This story is part of a series of special reports titled “Work in Progress,” with support from Foothills Forum and Rappahannock News looking at the dynamics of changing agricultural economies. The story was originally published by Rappahannock News.

Rappahannock is facing an economic transition. But it has a long history of dealing with changes brought by forces beyond the county line.

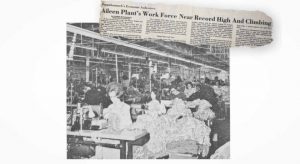

Janet and Roy Alther still remember the summer day in 1994 when the management at the Aileen Inc. dress factory, the largest employer in Rappahannock County at the time, summoned its staff to the cafeteria to tell them they were closing shop.

For the Althers, who had worked at the Flint Hill plant for 27 years, it was time to rethink, regroup and, to some extent, reinvent.

Similar upheavals have marked the lives of many Rappahannock residents over the years, as farms, firms, retail outlets, car dealerships and apple processors shut their doors or downsized. For the Althers, the next steps included commutes over the mountains to neighboring counties, jobs in hospitals and in a long-john factory, along with growing apples and peaches at their home and turning down beds at the Inn at Little Washington while the guests ate dinner.

Like so many of their neighbors in the county, the Althers have learned to count on two fundamentals: first, in economic life, change is the only constant; and second, the capacity within people to adapt and restructure seems inexhaustible. Today, the Althers work to lure traffic off Route 211 up Old Hollow Road and into their Sperryville farm store — Roy’s Orchard & Fruit Market. The shop, perched on a hill above rows of fruit trees, sells apples, peaches, berries and eggs, but also a full range of groceries, emphasizing strawberries in May and fresh turkeys in November.

Photo: Luke Christopher, Rappahannock News

The story of economic transition, and the shifting landscape of opportunity and loss, has long been part of Rappahannock’s history, no matter how much the community has tried to protect itself against change. A welcome source of job creation in one era may, a few decades later, only live on in nostalgic reunions.

Today, another transition is on the horizon. More and more weekenders are becoming retirees. Family farmers, long the community’s lifeblood, are growing old, too, and global competition and rising operating costs have made it increasingly difficult for them to sustain their businesses. The aging population and the increase in part-time residents and tourists will likely influence the mosaic of work and workers in the county. Technology and shifts in eating and harvesting will be equally important. The shape of any transition is perhaps clearest when people look back on it years later, but efforts to listen and take stock can help a variety of economic actors calibrate what might be the smartest moves today.

Now what?

As in counties and towns across the country, people debate the competing merits of befriending change, or staving it off. But the machinery of economics goes on altering the landscape through shifts in behavior and technology, as well as through additions and subtractions in the ecology of competitors, suppliers, transportation patterns and weather. Time itself, of course, is a relentless shape-shifter, changing consumer tastes, sprouting new technologies, and retiring those who knew or cared about how it all worked in the past.

Families weather the upheavals, not always uncomplainingly, and over time men and women in Rappahannock have shown a robust capacity to step back, to ask: “Now what?” They drive farther to work, or they learn to do things they didn’t know they could, often cobbling together multiple part-time jobs where there used to be a single full-time one. They read the landscape to discern what people want to buy — whether it’s apples or aromatic cocktails — and they find a way to create or complement an income stream by responding to the latest fascination. And when the next upheaval comes, they’re better equipped to adjust, because they successfully navigated the last one.

Rappahannock County, whose 3 percent unemployment rate is far more encouraging than that of many other Virginia communities, could offer a tour of economic adaptation. Dozens of buildings have a then and a now. Juicing plants, grain mills and tanneries have folded, but many of the old structures now house antique stores, catteries, galleries, event stagers and microbreweries. Chutneys are produced where the Aileen dresses once were stitched together. And, most famously, the dreary gas station just off the Lee Highway morphed into the county’s largest private employer — the Inn at Little Washington, where New York Times culinary writer Craig Claiborne said he “had the most fantastic meal of my life.”

