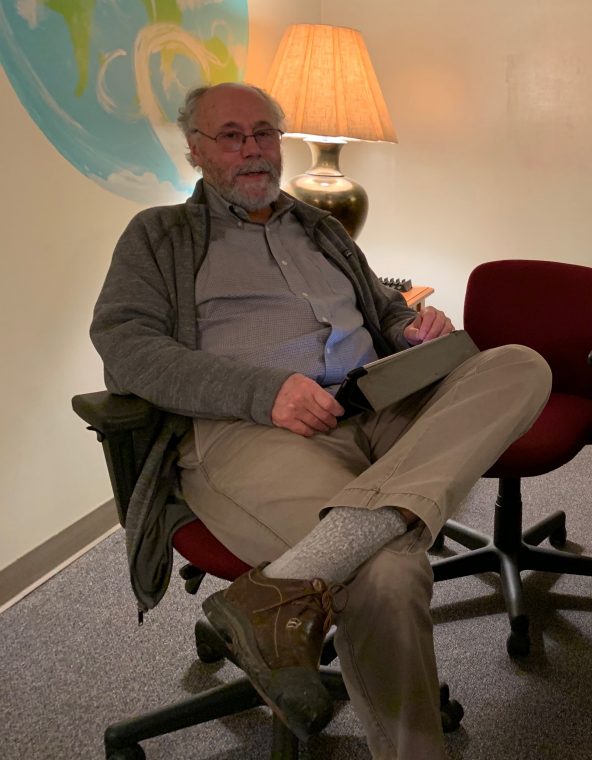

The program takes its cues from local institutions, many of which are working on health-related issues, said Jim Peterman, a philosophy professor who also heads the Civic Engagement Office.

“Our orientation for working in the community, right from the outset, was not the traditional service model,” Peterman said. “It has been to work in communities in ways that build capacity for them to achieve their own aspirations.”

The office facilitates student internships, community-focused research, and an AmeriCorps VISTA program with local agencies, among other activities.

“The work that we are doing will emerge out of relationships,” Peterman said. “We don’t know for sure what that is going to be ahead of time.” That’s a different way of working for the 150-year-old Episcopal institution.

Sewanee’s alumni connections have also come into play. Partnerships focused on child development with Yale University are one result. Another recent alumnus stayed in the area after graduation to create a personal loan institution to compete with less consumer-friendly payday lenders.

Middle Tennessee State University staff have also been active in Grundy County. Vickie Harden, an assistant professor in social work at the school in Murfreesboro, has arranged internships and research and secured grant funding for projects in the county. She got to know the county while working for Volunteer Behavioral Health, a nonprofit mental health agency.

Harden and Sheila Beard, who also worked for Volunteer Behavioral Health at the time, wrote a federal grant proposal to help organize communities on the plateau around healthcare needs. Beard is now the mental health liaison for Head Start and serves on the South Cumberland Community Fund Board.

Harden said it’s important for higher education to get involved in health-related projects because they can provide resources and link local people to bigger issues. “I think there’s an opportunity there to not just bring in manpower but bring in thought leadership,” Harden said. “[We can] possibly bring in folks who can look at federal and state policies and be able to articulate what’s happening on the ground to policy makers.”

Hit the Trail

One indicator of health is residents’ access to recreational facilities. Grundy County residents see progress on this front. The Mountain Goat Trail Alliance, for example, is converting an old railroad right of way into recreational trails.

Completed portions of the project include a 3.5 mile-section that runs through Tracy City and a longer section that runs through Monteagle to Sewanee. Construction is scheduled to begin in the fall of 2019 on three more miles that will connect the two segments.

It’s not easy to convince people who live in an economically distressed area that trails are the best use of public investment, Partin said. But there’s a direct link to improving community health. “We see that as part of the built environment that’s going to help address some of our health disparities,” she said. “Even though you are a rural county and there are lots of grassy areas, there’s really no place for families to get together and get exercise like pushing a baby stroller.”

Only a third of Grundy County residents say they have access to exercise opportunities, such as walking trails.

With easily accessible and family-friendly trails, walking is much more practical, Partin said. Local people have started competing in a national walking challenge. Partin’s church, Tracy City First United Methodist, had about 60 people sign up for the challenge last year. Together they logged about 11,000 miles and engaged in friendly competition with other groups. They expect a similar turnout for this year’s challenge.

And the Mountain Goat Trail keeps growing. Grundy County government acquired 17 more miles of railroad right of way in 2018. That will extend the trail all the way to Palmer, a former coal camp that lies just a mile or two from Savage Gulf State Natural Area.

The Great Outdoors

Old railroad beds make for smooth, well graded trails. Savage Gulf State Natural Area offers the other kind. Savage Gulf is part of South Cumberland State Park, a non-contiguous holding of 31,000 acres covering 10 units in four counties. It’s the largest park in the Tennessee system. Besides Savage Gulf, the park includes iconic features of the Cumberland Plateau – gorges, waterfalls, sandstone cliffs. The park’s trails range from multi-day backpacking scrambles to short strolls on paved, wheel-chair accessible walkways.

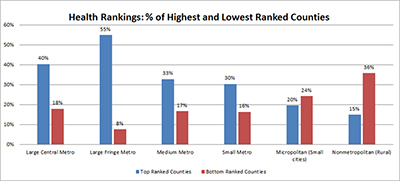

County leaders know Grundy’s natural assets could create jobs and businesses based on the recreation economy. Rural counties with good recreational amenities tend to retain more population and perform better economically than other rural counties, studies show. (Read about one of those studies

in the Daily Yonder.) Tapping the economic potential takes time, however. For example, there are few tourist accommodations outside Monteagle. Some families are starting to supplement their incomes with short-term rentals through services like AirBnB. (This type of economic activity requires internet access. The county has access through a telephone cooperative and four for-profit providers. National industry reports, which are widely criticized for inaccuracy, say Grundy County access speeds range from 5 Mbps to 1 Gbps.)

