In 1969, the world’s attention turned upward to the Moon, as Neil Armstrong took humankind’s first momentous step off Earth onto another world.

But that year also saw momentous federal legislation spurred by a disaster that riveted the nation’s attention downward, hundreds of feet below the Earth and the hills of West Virginia.

The simply named Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act was enacted into law the day before New Year’s Eve in 1969. It ratcheted up federal mine inspections, toughened mine standards nationwide and gave miners safety and health benefits they’d never had before.

But the impetus was far from simple.

The year before, on Nov. 20, 1968, 78 miners died in the Farmington Mine disaster, when a series of explosions ripped through the Consolidation Coal Company’s No. 9 mine, north of Farmington and Mannington in Marion County.

While it may seem like ancient history, as the 50th anniversary of the No. 9 disaster is marked this month, its devastation and impact have never quite ended.

Ongoing legal action claims that evidence years after the explosions shows clear culpability on the part of the coal operator in a horrific disaster which continues to haunt families and the community.

‘They’re gonna blow the mine up.’

Joe Megna attended a yearly memorial Sunday in Farmington, situated around a tall black memorial built to remember the lost miners. The coal company erected the memorial atop the old mine as part of an agreement with the dead miners’ widows, who have lobbied, testified, sued and battled for years for redress from their families’ losses on that day.

Among the dead was Megna’s father, Emilio, a section boss. Emilio came to America with his family at age 3 from Italy. Like more than a few European immigrants, he ended up clawing coal out of seams deep below the surface of West Virginia, starting at 14 years old.

Megna said in the days before the mine blew, his father told him, his mother and his close friend Danny how alarmed he was by how the company operated No. 9.

“He told me and Danny and my mom, too, that they’re gonna blow the mine up. He said they’re not taking care of it,” Megna said.

There were high levels of the explosive gas methane, his father said, and the company was not routinely rock dusting — applying pulverized limestone to mix with coal dust to prevent explosions.

“He said, ‘I’ve never been scared in my life of the mines. But I’m really concerned,’” Megna recounted.

No death is more tragic than another from that day, but as Emilio descended into the mine that November night, it was surely with great anticipation.

It was to be the 48-year-old immigrant’s final eight-hour shift below ground. Emilio and his family, with help from Danny, were preparing for the grand opening of their new gas station in Worthington that Saturday and a job in the sunshine and fresh air.

At midnight, Emilio and 98 other men headed underground on a cold Autumn night for the midnight “cat-eye” shift. At about 5:30 a.m., a series of explosions tore through the underground mine complex.

