When Jennie and Brian Kahly decided to move to a 150-acre family farm in West Virginia’s Preston County, they thought a lot about what type of farmers they wanted to be.

“We went ahead and made a list of values, and one of those values was to minimize our fossil fuel use,” Jennie said. “That doesn’t mean we don’t use fossil fuels. It means we make a conscious effort to minimize them.”

Installing solar panels was high on their wish list. After two years of planning, this fall Possum Tail Farm began running on sunshine.

The Kahlys installed an 18-kilowatt solar array. Fifty-two panels sit atop the steel roof that adorns the farm’s storefront. Inside, they sell cuts of the certified naturally-grown beef. Two inverters convert the energy created by the panels into electricity that can be used on the farm and sent into the grid. Anything extra they produce gets credited to their power bill.

In recent years, the cost of solar systems has dropped significantly, but it can still be a costly investment. The Kahly’s got three quotes for their system, ranging from about $20,000 to almost $50,000.

“We had to work out how to make it work financially and logistically,” Jennie said.

As small farmers, the Kahlys qualified for two federal programs through the U.S. Department of Agriculture: a low-interest loan from the USDA’s Farm Service Agency,and a federal grant through the agency’s Rural Energy for America Program that covered 25 percent of the cost of the panels.

Without this federal assistance, they said, installing this solar system would have been out of reach. And in West Virginia, a complete lack of solar-friendly policies or incentives further complicated the financial picture.

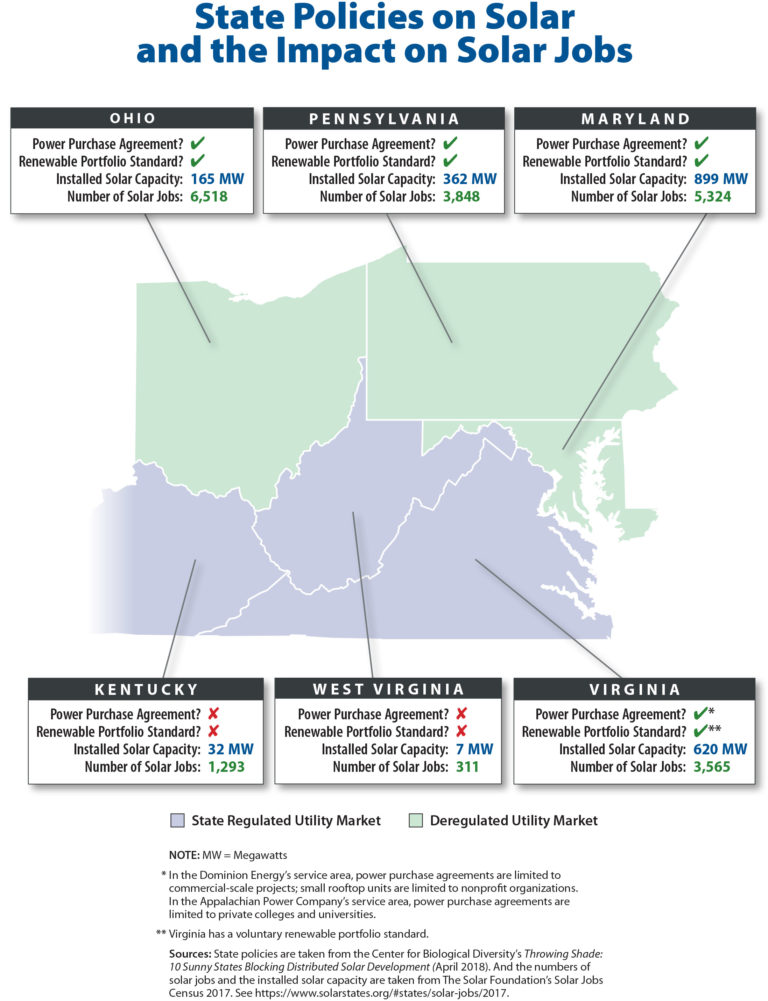

Across the Ohio Valley, state adoption of solar policies looks like a patchwork quilt. Experts say weak policies make it harder for residents and businesses to afford to install a solar system and make it less likely that the region will attract jobs and economic benefits associated with this fast-growing industry.

