The shooting at a Pittsburgh Synagogue last weekend sent shockwaves across the country and the Jewish community is responding.

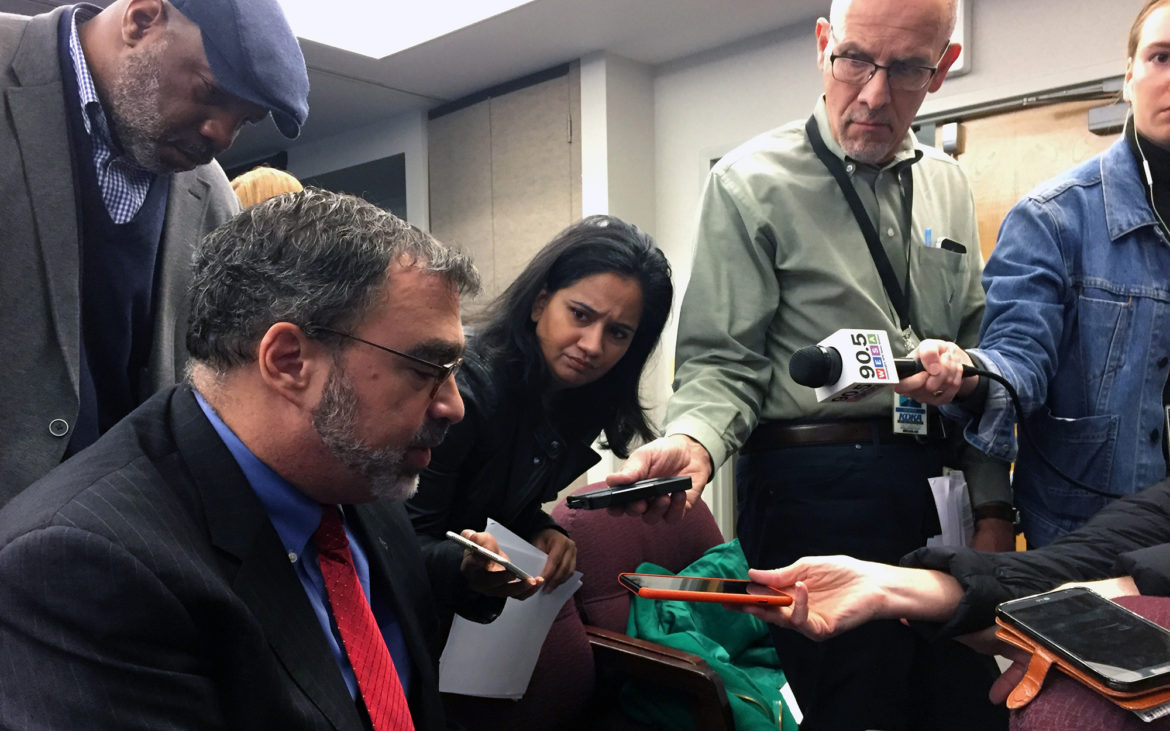

Victor Urecki, the rabbi at B’Nai Jacob Synagogue in Charleston, West Virginia, shared his thoughts on moving ahead in the wake of the tragedy.

Urecki, a member of the Rabbinical Council of America and the Chicago Board of Rabbis, has served as spiritual leader of B’Nai Jacob Synagogue since 1986. He also serves on the Executive Rabbinical Cabinet of the Jewish Federation of North America, the National Council of The American Israel Public Affairs Committee and on the board of directors at the University of Charleston.

Urecki received the “Living the Dream Award” in 2011 for his work on interfaith relations and the West Virginia Civil Rights Award in 2014. He also frequently writes about religious tolerance and mutual respect as a contributing editor to the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

100 Days in Appalachia’s publishing partner West Virginia Public Broadcasting recently spoke with Urecki about moving ahead in the wake of tragedy. Reporter Roxy Todd discussed with him what it means to weaponize goodness. What follows is that interview, edited for clarity and length.

Roxy Todd: For many of us, there’s a sense that we’re living in the midst of a major crisis, that our country is quite divided. To me, the shooting last weekend at the Tree of Life Synagogue makes it feel as though that’s even more true. As a spiritual leader of the Jewish community, but also as a person of faith, what has helped you in the past few days? Is there hope in the midst of so much darkness?

Victor Urecki: What happened at the Tree of Life Synagogue was devastating to America in general and to the Jewish community in particular. In the 240 years or so of our country, the American-Jewish experience has been so different than the way we’ve experienced life as a people for 2,000 years. America was different. Not that there wasn’t some anti-semitism and not that there weren’t anti-semites, but the idea of massacres taking place in places of our worship, those were beyond the paywall–that didn’t happen in America. So, particularly for the Jewish people, this has been a very difficult week. We feel broken, we feel no longer safe. Maybe we were lulled into a sense of American security, that America is finally going to be the different place. So, particularly for us it’s been difficult. Think for America, it doesn’t feel like this is us, it’s not who we are as Americans.

I’m not sure how we get out of this, except I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of what maybe has brought us to this place. Evil and goodness are part of our human experience. There are evil acts, there are good acts. There’s evil people, there are good people and a lot of times each of us have both within us. What has maybe generated this feeling that this is changing is that evil words and thoughts have been weaponized through the media, through leadership that does not try to bring the upward reach again, that evil acts that have been pretty much kept in the dark corners of America are now much more open because again, words have been weaponized to create that.

