Smithfield announced last year that it will use covered lagoons and digesters on 90 percent of its hog finishing farms within 10 years, a move that could reduce greenhouse gasses, create renewable energy and open opportunities in the biogas sector.

A man stepped out of the side door of his home in Kenansville and refused to give his name.

“I have to live here,” he said.

“Here” is hog-farming country, where signs reading “Stand up for Farmers” sprout from the roadsides.

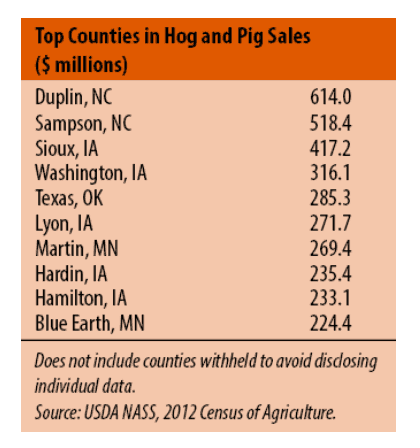

Here, in Duplin County, hogs outnumber people 32-1.

Just outside of view from the man’s home lies Optima KV, a pilot project involving five farms that use covered lagoons and anaerobic digesters to convert methane from hog waste into renewable natural gas. The biogas is then injected into pipelines and sold to Duke Energy.

The man complained about odors and flies from Optiva KV. He said he built his sun porch for that reason. But he admitted that the smells aren’t as bad as they once were, before the covered digesters were installed.

Optima KV could be viewed as a microcosm of the not-too-distant future, a time when almost all of Smithfield Foods’ hog finishing farms in North Carolina will use covered lagoons and digesters to convert methane into biogas.

Smithfield announced in late October that 90 percent of the lagoons on those farms will be covered within 10 years. Similar projects will also be done in Missouri and Utah.

The announcement was followed by another one a month later in which Smithfield said it was partnering with Dominion Energy, a public utility based in Virginia, to spend at least $250 million in the next decade on hog farms in North Carolina, Virginia and Utah.

Smithfield says it is taking the steps partly to meet its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 25 percent by 2025 by capturing 85,000 tons of methane each year to generate renewable natural gas. That’s the equivalent of removing 900,000 cars from the roads.

Smithfield spokeswoman Lisa Martin said the pork producer and Dominion Energy will pay for the infrastructure, including piping, transportation, gas cleaning and equipment to inject the gas into pipelines. Farmers will pay for the digesters and lagoon covers if they choose to participate, Martin said

Biogas could lead to thousands of jobs

Supporters of the project say it will open the door to a fledgling biogas industry in North Carolina, creating thousands of jobs.

“It’s a really big step, there is no doubt about that,” said Tatjana Vujic, director of biogas strategy for Duke University. “I’m very pleased with this development. It’s going to move the needle on biogas in the state, and I think it’s going to open the door to making use of more of our waste streams,” such as poultry.

Vujic pointed to a 2016 report by the nonprofit American Jobs Project that identified biogas and utility-scale batteries as showing particular promise for economic development in North Carolina.

“With the right policies, utility-scale batteries and biogas can support 19,000 jobs per year through 2030,” the report found.

But some environmental groups say Smithfield’s plans don’t go nearly far enough. They want the company to stop using lagoons and spraying the waste onto adjoining farm fields. That method has led to millions of gallons of hog waste spilling out of the lagoons, most recently during Hurricane Florence. It has also led to concerns about overapplication of nitrogen, runoff into creeks and streams and complaints about odors, flies and related issues.

People living next to hog farms, each of which house thousands of animals, say mist from spraying manure on the fields drifts onto their properties. They worry about health problems from pathogens associated with the waste.

“Biogas technology that doesn’t address water pollution and public health issues associated with industrial-scale hog production is not a complete solution,” said Blakely Hildebrand, a staff attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center. “We need technology that addresses those.”

Reducing greenhouse gases

Some environmental groups argue that Smithfield must begin using new and expensive technology that has been proven to work without harming the environment or the health of its neighbors.

But it’s hard to object to covering the lagoons and adding digesters, strictly from the standpoint of creating renewable biogas and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Smithfield’s plans are backed by the Environmental Defense Fund, which helped the company create its goals for reducing greenhouse gases.

North Carolina is the second-largest pork producer in the United States, home to 2,126 permitted industrial swine operations housing nearly 9 million animals. If all of those farms used covered lagoons and digesters, they could provide enough natural gas to power 140,000 homes.

And they could do that for as little as 6 cents per kilowatt hour, or roughly the same price as solar power, according to a study published in 2013 by Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

At the same time, covered lagoons and digesters would be reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which scientists say causes global warming and has contributed to diminished Arctic sea ice, rising ocean levels, flooding from more intense storms and bigger and more frequent forest fires.

“Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth,” the National Climate Assessment warned in a study released in November.

Carbon dioxide is the most common form of greenhouse gas, 200 times more prevalent in the atmosphere than methane. But methane is at least 21 times as potent as carbon dioxide, and its levels have been growing. Agriculture contributes 9 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.

Joint venture

Besides covering lagoons and adding digesters, the joint venture between Smithfield and Dominion Energy also calls for expanding the Optima KV pilot project to two larger farm clusters, in Duplin and Sampson counties. Construction was to begin before the end of 2018.

“Our companies recognize the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the future of our planet,” Thomas Farrell, Dominion’s chairman and chief executive, said in a news release. Renewable natural gas “is an innovative and proven way to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture industry by converting it into clean renewable energy.”