Dim View

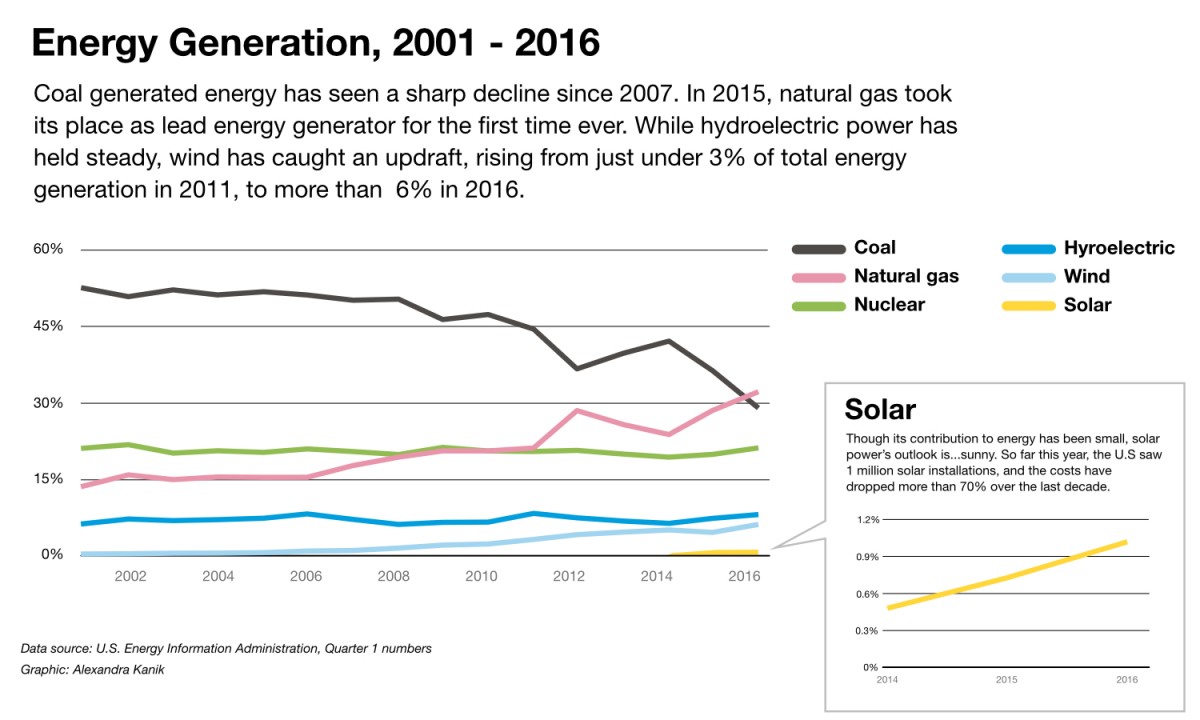

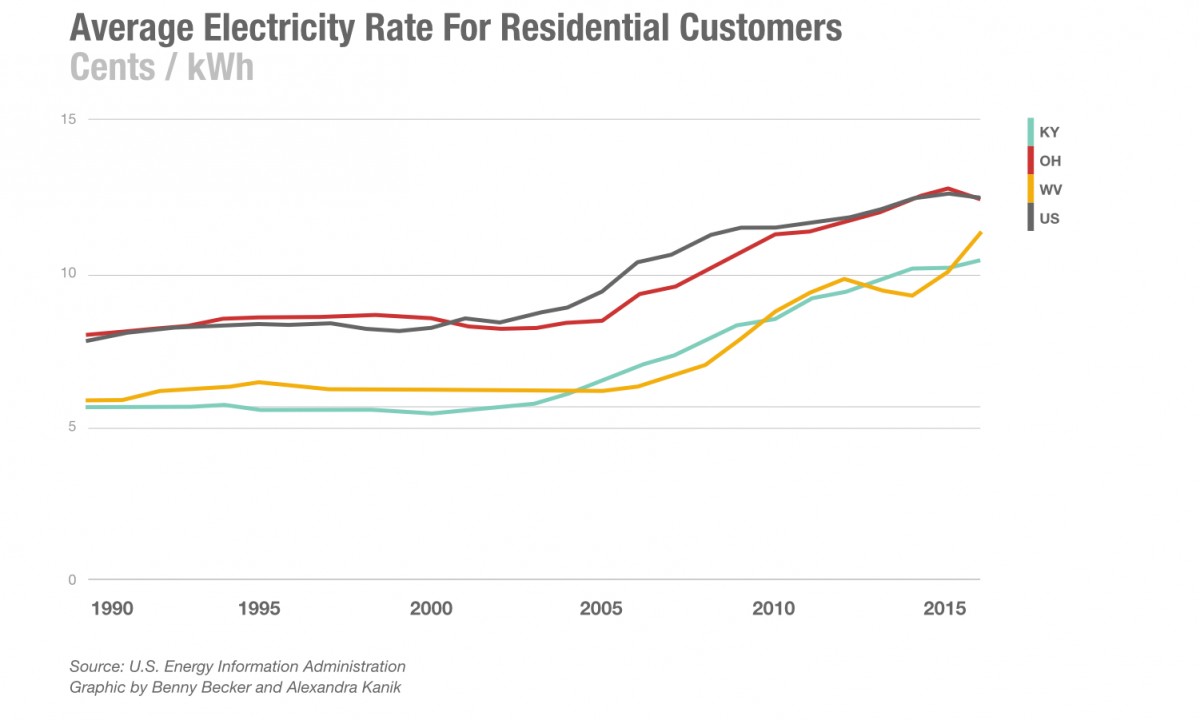

With less solar energy on the grid, consumers in these coal-heavy states have fewer options to counter rising power costs.