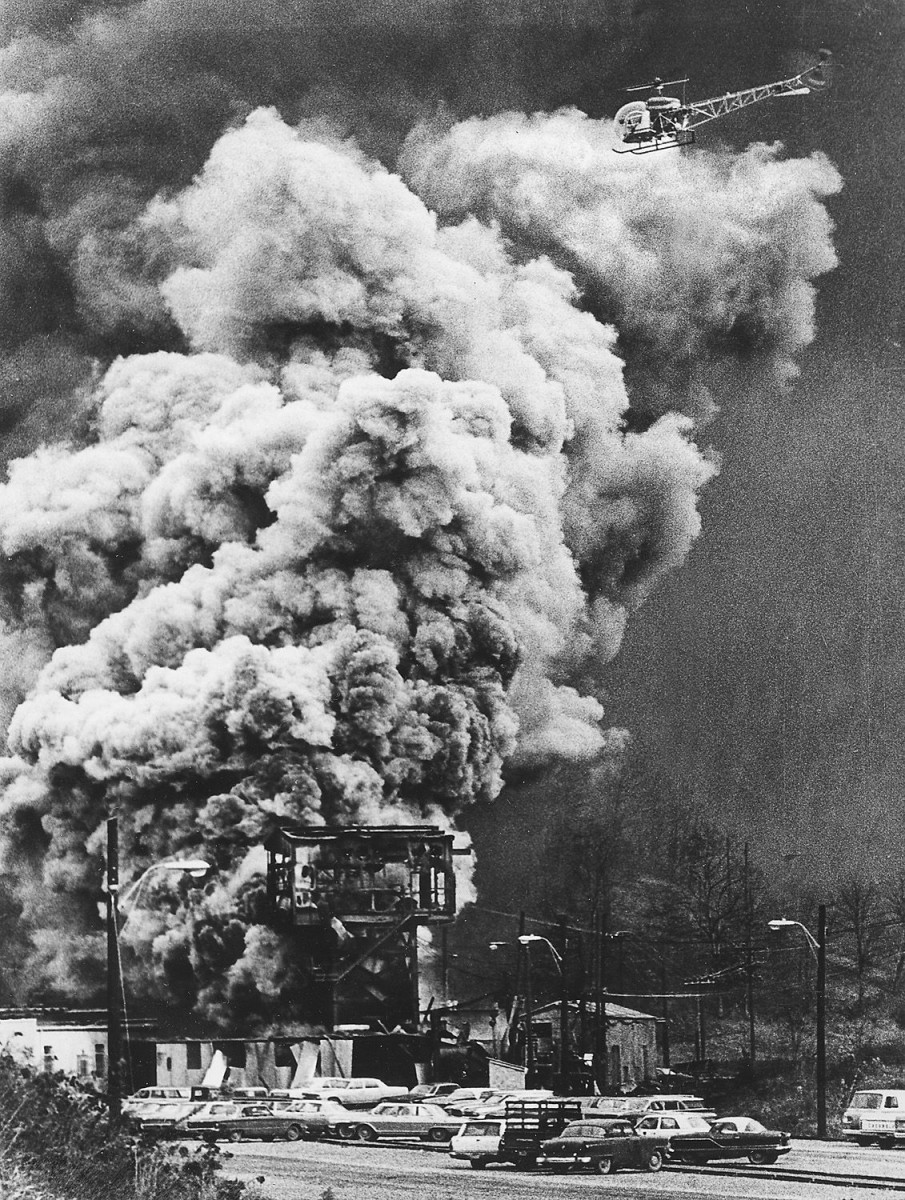

The explosions blasted a plume of smoke more than 150 feet high from No. 9’s mouth, captured in an iconic photo by then-Charleston Gazette photographer Lawrence Pierce. The explosions were so powerful a motel clerk reportedly felt them 12 miles away in Fairmont.

A total of 21 miners got out, with several rescued via a crane dropping a hoist bucket into a shaft. But 78 remained trapped.

Media poured into the area as the fires burned for a week. CBS anchor Walter Cronkite and others reported nightly to the nation on the unfolding events while miners’ families crowded into the nearby company store for updates.

Yet nine days later, with the fires still burning, rescuers pulled back. Air samples from drill holes showed no breathable air below ground. In what must have been a terrifying sight to families, the mine was sealed with concrete on Nov. 30, 1968, to deprive the fire of oxygen.

Emilio Megna never made it to his grand opening. Yet more tragically, his body and those of 18 other miners remain entombed deep within No. 9 to this day.

It was not until September 1969 that the mine was unsealed to attempt to recover the dead, mining coal in the process. Cave-ins hampered the effort and the recovery dragged on for a decade. By April 1978, 59 families at least had the small comfort of burying their father, son, uncle, grandfather or friend.

But not Joe Megna and his family. The company finally abandoned efforts to retrieve the body of his father and the 18 other miners, thought to be below, or near, the site where the memorial stands today.

The ripples of that day fanned out in odd and disturbing ways, such as when Joe tried later to find work in the mines. He eventually did land a miner’s job, but Emilio’s death was seen as a red flag to coal operators.

“My dad was killed and they thought I’d be a radical troublemaker,” he said. “I just wanted a job to take care of my family.”

‘Never a closed case.’

Bonnie Stewart, an investigative reporter and former West Virginia University journalism professor, spent three years researching her book, “No. 9: The 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster,” released in 2011.

Stewart, who now teaches in California, attended Sunday’s memorial out of respect for the families and to share an ongoing grief that has yet to be resolved.

“For these families, it was never a closed case,” Stewart said. “It still isn’t.”

Her book details in excruciating, often harrowing detail how and where each of the recovered miner’s bodies or remains were found and identified.

There is Albert Deberry, for instance. He was killed by poisonous gas and identified by his miner’s ID, wristwatch and wedding ring.

And roof bolter John F. Gouzd, 21, whose nephew, Joe Manchin, would later become governor of West Virginia and is a current U.S. Senator.

Gouzd was not the youngest man who died in the mine, though. Trackmen Randall Parsons was 19 years old. He had worked underground for just eight days.

Stewart’s book details the drama and heartbreak aboveground. How, for instance, Joe Megna dashed through snowy woods after grabbing some of his clothes from a sleepover at Danny’s house after word came that the mine had blown up.

Stewart’s book lays out in detail a pattern of dangerous conditions in No. 9, revealing a mine operation with a long and notorious history for lax standards and a credo of breakneck production over safety.

The book delves into records and testimony that show Consolidation Coal’s operation of the mine featured routine poor ventilation, high levels of coal dust and methane gas, and a failure to adequately test for methane.

The book traces evidence that an alarm on a key ventilation fan used to pull methane gas from the mine had been disabled before the explosion. The alarm would have shut off power to No. 9 and triggered an evacuation of all 99 miners that day.

