On the night of July 24, 1916, a natural gas explosion near Cleveland trapped workers in a waterworks tunnel beneath Lake Erie. Rescuers sent in to recover the trapped men were themselves felled by “noxious fumes.”

The Cleveland authorities knew just who to call: Garrett Morgan, an inventor who had recently given a demonstration of his breathing contraption.

Morgan arrived at the scene still wearing his pajamas. With his strange breathing device strapped to his face, Morgan, along with his brother and another brave volunteer, descended into the muddy disaster site.

Finally, Morgan emerged, dragging a barely conscious survivor.

The inventor made a total of four trips that night, according to a biography of Morgan by historian William King. His breathing device saved lives that day, and it led to the gas mask that’s still in use today.

Morgan’s fame spread as a result of the incident. But sales of his device plummeted.

“People were reluctant to use the breathing apparatus, which is what Morgan called it, because there was a discovery that it was produced by an African American,” said John Hardin, a professor emeritus of history at Western Kentucky University.

Even among the work of under-recognized African American inventors like George Washington Carver and George Franklin Grant, Morgan’s inventions stand out not only for their economic success but also for their contributions to public safety.

Morgan’s life spans the years between Emancipation and the Civil Rights Act. Born to formerly enslaved people of limited means, Morgan took bold steps to further his education and excel across multiple disciplines. But his industriousness, his business acumen, and his contributions to the public good could not exempt him from the realities of racism.

Life In Claysville

Morgan was born in 1877 in the segregated African-American hamlet of Claysville, just outside Paris, Kentucky. His parents were formerly enslaved people who had been owned by Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, Hardin said.

Kentucky was a slave state before the Civil War but did not secede from the Union. Both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Union president Abraham Lincoln were born in Kentucky.

After Emancipation, former slave owners looked for a way to keep the formerly enslaved nearby as workers. The solution, according to Sarah Hoskins, a documentary photographer of African-American hamlets, was to provide or sell marginal or undesirable land to black workers.

“You’ll have a community called Fort Spring or Slickaway because it was on a slope, so you couldn’t plant anything there,” Hoskins said.

Claysville was one such hamlet.

Little is known about Morgan’s early life in Claysville. Hoskins said much of the history of communities like it has also been lost, largely because the communities’ residents were marginalized and mainstream historical discourse ignored black history. Hoskins said elderly residents who remain remember encounters with the Ku Klux Klan and abuse by white police officers.

Historian John Hardin said communities like Claysville would typically have a church or two, maybe a general store among the scattered homes. But they afforded a respite from the racism people faced outside the community boundaries. “They would make life enjoyable or survivable given the fact that law said that you were a second-class citizen,” he said.

An Inventive Mind

Perhaps recognizing that his options were limited in Kentucky, by the age of 14, in 1891, Morgan had left home for Cincinnati and then Cleveland, Ohio, to pursue a better future.

“Garrett Morgan was one of those individuals who believed in the American dream of making a life for yourself. But he had to move out of Kentucky to do it,” Hardin said.

Morgan’s granddaughter, Sandra Morgan, told Popular Mechanics that Morgan’s marriage to a white woman, Mary Hassek, cost him his job as a sewing machine mechanic. But he took the skills he learned and opened his own sewing machine and shoe repair shop in 1907. He used devices of his own making to set himself apart.

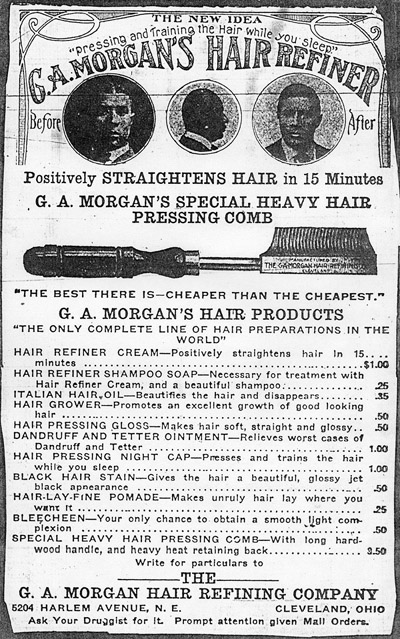

From tinkering with his machines, Morgan discovered that a substance that kept sewing machine needles from overheating also straightened hair. He incorporated in 1913 the G. A. Morgan Hair Refining Company, which sold hair products for the black community.