“If customers are able to get their own solar, that’s a hedge against rising electricity costs,” said Jamie Van Nostrand, director of West Virginia University’s Center for Energy and Sustainable Development. “You’re going to be able to generate your own electricity and pay your utility less because you’re basically buying fewer electrons.”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, in 2017, coal-fired power accounted for 93 percent of West Virginia’s electricity, 79 percent of generation in Kentucky and 58 percent in Ohio.

As coal-fired power plants continue to shutter, rate-payers in Kentucky and West Virginia are footing the bill for decommissioning costs. Coal-heavy American Electric Power customers in West Virginia and Kentucky, in particular, have seen their power prices skyrocket. The utility’s customer base is also shrinking, which is further compounding the problem.

This week, the West Virginia Public Service Commission agreed to review a proposed 4 percent rate increase requested by Appalachian Power. The utility had asked for an almost 12 percent rate hike. This is on top of a 29 percent increase between 2014 and 2018.

Similarly, Kentucky Power customers have electricity bills that rank among the highest in the nation for an investor-owned utility, according to 2016 numbers from the EIA.

“There’s no question our electricity bills have gone up pretty dramatically the last three or four years because we’ve doubled down on coal in this state and the utilities have been able to purchase coal plants that were formerly owned by their merchant subsidiaries and put them in their regulated rate base,” Van Nostrand said.

He added that boosting the ability of individuals, businesses and municipalities to invest in solar could help control energy costs.

“It’s basically helping people to manage their electricity costs because our electricity costs are going up and they’re going to continue to go up,” he said.

Power Policies

There are two main policies that states can adopt that incentivize solar installation. Most states have one or both, but according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory West Virginia and Kentucky have neither.

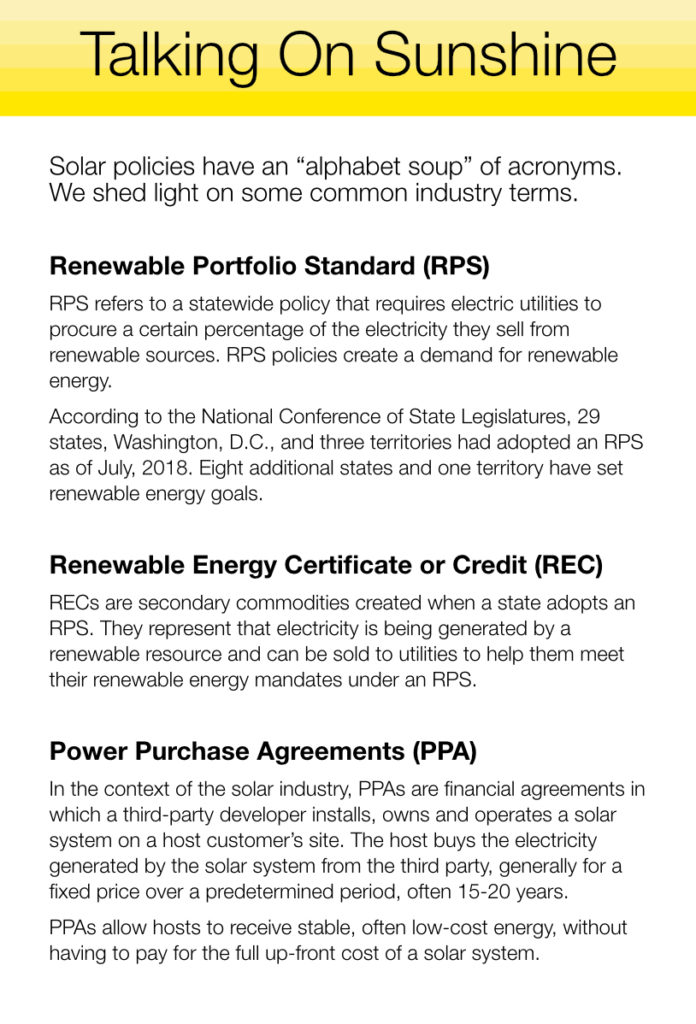

The first is called a third-party power purchase agreement, or PPA. That allows a private, third-party developer to install a solar system on your property and then sell you the power that that array produces at a fixed rate for typically 15 to 20 years.

Tax-exempt entities such as schools, churches and local governments especially benefit from PPAs, because they aren’t eligible for the 30 percent federal income tax credit. Beginning in 2020, the federal solar tax credit will begin ramping down.

