Fifteen minutes before his shift was to end on November 8, 2017, Lariat Rope, a thickset man of 55, tumbled into a pit of scalding water at Sapa Extrusions North America in Phoenix, an aluminum-products plant where he’d worked for more than 25 years. It took rescuers three hours to retrieve his body from the pit, which is used to cool aluminum logs 10 inches in diameter and up to 18 feet long. The cause of death: “multiple trauma due to blunt force injuries, drowning and thermal injury,” according to a report approved by the Industrial Commission of Arizona in April.

The commission’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health, known as ADOSH, cited Sapa for violating a standard requiring employers to install “covers and/or guardrails … to protect personnel from the hazards of open pits, tanks, vats [and] ditches.” It proposed a fine of $7,000 — the amount it had established for violations that “caused or contributed to a fatality” and which, according to the ADOSH field operations manual, cannot be reduced by that agency.

Photo: Courtesy of Evelyn Hinton

Nonetheless, the industrial commission — ADOSH’s overseer — pared the fine to $5,250 “based on [the] employer’s quick abatement” of the hazard, according to a handwritten notation on the April report. “My brother’s life has more value than that,” Rope’s sister, Evelyn Hinton, said in a recent interview, recalling his devotion to their elderly parents. “Five thousand is just not cutting it.” Rope was married and had two sons.

Arizona is among 26 states and two territories (Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) that manage their own worker-safety programs, as they are allowed by law to do — providing the programs are “at least as effective” as the one run for the rest of the country by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Some meet or exceed this threshold; others fall considerably short of it.