“Segregation, in all of its dimensions, forced the black community to work together,” Hardin said. “You had to use the community’s support to enable you to become successful, and when you did that and you were successful, then you helped to pull others up.”

The financial security he gained from the hair product company gave Morgan the space to pursue grander inventions. His gas-mask predecessor, patented in 1914, supplied the wearer about 20 minutes of breathable air kept in a bag strung at the waist. It was quickly the favorite among fire chiefs from Akron, Ohio, to Yonkers, New York, historian King wrote in his 1985 biography of Morgan.

Morgan became wealthy enough to own an automobile, a rarity at that time, particularly for a black man. Cleveland streets were clogged with horse-drawn carriages, bicycles, pedestrians and automobiles.

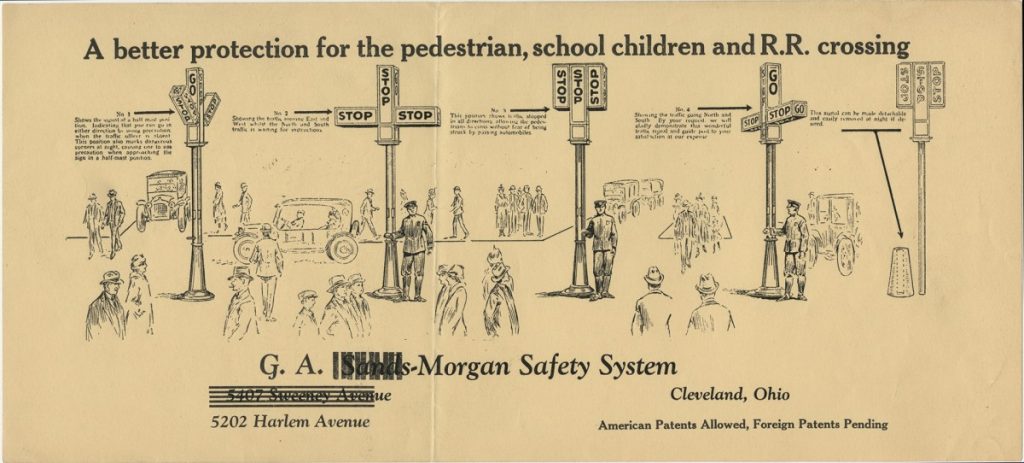

His experience witnessing a terrible accident inspired his most successful invention. Traffic signals at the time were crude and accidents were common. Morgan realized that a signal with a third position, a slow-down directive, would help with traffic flow.

His set of automatic lights placed at intersections told drivers when to go, when to slow down, and when to stop. That invention, the three-position stoplight, is now ubiquitous around the world.

General Electric paid Morgan $40,000 for rights to the patent.

Public Contributions

In addition to his inventions and business success, Morgan was active in political life in Cleveland and beyond. He started a country club for black Ohioans. He founded the Cleveland Association of Colored Men, which organized events to promote the economic and social success of the city’s black community and later became part of the NAACP.

And the newspaper he launched, the Cleveland Call, was among the country’s most successful African-American papers.

“It’s important to remember people like Garrett Morgan because he demonstrated that despite all of the strictures and and regulations and practices of racial segregation, he persevered,” Hardin said. “Morgan was one of those who believed that progress for himself and the race, the black race, was also progress for the United States of America.”

Garrett Morgan died in 1963, a year before the passage of the Civil Rights Act. But recognition was slow to come in the place of his birth.

In 1972, because of a public housing crisis, the last remaining home in Claysville, Kentucky was demolished. The land where Claysville once stood was renamed Garrett Morgan Place. An elementary school in Lexington was renamed in his honor just a few years ago.

Not far from that school, a statue of John Hunt Morgan, who owned Garrett Morgan’s parents, still stands.

This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.