Although Partin worries that the service-industry jobs that come with recreation won’t pay enough to significantly improve family economic conditions, there aren’t a lot of other options. Coal employment – the county’s former economic underpinning – has been gone for more than a generation. A common side business, chicken farming, faded when the industry demanded that farmers get big or get out. Today, people may make some money selling their second-growth timber, and small clear cuts are numerous throughout the county.

Partin said finding jobs that pay better requires driving “off the mountain.” (Locals refer to areas not atop the plateau as “off the mountain.”) Some go to Chattanooga, about an hour’s drive each way. A little farther in the other direction lies Murfreesboro, with a Nissan plant, Veterans hospital, and an Amazon fulfillment center. Either direction, the commute includes descending and ascending the 1,300-foot escarpment at the beginning and end of the day. That results in Grundy County residents having above-average commute times, another measurement used in the health rankings.

But the recreation economy is having an impact on local business. One establishment that has made the transition from the coal-town era to a more tourist-oriented economy is the Dutch Maid Bakery in Tracy City. The bakery was founded by Swiss immigrants in 1904. Their first customers were the coal-town residents, many of whom had also immigrated from Switzerland. Today, the bakery still serves locals. But they also have a customer base among campers and second-home owners, according to a video produced by Bake Magazine.

Families First

Another set of community efforts has addressed parenting and children. Grundy County was the first rural site (and just the second in the entire state) to create a safe-babies court team. The program works with parents who have entered the child-welfare judicial process with a child 3 years old or younger. Rather than taking a merely judicial approach, advocates help families gain access to programs that can improve conditions at home.

The safe-baby program manages short-term family crises while aiming for long-term impact, said Katie Goforth, who manages the AmeriCorps VISTA project at the University of the South.

“In baby court, even though our focus is on that baby and that family, there’s an even bigger chance that the next baby being born into that family is going to get the benefits of the energy, time, and resources we’ve put into that family,” said Goforth, whose background is in behavioral health.

For other parents, Partin has started Discover Together. She calls the program a “place-based family co-op for families with children from birth to 5 years old.” Twenty families are participating. They gather twice a week for two to three hours for multi-age activities that mix toddlers, preschoolers, and parents. The multi-age mixing can surprise people.

“That mother may say, ‘Well, my 6 month old is not going to sit there and listen to that book being read,’” Partin said. “But guess what? In three or four weeks, guess who’s crawling over to be right in the middle of the 4 year olds?”

The long-term goal is for parents in the program to share what they learn. “We are hoping that they are going to become the ambassadors that take the information out to others,” Partin said.

But Wait, There’s More

Several other noteworthy community health initiatives are underway, many of them supported by VISTA workers sponsored through the University of the South and the South Cumberland Community Fund. There’s a health ambassadors program that will work through church members to do peer health education, a healthy-cooking program for families that participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, a faith-based housing improvement mission called Mountain T.O.P., a state-mandated County Health Council that brings together officials from different agencies around the county to share information. And some efforts have sprung up from families that simply want to give something back to the community. One couple who work in healthcare professions, for example, volunteers their time to teach community courses in managing type 2 diabetes. And, in what must be the most obvious sign that change is afoot, the Smokehouse Lodge and Cabins, a Monteagle restaurant that specializes in barbecue, has added healthy menu choices.

Bottom Line

Despite Grundy County’s improvement in the 2019 rankings, the county remains near the bottom of Tennessee’s 95 counties. So are the programs making a difference?

“What stands out in Grundy County is that they have decided to take action,” said Aliana Havrilla, a community coach with County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. “There’s a core group of people in the community working to improve health outcomes and strengthen the community. And they are reaching out to others to include them in the journey.”

Harden from MTSU agrees that the effort is important. “I see how many people are struggling, but I also see them strengthen that community,” she said. “That’s what has kept people moving forward. … They’ve been in that community for generations and they just don’t give up.”

One More Stop

The first floor of the South Cumberland Learning and Development Center – the one-stop services center that is going into the old Grundy County High School in Tracy City – will be ready for occupancy this fall, Partin said. Renovation is underway on the second floor. Prevent Child Abuse Tennessee, which provides in-home parenting support, and Volunteer Behavior Health have signed letters of intent to use space in the center. Other potential tenants are a primary care clinic and community classes and workshops. Partin hopes community college courses and other educational services will eventually be part of the mix.

On the entertainment front, first-run movies are likely to return to Grundy County. The old school auditorium has a digital projector ready to be installed as soon as the dust settles on the renovation, Partin said.

The old gym, with a hardwood floor still in excellent condition, is next on the list for repairs. The county is using a diabetes prevention grant to help convert the space into a community fitness facility.

In the midst of many inconspicuous changes, the high school project stands out as tangible evidence of change, said Julie Willems Keel, who works in community development initiatives with Mountain T.O.P.

“It’s a real sign of hope – that things can change and progress. Not everything is decaying and falling apart,” she said. “We’re integrating our community’s history with forward progress.”

Disclosure: The County Health Rankings and Roadmaps is a project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Center for Rural Strategies, which publishes the Daily Yonder, receives funding from the foundation.

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.