Stresses from afar

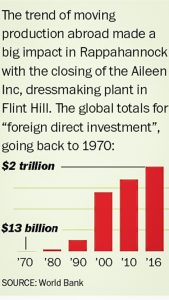

At least some of what went wrong for Aileen had little to do with the New York-based company or with Rappahannock County. By the 1990s, foreign direct investment — where companies buy or establish productive facilities in other countries — was surging, with the total outflows around the world reaching $1.4 trillion in 2000.

In the more global economy, textile and apparel companies in the United States and Europe were acutely vulnerable to competitive pressures from lower-wage countries such as China, Mexico, Bangladesh or the Dominican Republic. Firms like Aileen were shifting production outside the United States or shuttering plants altogether.

Meanwhile, other sources of county employment had been stressed or diminished, adding to the challenges facing refugees from the Aileen factory. The county had revolved around agriculture for two and a half centuries, and as recently as 1970, more than 20 percent of the community’s residents were employed in agriculture. But the decade from 1990 to 2000 saw a precipitous decline in agricultural jobs. According to the U.S. Census, by 2000, a mere 74 individuals worked in farms, forestry and fishing, or 2.1 percent of the working population, down from 11.6 percent or 394 people in 1990.

Two apples a day

Apples once provided seasonal jobs for hundreds of men and women, in orchards, packing sheds, and processing facilities. Reflecting the fruit’s storied past, Virginia producers prided themselves on sending Appalachian pippins to Queen Victoria, who as one historian tells it, “was so entranced that she said there shouldn’t be any tariffs,” opening the way for a buildup of exports to England. Rappahannock orchards diversified their output, producing Red Delicious, Winesap, York and Stamens.

County growers boasted that apples taste better east of the ridge. Autumn visitors to Skyline Drive often pulled off Route 211 to pick up apples to take home. In 1939, the Commonwealth of Virginia Magazine revised the old “apple-a-day” maxim to advocate two apples a day, adding, “Who does not hold his head a bit higher and step a trifle more jauntily and feel a little more zest for living after eating a good apple?” Behind the cheerful sales pitch was a serious threat: Apple growers were losing critical export markets as Europe descended into World War II.

The apple business rebounded, but competition from across the U.S., and eventually overseas, began to erode the profitability in this once robust sector. North Carolina jumped into apple production, undercutting an advantage Rappahannock growers once had as a result of their apples ripening two weeks earlier than those grown in Winchester and further north. Then Washington State found a huge competitive edge in planting controlled irrigation-fed orchards, which weren’t subject to damaging funguses that plague East Coast orchards in periods of heavy rain. Washington State’s controlled-atmosphere storage lengthened the sale’s life of local apples resulting in a massive increase in volumes sold from the state. Finally, juice concentrates from China and South America added further pressures.

Alex Sharp, who stepped into the apple business in 1979, employing about 90 workers at one point, pulled out in 2000, he says, because “your profitability was declining, costs were increasing, and so were your risks,” noting that he worried about running afoul of sometimes complex regulations governing pesticides and migrant labor. He is now in real estate, among other things leasing out spaces in buildings he owns that once housed Aileen and his own apple-packing activities.

To be sure, niche farming and artisanal agriculture are real. Tomatoes in all their varieties are rolling into farmers’ markets, organic farm shareholders are picking up their spring spinach, and local hens are supplying omelet makers at the Inn and area B&Bs. Rappahannock apples are plentiful at roadside stands, local markets and restaurants. Cows graze the hillsides and populate paintings in local galleries. But taken together, these enterprises employ a fraction of the workers who labored on the old farms, orchards and apple-processing facilities.

The same pattern holds true in the non-farm economy. Rappahannock County sprouted 19 start-up enterprises in 2015 alone, but even if all of them succeed, they aren’t likely to lead to large factory-floor operations like Aileen. Moreover, manufacturing — once considered the nation’s most reliable job creator, has shrunk back. Today, manufacturing of any sort in Rappahannock County accounts for just under 6 percent of all jobs. By comparison, in Shenandoah County, manufacturing firms hire about a quarter of the workers.

In 1977, Cheri and Martin Woodard started Faith Mountain Herbs and Antiques, and a few years later converted it into a mail-order business for country crafts. The company succeeded, growing into a $25-million business with a workforce — including seasonal workers — of 150 employees at its peak. But by 2000, internet shopping was beginning to cut

into the mail-order business, and the Woodards decided to sell. “Maybe we could have switched to online commerce,” muses Cheri, now a successful real estate agent, “but it was a different beast.”