“A power purchase agreement allows them to install solar with zero up-front cost, potentially lower their energy bills from day one, and it’s also a really popular way for commercial businesses to go solar on a larger scale than that business is potentially going to be able to invest in with their own capital up front,” said Autumn Long, program director of the nonprofit West Virginia Solar United Neighbors.

In West Virginia, power purchase agreements are illegal under current law. That’s something Long’s group hopes might change during this upcoming legislative session because they see it as a major barrier to bringing new business to the state.

“West Virginia has a lot of land that could be made available for this type of larger scale solar development if third-party developers were allowed to sell that power to willing buyers,” she said. “They’re out there and they represent major economic investments that we’re currently not taking advantage of.”

The second policy that can help boost solar is a Renewable Portfolio Standard, or RPS. These require electric utilities to procure a certain percentage of electricity from renewable sources, which creates a demand for renewable energy like solar. Individuals and businesses with solar panels can help utilities meet those goals and make some extra cash by selling renewable energy credits or certificates, also called RECs.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 29 states, Washington, D.C., and three territories had adopted an RPS as of July, 2018. Eight additional states and one territory have set renewable energy goals.

Kentucky does not have one. West Virginia repealed its RPS in 2015 on a bipartisan vote. Opponents of the policy argued it was no longer economically in the state’s best interest.

Van Nostrand and others argue that the loss of the RPS means those who do install solar in these states are losing out.

“So you’re building solar panels in West Virginia, installing them in West Virginia, you’ve got the payments for the electricity itself, the electrons, but you’re not getting anything for the fact that those electrons are produced by renewable resource unlike Maryland, unlike Ohio, unlike Pennsylvania, unlike Virginia,” he said.

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs

Advocates for solar say the biggest thing at stake is jobs. In 2017, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected that solar installer will be the single fastest growing job in the country over the next decade.

Already, employment data show states like Kentucky and West Virginia that don’t have pro-solar policies on their books are lagging behind their neighbors. According to the 2017 Solar Foundation solar jobs census, solar employs more than 6,500 people in Ohio. Kentucky has just under 1,300 solar installer, and in West Virginia it’s just over 300.

“I think with the right state and policy support, we can see a lot more of this development and attract a lot of jobs as a result,” said Dan Sawmiller, Ohio energy policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

He and others have been working with utility American Electric Power in Ohio to leverage a massive proposed solar project to bring not only solar installers, but hopefully, solar supply chain manufacturers.

As part of a legal settlement, AEP is shutting down much of its coal-fired power plants and is asking regulators for permission to install at least 500 MW of wind and 400 MW of solar energy projects. Ohio has an RPS, but utilities in the state have largely met their renewable energy requirements by purchasing credits or RECs produced out of state.

“We set a goal of a minimum of 400 MW in the idea that a solar project at that scale is large enough to attract supply-chain manufacturing partners,” Sawmiller said.

That includes solar panel makers, but also companies that produce power inverters and more.

Once they’re here, it becomes more competitive to develop additional solar projects in Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky.”

Having a robust renewable energy policy on a state level can also affect job growth in another way. Increasingly, companies around the world are making commitments to source some, if not all, of their electricity from renewable sources, said Long, with Solar United Neighbors.

“And it’s not just Amazon, it’s GE and GM and Procter & Gamble which is already here,” she said. “Companies from automakers to textiles to food and beverage to tech companies to banks, all of them have signed on to 100 percent renewable energy and they all demand access to solar to meet those internal goals.”

Growing Greener

Back at the farm, the Kahlys are quick to note that installing their solar system was still a good investment despite the lack of state-level incentives.

Brian, whose background is in computer programming, created a spreadsheet that breaks down the cost-benefit ratio. It shows that if energy prices remain steady, the system will pay for itself in about 15 years.

“If the price of energy goes up faster than that we make out sooner,” he said. “The life of the system is 25-30 years, so there’s a lot of time there yet in the future that then becomes all free energy.”

That sentiment is one Dave Fleeharty, with MTV Solar, hears a lot. The Berkeley-Springs, West Virginia, company installed the solar array at Possum Tail Farm. He said despite a lack of state-level incentives in West Virginia, they still do about half their business here.

“We’d love to see more state incentives, but the fact of the matter is we’re probably at the historical low for the cost of solar right now,” he said. “So even without any incentives we’re finding churches doing it that don’t have the tax breaks at all. It’s still a financially viable and smart investment with a very good return.”

By Brian’s count, the rate of return for the farm’s investment is expected to be somewhere between 7 and 8 percent at the end of 30 years.

“You’ve got to be a really good investor to have that kind of rate of return in the stock market right now I believe,” he added.

This story was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.