This is the second story in a two-part series about the sale of North Carolina’s Mission Health to the national HCA Healthcare. Read the first part of the series here.

As North Carolina’s attorney general deliberates over whether to approve the sale of the nonprofit Mission Health System to for-profit Nashville, Tennessee-based HCA, a citizens group is asking that, if approved, the deal ensure they have a voice in the future of health care services in their rural communities.

The Mission system covers 18 mostly rural Western North Carolina counties. Its flagship hospital is in the region’s largest city, Asheville (population 90,000). The system also owns five smaller hospitals in the surrounding rural region, which lies in the southern range of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

One of those hospitals is Blue Ridge Regional in Spruce Pine, an hour’s drive northeast of Asheville. The town of 2,100 is located near the Blue Ridge Parkway, about 14 miles northeast of Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak in the Eastern United States.

Susan Larson is a Spruce Pine resident and a member of Sustaining Essential and Rural Community Healthcare, or SEARCH, which was formed last year when labor and delivery services were discontinued at Blue Ridge.

Like a number of her neighbors throughout the region, Larson is anxious about the future of rural health care services. The asset purchase agreement for the proposed Mission sale stipulates that a $1.5 billion foundation, the Dogwood Health Trust, will manage the proceeds and will use social determinants of health to improve the health and well-being of the communities the system serves.

Larson is concerned that rural communities will be left out of the decision-making process.

“All along, we have said that there are two things we want,” Larson said. “We want our hospitals to be protected, and we want the Dogwood Health Trust to be constituted properly, so that it can indeed serve all 18 counties.”

SEARCH has brought in as a consultant Jay Nixon, former governor and attorney general of Missouri who, while attorney general, challenged HCA in the courts, charging that the corporation had failed to live up to all of its responsibilities. A $160 million settlement was reached.

Nixon’s role is to help advocate for an independent health trust that is “governed now and in the future by a board and communities that will do what’s best for the region.”

“Mission is a nonprofit and has built up a significant value, obviously, as laid out by the transaction that’s on the table now,” Nixon said.

Tax law requires the value of a nonprofit’s assets to remain perpetually nonprofit. When a for-profit health care company buys a nonprofit system, one way to keep the proceeds in the nonprofit realm is to create a health care foundation that supports nonprofit work. That’s the plan for the proceeds from the sale of Mission’s assets.

Having reaped the benefits of a nonprofit, Nixon said, Mission has a responsibility to taxpayers. “It’s the community’s money. It’s the state who provided the nonprofit benefits.”

Selecting the Best

“People in this community have a very long history of feeling that the hospital is ours,” said Jean Hunt, a resident of Yancy County, which is served by Blue Ridge Regional. “We do not consider that hospital Mission’s. We consider it to be ours.” Blue Ridge opened in 1955 with significant help from a community fund drive.

“My biggest concern is that the foundation isn’t independent,” Hunt said.

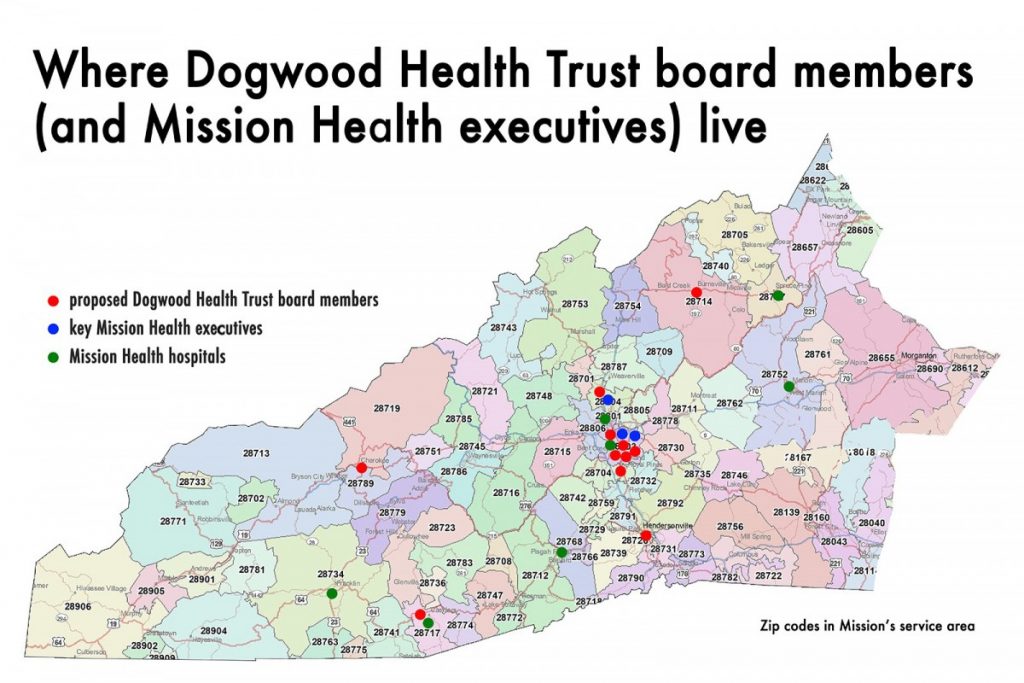

Thus far, nine members of what is proposed to be a 12-to-15-member Dogwood Health Trust board have been appointed. The majority live in Asheville and eight of the nine have current or previous affiliations with Mission.

The health trust “very easily could be the largest per-capita in the country,” said Rowena Buffett Timms, Mission’s senior vice president for government and community relations. “What you want are the very best that you have to offer in your community to begin setting that up.”

Timms has heard the concerns: “People went, ‘Wait a minute, you’ve picked all these people who are or have been on the Mission Health board over the years.’ Absolutely.” Those selected, she said, “have deep pedigree, knowledge of health care, have been intimate with Western North Carolina over the years.”

Hunt agrees that such experience is important: “Obviously, we need people on board with specific skill sets.” She believes those individuals can be found in the rural communities.

As regards Susan Larson’s concern that HCA might close one or more of the regional hospitals, the purchase agreement stipulates that no services will be discontinued for five years and emergency services must be maintained for 10 – unless a hospital’s advisory board approves the discontinuance of a service or the sale or closure of a hospital.

The advisory board at each hospital would have eight members: four appointed by Mission, four by HCA.

‘Three-Comma World’

“I get very concerned about transactions of this nature where you don’t have long-term ironclad guarantees that the facilities and services will remain open,” Nixon said.

“The trust, if it could be what they say it’s going to be, could be incredible,” said SEARCH member Risa Larsen. “I love the sound of that trust.”

Nixon too is big on the potential.

“You have the opportunity to keep this system as it exists now, which obviously is functioning and is gaining in value,” he said. “It’s a vibrant hospital system.”

He envisions the enormous potential of maintaining “all the physical assets and the human capital assets,” then introducing a $1.5 billion-plus foundation. “You really do have great opportunities.”

This transaction, Nixon stressed, is “in three-comma world … a billion dollars. There’s a whole lot of good that can be done if it’s done in a transparent fashion, if it’s done with very solid conflict-of-interest and ethics rules around it and a long-term pipeline of local citizens who understand the particular problems and challenges of the region.”

This story was originally published by the Daily Yonder.