Virginia What-ney?

The old Aileen site outside Flint Hill has come to life with the zippy and innovative Virginia Chutney Co., steered by the Turners, an Anglo-American family that savors county life and evangelizes the benefits of chutney with cheeses and meats. In addition to founders Nevill and Clare Turner and their son, Oliver, the business employs seven other workers, most of whom supplement their income by weed-whacking, house-cleaning or landscaping.

The Turners prove that enterprises can succeed with a product the county didn’t know it needed. A now-senior worker at the plant confessed in her job interview that she wondered if chutney was something people wore. The Turners enjoy the exotic, even bewildering, nature of their signature product line with a T-shirt that reads: “The Virginia What-ney Company?” But local recognition is only part of the picture. Virginia Chutney jars line not just the shelves of most Rappahannock retail outlets but show up in grocery and gourmet stores across the country, including giants like Whole Foods and Costco.

The Turners take seriously what customers seem to want, expanding their product line to include pepper jelly and Turkish fig spread, both of which currently outsell the original chutneys. “We rather pride ourselves on being flexible on our feet,” says Nevill, a former businessman. Clare Turner, who handles sales and marketing, adds that the company would be faring less well “if we’d said we’re going to stick to our guns and just do chutney.”

After 12 years of shifting, innovating and retooling, she adds, “Sometimes we feel like we’re flaky because we’re changing all the time.” But change often arrives unasked — as was demonstrated last year when Amazon swallowed up Whole Foods, the company’s biggest distributor. The move ushered in a new set of distribution requirements and some new unknowns. But if individuals like the Turners manage economic upheaval by stepping back and asking “Now what?” it’s apparent that persistent enterprises end up doing the same thing. The survivors have learned to expect change.

You don’t need to go back more than 30 years to see how the economic landscape has changed here. Some of the county’s biggest employers are no more.

An ‘insane decision’

A few miles east of Virginia Chutney, a different family-run company is about to celebrate its 52nd anniversary. Early Carpets provides carpeting and flooring installation, along with cleaning and other services. The Amissville enterprise not only survives but has grown a workforce of 30, along with a fleet of 18 vehicles mainly serving a region of Rappahannock, Fauquier and Culpeper counties, but regularly traveling further afield. As the owners see it, the growth comes by continually asking, “Now what?” then innovating.

Lorraine Early, who founded the company with her late husband John, recalls friends warning that the move to start a business in Rappahannock County seemed “an insane decision because there’s nothing there.” But in the 1960s, locals were warming to wall-to-wall carpets, and the Early’s learned where to buy them and how to install them. Both had grown up in the Piedmont, and initially talked their former school teachers into going wall-to-wall. Hospitals, office buildings and other homes followed.

When hardwood floors came back into vogue in the 1970s, and later ceramic floors, the Early’s picked up the expertise to lay them. Today, the traditional carpets share space with an array of flooring materials, with names such as Appalachian Ridge and Woodland Relics.

When it was clear that the demand for new floors followed the ups and downs of the construction cycle, the company learned about sanding and finishing existing floors. Because some people were sensitive to odors from floors and carpets, they studied up on “velocity odor control.” And noting that Rappahannock was pulling in hundreds of part-time residents and weekenders, the Early’s packaged a cleaning and restoration service for absent homeowners whose pipes had frozen and then burst.

Marketing approaches evolved. When the business revolved around wall-to-wall carpets, the Early’s would send out 42,000 flyers twice a year to generate business. Today, like thousands of other companies, Early isn’t as concentrated on print and paper promotions and gets its message out more often through radio and Facebook.

Continuity comes from the family itself. John Early died in 2014, and daughter Sonja Early Betts serves as manager. Lorraine still handles bookkeeping, mastering QuickBooks software to move away from manual recordkeeping. “They won’t let me grow old,” she says.

Two of Sonja’s children work in the company. Asked about worries or fears, Sonja has a quick answer. “What scares me is somebody who says, ‘It’s not the way it used to be.’”

This article was originally published by Rappahannock News.