Just a few months ago, the U.S. coal mining industry was on track for its safest year in history. But in an eleven-day span in late December, three miners died after separate incidents, bringing the total number of fatalities in 2018 to 12, even as coal mining employment continued its decline.

“It is a reminder to enforcement agencies and companies who are responsible for miner safety that you always have to be vigilant, you can never let up your guard,” Kentucky lawyer and mine safety advocate Tony Oppegard said.

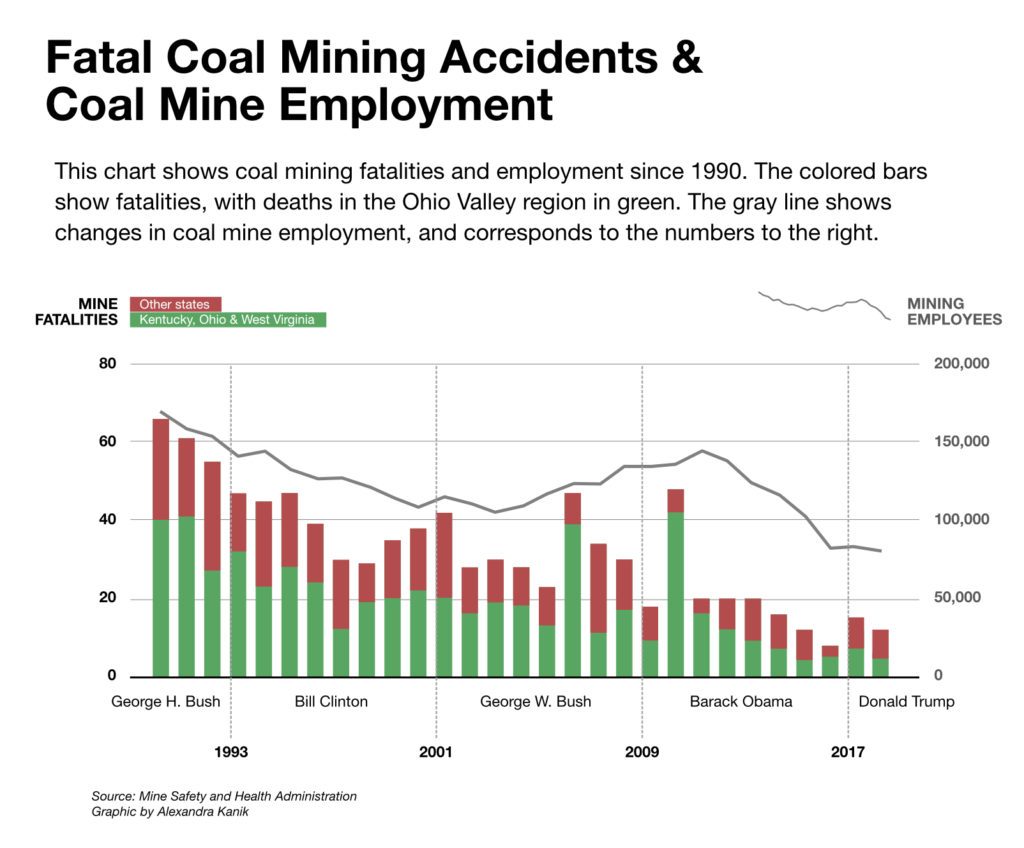

Despite that grim end to 2018, federal mine safety records show the number of fatalities in U.S. coal mines last year tied the second-lowest mark on record. Twelve miners died in 2015. The lowest number of fatalities for a year came in 2016, when 8 miners were killed. Fifteen miners were killed on the job in 2017.

The numbers are low compared to just a little more than a decade ago, when dozens of miners perished year after year. The mining industry and the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, or MSHA, point to improvements in mine safety practices.

However, the number of miners employed was also lower in 2018 than in previous years. Preliminary data from MSHA indicate total coal mine employment in 2018 reached the lowest level in the industry’s modern history. Oppegard said he thinks that is the primary reason for the reduction in deaths.

“I think the low number says more about the decline of the coal industry,” Oppegard said. “Certainly in Appalachia there’s about one-fifth the number of mines that are operating today than were in operation five or six years ago. So I think that’s the major reason.”

A comparison of mining employment and fatalities demonstrates Oppegard’s point. In 2009, for example, the total annual fatalities fell below 20 for the first time in industry history. When 18 miners were killed in that year, the industry employed roughly 134,000, for a death rate of 13.4 per 100,000 workers.

The unofficial employment figures for 2018 show just 80,762 employed by coal operators and contracting companies. That means the death rate for 2018, at 14.8, was slightly higher than in 2009.

Mine safety and health made news in 2018 in other ways that safety advocates found worrisome, as the Trump administration’s leadership at MSHA made controversial decisions and the toll from Appalachia’s epidemic of black lung disease continued to mount.

“Troubling Development”

In December the United Mine Workers of America sued MSHA after the agency reduced its heightened oversight of a West Virginia coal mine with a poor safety record.

The suit has to do with MSHA’s use of its power to declare mines with a history of significant safety violations as having a “Pattern of Violations.” Known as “POV status,” the declaration is an enforcement tool that allows the agency to increase regulatory scrutiny at a mine.

That was the case with the Pocahontas Coal Company’s Affinity mine in southern West Virginia in 2013. Under the Obama administration, MSHA placed Affinity on POV status after two miners were killed in separate incidents within a two-week span.

This year, under the Trump administration, MSHA decided to remove POV status for the Affinity mine in an agreement with the company that resolved litigation on the matter, despite a continued record of spotty safety performance at the mine.

The decision raised questions about MSHA director David Zatezalo’s connectionsto the mining industry. Zatezalo is a former coal company executive who also served on state coal associations involved in litigation against MSHA over its use of POV status.

“That’s a troubling development,” Oppegard said. “It shows me MSHA, under this administration, is willing to give sweetheart deals to coal companies.”

Also in December, an NPR investigation found that the surging epidemic of black lung among Central Appalachian miners had topped 2,000 known cases of the most severe form of the disease.

The incoming Democratic chair of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, Rep. Bobby Scott of Virginia, said he will call hearings on black lung in the new Congress.

“Congress has no choice but to step in and direct MSHA and the mining industry to take timely action,” Scott said in a statement.

MSHA declined to make an official available for an interview for this story.

“Personal Tragedies”

Four of the twelve coal mining fatalities in 2018 took place in mines in West Virginia and three in Pennsylvania. Other fatalities were in Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Washington.

MSHA records show the miners were killed during a range of work in both surface and underground mines, and the incidents included deaths from electrocution, crushing, rock falls, fires, and powered haulage of personnel and materials. In at least two cases miners died in mishaps while riding in the personnel carriers that either flipped or collided with mine equipment.

Oppegard said that even while coal mining employment decreases, each working miner still deserves a safe work environment. He added that while MSHA defines a “mining disaster” as an event that kills five or more, each individual fatality brings personal tragedy.

“Each one of those deaths was a disaster to that family,” he said.

This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.