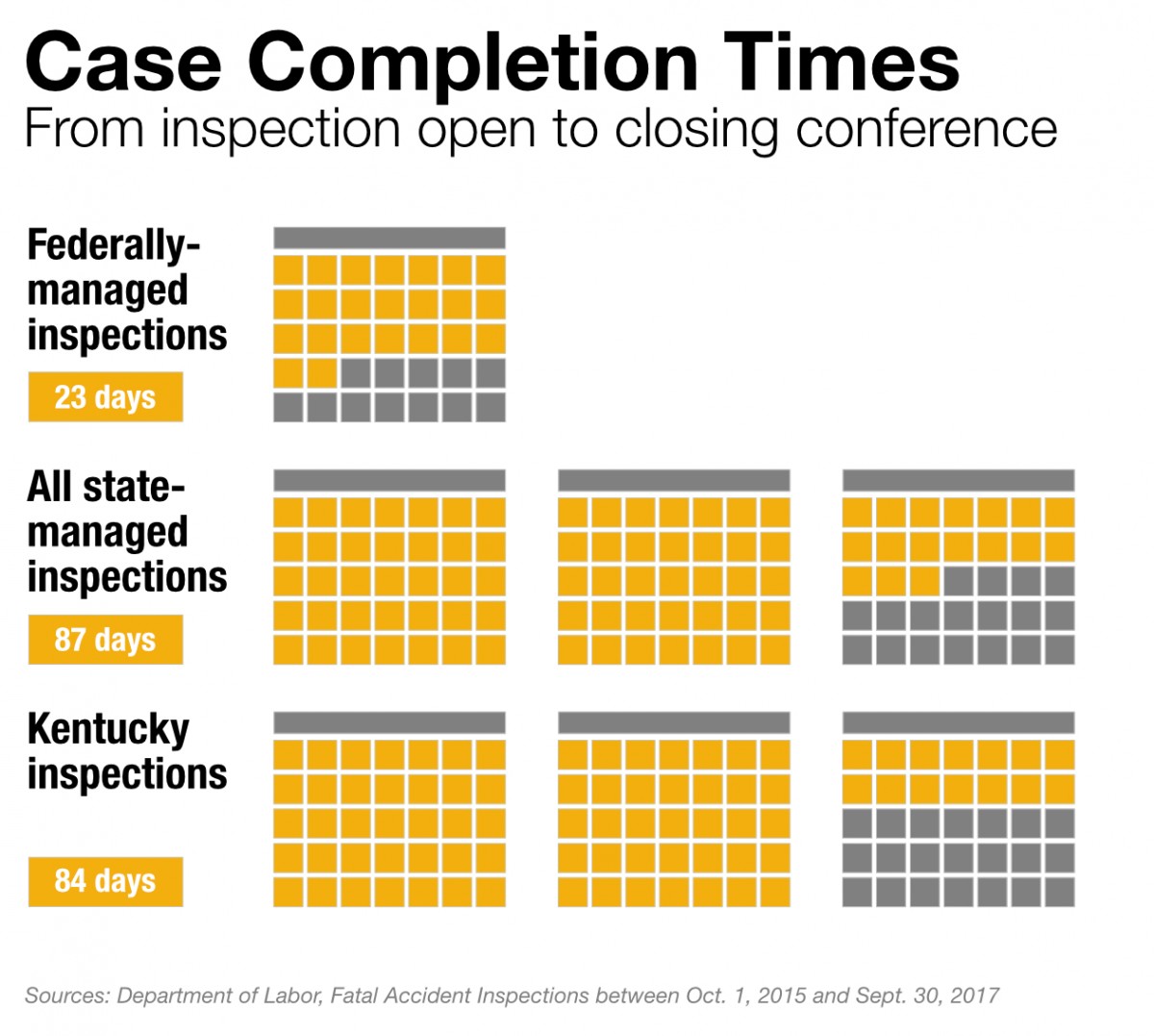

Arizona’s industrial commission has been under fire from the news media and the federal government. In December 2016, the Arizona Daily Star reported that the commission, which reviews proposed ADOSH penalties exceeding $2,500, routinely reduced them even though, a federal OSHA official told the newspaper, it often failed to provide clear justification for its cuts. In a May 2017 letter to the commission’s director, the head of federal OSHA’s Phoenix Area Office found that the commission was “reducing penalties in a seemingly arbitrary manner without regard for the factors in the [ADOSH field operations manual]. This practice reduces the deterrent effect of higher penalties and fails to ensure that employers within the state are treated equally.”

The commission responded in August 2017 that it was “legally authorized to adjust penalties [proposed by ADOSH] upward or downward” and that it “strongly disagree[d]” with federal OSHA’s claim that it had been “operating outside of its legal authority.” In an emailed statement to the Center for Public Integrity, which inquired about the Rope case, commission spokesman Trevor Laky wrote, “Every workplace fatality is a tragedy and the Industrial Commission of Arizona works every day to prevent workplace injuries and educate employers and employees on workplace safety.” The commission, he wrote, has the latitude “to revise penalties based on specific circumstances.” A U.S. Labor Department spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

State Troubles, Federal Intervention

The ability of states and territories to create and maintain their own safety programs is rooted in Section 18 of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. But the track records of those programs vary widely. Some are cash-starved and suffer from high staff turnover and investigative lapses as a result. Others are relatively well-funded and stable. Recently released federal audits of the 28 programs (six of which cover only public-sector employees) found significant problems in Arizona, Illinois, Kentucky and Maryland, for example, while praising Iowa, New Jersey, Oregon, Tennessee and Washington.

Sometimes the federal government must intervene. A September 1991 fire at a chicken-processing plant in Hamlet, North Carolina, killed 25 workers and injured 55. The Imperial Foods plant, then 11 years old, had never been inspected by state workplace-safety officials; investigators found that the dead and injured were trapped behind locked fire doors.

The North Carolina Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Division fined Imperial Foods $808,150 for 83 violations; owner Emmett Roe was sentenced to nearly 20 years in prison after pleading guilty to 25 counts of involuntary manslaughter and served just under four years. The month after the fire, federal OSHA showed its lack of confidence in North Carolina regulators by asserting “concurrent enforcement jurisdiction” with the state. That lasted until 1995, by which time the Occupational Safety and Health Division had beefed up its enforcement staff and made other improvements.

A decade ago, construction workers on the Las Vegas Strip were dying at such an alarming clip that federal OSHA conducted a special review of the Nevada program. The review found, among other things, that state investigators weren’t properly trained to spot construction hazards. The feds forced the state to develop a corrective action plan and kept close tabs on it. The most recent federal audit of Nevada was largely positive, though deficiencies were noted.

In 2012, federal OSHA began policing certain industries in Hawaii — and considered taking over the entire state program, which was “failing,” according to Jordan Barab, then a deputy assistant secretary with the U.S. Labor Department. Federal intercession ended in 2017.