Maggie Monast, senior manager of economic incentives and agricultural sustainability for the Environmental Defense Fund, is optimistic about the plans.

“Overall, I think it’s long overdue and much-needed progress,” Monast said. “We haven’t seen progress in a long time on this issue, and I think this creates momentum that we can harvest.’’

Randy Wheeless, a spokesman for Duke Energy, welcomes the initiative, too, but he said biogas has a long way to go before making a significant contribution to the state’s energy needs.

“I don’t think it will be a large contributor to an overall energy mix unless the technology improves greatly,” he said.

Nevertheless, Wheeless believes Smithfield’s plans will transform a small but growing waste-to-energy industry in North Carolina.

“I think it’s put biogas on the radar in North Carolina as a very viable way to create electricity,” Wheeless said.

Optima KV leading the way

North Carolina got its first good look at the potential for biogas from the hog industry in 2011 on Loyd Ray Farms in Yadkinville, about 25 miles west of Winston-Salem.

That year, construction of a covered anaerobic digester system was completed on the farm as a demonstration project overseen and partly funded by Duke University, Google and Duke Energy. The $1.2 million project captures methane from hog waste and uses it to produce renewable electricity.

Using a 65-kilowatt microturbine, the system generates enough electricity to power itself and about half of the farm. Any extra electricity is sold to Duke Energy.

Two years after the project began, Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions published its study that found that the barebones cost of producing electricity from swine biogas could be as little as 6 cents per kilowatt hour.

The researchers also determined that the most cost-effective approach was either to create electricity on a single farm, such as Loyd Ray Farms, or use a cluster of farms to refine the waste into natural gas and then inject it directly into natural gas pipelines. They determined that the best cluster of farms was in an area covering Sampson and Duplin counties, where most of the state’s hogs are raised.

In 2016, Duke Energy entered into an agreement with OptimaBio, the company that oversees the Optima KV project on the five Duplin County hog farms in Kenansville. Combined, the farms raise more than 60,000 hogs for Smithfield Foods.

Under the agreement, OptimaBio will convert swine biogas from the five farms into renewable natural gas and inject it into a pipeline owned by Piedmont Natural Gas. Duke will then use the natural gas to generate electricity. The project is expected to produce enough renewable natural gas to power about 1,000 homes.

Optima KV is the first project in North Carolina to directly inject refined swine biogas into a natural gas pipeline, said Mark Maloney, OptimaBio’s founder and chief executive.

The five farms began injecting the gas into pipelines in March, Maloney said. The project became fully operational in June, with what Maloney called some hiccups in technology along the way.

“Like anything, when you do it for the first time it takes longer than you would hope, but it’s getting easier,” he said.

Other benefits of covers and digesters

An anaerobic digester is essentially a big, air-tight chamber that sits either beside or under a covered hog lagoon. Hog manure is pumped into the chamber, which is heated to spur communities of microorganisms to rapidly eat the waste and convert it into methane, which is trapped under the lagoon covers, siphoned off, cleaned and converted to natural gas.

Smithfield and Maloney point to other advantages of covered lagoons and digesters, besides creating reusable biogas and reducing greenhouse gases. They say the covers will significantly lessen the chances that the lagoons will overtop their banks during major storms.

And Maloney estimates that the covers have reduced odors at Optima KV by 20 percent to 40 percent. While the Optima KV farms still use uncovered lagoons, Maloney said, those with covered digesters receive only fresh manure, where much of the smells come from.

John Kilpatrick owns three farms that are part of the Optima KV project. He agreed that the covered lagoons and digesters have substantially reduced the smells coming from his farms. The digesters also greatly reduce the sludge at the bottom of his lagoons, he said, all but eliminating the expensive costs of hauling it away.

Kilpatrick said he and another farmer have invested about $11 million into the Optima KV project. Kilpatrick said he took out a 10-year loan for his part of the investment and expects to pay it off in five years. He said he makes up to a 15 percent profit on the sale of the methane, above the cost of the loan.

“It’s not that much money when you term it out,” he said. “It should pay for itself within 10 years.”

Whether other farmers will agree to such a large investment to cover their lagoons and digesters remains to be seen.

Martin, the Smithfield spokeswoman, did not provide a cost, other than to say it would be substantial.

“Farmers will have the opportunity to invest in covers or covered digesters,” Martin said, adding that participating farmers will profit from the sale of the natural gas.

“Farmers, I think, are supportive,” Maloney said. “They see it as being good shepherds of the industry, and i think they also see it as a new agricultural commodity.”

Martin also did not say how many of the state’s hog waste lagoons may be converted into covered digesters.

“At this point, it is premature to provide a figure quantifying the number of lagoons involved, as the number of lagoons per farm vary,” she said. “This is why our commitment is based off the number of hog finishing spaces. That being said, it is fair to say that many hundreds of farms will be involved in this effort.”

Angie Maier, the N.C. Pork Council’s director of government affairs and sustainability, noted that the value of renewable energy has increased substantially recently, driven in part by California’s quest to offset its carbon footprint.

“It doesn’t work for everyone, but folks who want to do it and it works for their farms, I think there are opportunities to cover their costs,” Maier said.

Greg Barnes retired in 2018 from The Fayetteville Observer, where he worked as senior reporter, editor, columnist and reporter for more than 30 years.

This story was originally published in North Carolina Health News .