That action, and the mine’s routinely poor conditions, yielded a catastrophe, Stewart said. “I think all of those things played out in No. 9. Then, you actually had someone dismantle a safety alarm.”

“That was totally preventable, and totally premeditated that somebody made the decision to do that. It was in my mind a criminal act,” Stewart said. “They’d wired around it so it wouldn’t go off.”

No one has ever been held legally to account for the No. 9 mine disaster, said Stewart.

“The federal government did not write a formal report until 20 years later. The West Virginia Department of Mine [Health and Safety] didn’t write any final report. It’s like they didn’t want to have to deal with it.”

‘Fraudulent concealment’

West Virginia attorney Timothy Bailey represents the miners’ families in an ongoing legal case that seeks to bring some closure and more compensation to all the families, some of whom previously received $10,000 settlements from the coal company (about $60,000 in today’s dollars).

Earlier this year, the families asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit to reinstate a wrongful death lawsuit filed in 2014.

In 2017, a federal judge threw out the case, saying the suit “brought 46 years after the explosion, is late by more than 44 years,” based on the fact wrongful death cases in West Virginia need to be filed within two years.

But Bailey has argued that it wasn’t until 2014 that the families learned the mine’s chief electrician had disabled the fan and a then, a few years later, his identity. Except for the company’s “fraudulent concealment” of the causes of the explosion and its hiding the electrician’s identity, the families could have filed the wrongful death case in time, he says.

The two-year limitation should be extended based on when the family learned of those concealed facts, said Bailey in a phone interview.

The Fourth Circuit sent the case back to the West Virginia Supreme Court to answer some questions on the application of West Virginia law, Bailey said. “We’re beginning the process of briefing those issues.”

“Once those questions are answered, you’ll pretty much know whether the appeal is going to be successful or not based on the answers to those questions,” he said.

Should the families prevail, a huge settlement would result, said Bailey, with damages accruing along with interest since the 1968 disaster. “It’s a very, very substantial figure.”

But who will be held responsible?

‘A red herring’

In 2013, the mining company — which through sale and mergers had become Consol Energy — sold some of its mines to Murray Energy, which took on legal liabilities from the old Consolidation operations, including the No. 9 mine.

Murray Energy has declined to comment on the claims made in the families’ attempt to revive the 2014 lawsuit, except to release a statement that said:

“Murray Energy did not even exist in 1968, when the accident occurred. There is no higher priority at Murray Energy than the health and safety of our coal miners.”

Bailey dismissed the statement as “a red herring.”

“When you take it all, you take it all,” he said. “That means you take the good with the bad.”

Murray Energy wants to assert “we didn’t do it,” said Bailey. “We’re not suing you because you did it. We’re suing you as the successors to the folks who did it.”

It is a half-century later, and the reverberations of the explosions at No. 9 continue to echo, Bailey said.

“Think of the ripple effect on brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, high school classmates, members of churches,” he said. “If you were to put a circle around the area that was impacted by this many deaths — it’s shocking how many people were impacted.

It’s “a horrible tragedy” when a community loses just one coal miner, said Bailey. “Here we have a community that lost dozens of coal miners.”

“And so, they’re hurting. The thing most human beings want is answers. You want closure.”

‘Never quite the same’

Stewart hopes her book and the ongoing efforts to aid the families offers some small consolation.

“I just hope a more thorough telling of what happened is helpful to them in some way,” she said.

The Coal Mine Health and Safety Act, with its nationwide spotlight on mining safety and the health of miners, is also a legacy of the loses from that day, she said.

“To me, it’s a community that will never be quite the same. But I do hope they find comfort in the fact the federal laws are stronger and that they actually know what happened. Even if they’ve been yet to date to really hold the company responsible,” Stewart said.

“It’s a positive legacy for those who died. As sad as it is — and as so often happens— that you have to have something horrible happen before people are moved to make positive change.”

Joe Megna is still waiting on justice for his father’s death and for so many other No. 9 miners.

The case deserves airing, even fifty years later, given how the company hid key facts from the families, he said. “How do you know about something when they hide it? They did production over safety.”

Megna conjured the image of Lady Justice.

“You see that lady with the scales and the blindfold? They say justice is blind? That means that it should be blind whether you have money or not. In this case, it’s blind because money talks.”

He and the other families who still bear deep losses from the No. 9 disaster are not pressing the case for cash, Megna said.

“It’s not about the money. It’s about the truth. Let the people know what really happened. It wasn’t an accident.”

Douglas Imbrogno is a freelance writer and video feature producer based in West Virginia. Contact him though his site thestoryisthething.com and thewebtheater.com