Ron Hayes has seen the gamut in state workplace-safety enforcement. Hayes became an advocate for families of accident victims after his 19-year-old son, Pat, suffocated in a Florida grain bin in 1993. He cajoles and coerces public officials in his South Alabama drawl. He writes a lot of letters. He’s given presentations to managers and inspectors with a dozen state programs, coaching them on how to communicate with victims’ relatives. He heavily influenced a 2012 U.S. Labor Department directive instructing federal OSHA employees to consult families during fatality investigations.

Hayes, 69, quit his job as an X-ray technician in Fairhope, Alabama, in 1996 to form a nonprofit called the FIGHT (Families in Grief Hold Together) Project. He calls himself a “big fan” of state programs — provided they’re well run. “I believe in them,” he said. “They’re more responsive [than federal OSHA].” He has no patience, however, for faltering programs like Kentucky’s. The state was flagged by federal OSHA this summer for routinely mishandling worker-death investigations. In a written statement, a U.S. Labor Department spokesman said federal officials are “working with the Kentucky Labor Cabinet to craft a corrective action plan.” In a separate statement the spokesman wrote, “OSHA monitors all 28 State Plans closely throughout the year.”

Hayes, who is advising the families of several fallen Kentucky workers, is skeptical. “Kentucky businesses are really blessed,” he said. “Companies walk away with no citations, no training [requirements], no nothing. They walk away scot-free, and a dead man can’t speak.” Kentucky officials declined interview requests but said in their response to the most recent federal audit that the state “makes every reasonable effort to determine the cause” of fatal accidents.

Kevin Beauregard heads North Carolina’s safety agency and chairs the Occupational Safety and Health State Plan Association, which includes all 28 state and territorial programs and meets three times a year. While the group tries to “make sure we have some consistency” across programs, Beauregard said, consistency is hard to attain when federal funding is so paltry and state funding so erratic. North Carolina gives its program enough money to function smoothly, he said.

But others don’t and experience a steady churn rate among their compliance staffs. This has tangible consequences. For example, the most recent federal audit of the Illinois program, which covers only state and local government employees, found that the Illinois Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Division met a skimpy 38 percent of its inspection goal during the 2017 fiscal year. “The leading factor,” the audit found, was “staff turnover and difficulty filling vacancies.”

Under the law, the federal government can pay for up to 50 percent of each state’s or territory’s program. It hit this mark in the 1970s, Beauregard said, but fell increasingly short as the programs grew. Today, he said, things are “completely out of whack.” Because the federal government hasn’t held up its end of the bargain, state and territorial safety agencies spent a collective $112 million beyond what they were required to during fiscal 2017, a study by the State Plan Association found. That’s up from $40 million in extra outlays in 2005.

Congress could fix the problem but has been “reluctant to increase the state plans’ budgets over the years,” said Barab, the former U.S. Labor Department official. Last year, according to the State Plan Association, only 18.2 percent of the federal OSHA budget went to the 28 programs.

By one measure, the state and territorial agencies are more productive than their federal counterpart. According to data compiled by the AFL-CIO, they did a collective 43,593 workplace inspections in 2017 — an average of 1,557 per jurisdiction — compared to 32,396 in the 24 states policed by federal OSHA, an average of 1,350. But the agencies lagged by another measure. Their average fine per violation was $1,289, the AFL-CIO found, compared to $3,839 for federal OSHA.

“You get the good, the bad and the ugly with state plans,” said Marcy Goldstein-Gelb, co-executive director of the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health, an advocacy group. “You have the opportunity to add protections you may or may not get at the federal level. The flip side is that state plans are much more subject to politics, in implementation and budget.”

“The inherent problem with state plans is that [federal] OSHA really doesn’t have the capacity to oversee them,” Barab said. “The basic tool OSHA has is essentially the death penalty — taking away the state plan. That’s a burdensome hurdle. Nobody really wants to do that.”

‘It’s best you don’t see’

Lariat Irving Rope, who was born June 10, 1962, on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in southeastern Arizona, had three sisters and three brothers. He joined the U.S. Army in 1981, was discharged in 1989, and went to work at Sapa Extrusions three years later. He was known by his family and friends as “Low Rider,” “Pops,” “Cherry Bomb” and “Fatts,” according to his obituary, and, while gregarious, “wasn’t the type to sugar coat things.” He had a fondness for travel, photography, family gatherings, the reggae band Stick Figure and the University of Arizona Wildcats. His unusual first name came from his father, a lifelong cowboy.

Photo: Courtesy of Evelyn Hinton

On the day of his death last year, Rope was finishing a 12-hour, overnight shift as a caster, helping guide molten aluminum logs into a pit of water 10 feet wide, 11 feet long and 22 feet deep. A fall-protection table, with slots for the logs, was designed to be maneuvered over the pit to keep workers from falling in, but the pit typically would be uncovered for five to 10 minutes during the casting process, the Industrial Commission of Arizona said in its April report. “It was during this time when employees would be exposed to an open pit fall hazard,” the commission found.

At about 5:45 a.m. on November 8, Rope “was observed trying to move an aluminum log into position with his hand and as he stepped forward, he stepped along the edge of the pit, losing his balance” and falling in, the report says. His 32-year-old son, Andre, was working in another part of the plant when it happened and bolted for the scene but was deterred by a co-worker, said his aunt, Evelyn Hinton. “Someone stopped him and said, ‘It’s best you don’t see.’”

Lariat’s wife, Debra, learned of the accident around 6 a.m. and began calling her husband’s extended family. Hinton got the word around 6:30 as she was preparing for work. “We turned on the TV,” she said. “They were still describing it as a rescue.”

Hinton called her brother Dave, the only sibling other than Lariat who lived in Phoenix, and he took off for the Sapa plant, in an industrial district west of downtown. Around 7:30, some 30 members of the Rope family — including Lariat’s parents, Rosie and Evan Rope Sr.; Hinton; another sister, Rose; and a brother, Evan Jr. — left the reservation for the 116-mile drive to Phoenix. Lariat’s brother Johnny and sister Carrie set out from Morenci, Arizona, and Dallas, respectively, by car and air.

The group from San Carlos got to Sapa around 9:30. Evan Sr., a pastor, “thought Lariat would be OK, but he’d already passed,” Hinton said. “He was just traumatized to find out.” Family members were ushered by security into the nearly-empty factory — the workers had been sent home — and waited to view Lariat’s body. What they saw looked like something from a horror film. “He was wrapped up in some kind of red-colored plastic,” Hinton said. “I don’t know if that was his blood.”

The precise cause of Lariat’s fall remains in doubt. Hinton said Andre told her a crane near the pit reportedly had been acting up “all night.” Dave Rope said several of his brother’s co-workers told him they’d heard a loud noise before Lariat fell. (Industrial commission spokesman Laky wrote that “ADOSH did a thorough investigation regarding the crane incident and any ‘loud noises’ reported would have been investigated.”)

In response to an inquiry from the Center, Hydro Extrusions North America, which acquired Sapa last year, issued a written statement. “At Hydro, safety is our first priority,” the company said. “We immediately reported this incident to the relevant authorities and worked closely with them, along with our internal experts, to complete a thorough investigation. We shared the information we learned with other locations within Hydro, as well as our industry, in order to help prevent future incidents and minimize risk. Our thoughts continue to go out to the family and colleagues of the employee involved in this tragic event.”

Hinton is unmoved. She said she can’t understand why the company didn’t fix the fall-protection table before Lariat’s death. She called the state-imposed penalty of $5,250 “way low.” Peter Dooley, a senior project coordinator with the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health who helped Hinton’s sister-in-law, Ingrid Rope, obtain investigative documents from the state, said the industrial commission’s reduction of the fine from $7,000 “sends the wrong message to employers that put their workers at risk.”

The accident shook the entire Rope family, none more than Andre, the older of Lariat’s sons and a recovering alcoholic. “My brother had been nursing him back to health,” Hinton said. After his father’s death, Andre returned to work at Sapa for a brief time but started drinking again and was let go. “He just stopped caring about everything,” Hinton said. He died on Easter Sunday of this year.

Jim Morris is managing editor for environment and workers’ rights at the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization in Washington, D.C.

This story is part of a series of reports called Fatal Flaws, originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource, the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting and the Center for Public Integrity.