What gives me hope is that what we can do is learn to weaponize goodness and what I’ve noticed throughout the pain, the suffering and the Jewish communities have gone through in America is the outpouring of love. Incredible acts, not just of people picking up the phone or emailing or private messaging, but simple acts of kindness that we’re experiencing here in West Virginia.

When we had a joint service at the temple in the synagogue, people from the Christian community, the Muslim community, people all faiths, no faiths, ask if they could just come and quietly be with us. Sunday morning, the day after the massacre, I was at synagogue, we were at services and like most of us, we were thinking ‘it could have happened here.’ We walked out and there was a bouquet of flowers. We don’t know who left it. Someone took a picture of it, of actually the family, and that person told me that the little children were deciding where to put it and the parents were there. That’s the simple act of goodness that needs to be weaponized. So, I posted that on social media. When people saw that, that brought tremendous comfort to people. Other people started doing other acts.

Just as words can become weaponized and create evil acts, goodness can be weaponized through social media as well. One of the things I’m thinking of is that there’s two ways that we get out of problems: one is top-down and the other one is bottom-up. Top-down would be leadership. Our country is filled with different cultures, different experiences and we’re a divided country. We’re a divisive country at times. We have a robust discussion about politics, about religion, about everything. And yet, whenever it got a little too hostile, leaders led.

Leaders from the top-down, brought us together, united us and reminded us of our better angels. And that’s not happening, so maybe it’s time for the other way and that is bottom-up. We need a movement of goodness and we can weaponize that. Maybe that’s our obligation. That’s what we owe America because that is what American is all about.

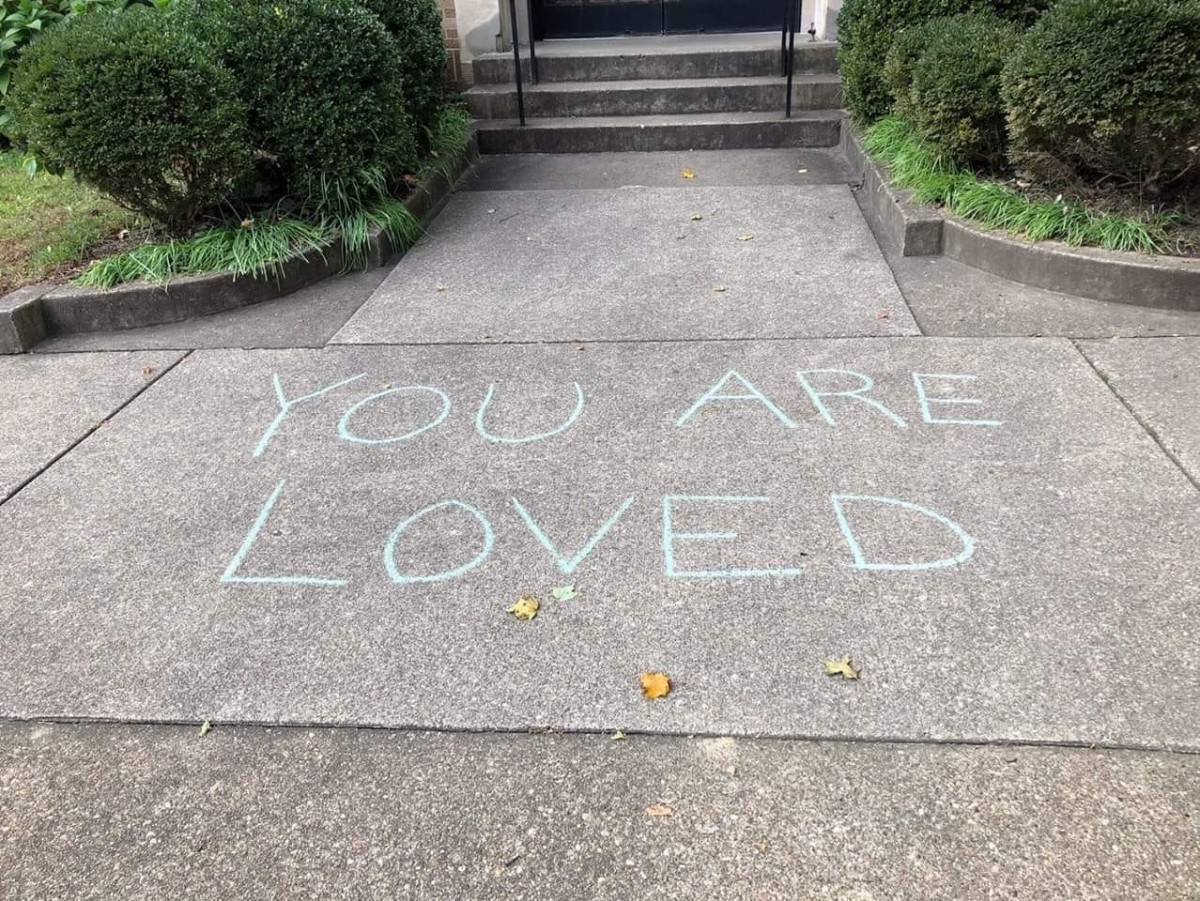

At the B’Nai Sholom congregation in Huntington, someone had drawn graffiti on the sidewalk. Usually when you hear graffiti by a synagogue, you think ‘uh oh swastika,’ but it was the words ‘you are loved.’ It’s already been shared like 130 times. Again, that’s weaponizing goodness. That is taking good acts because that’s what America is all about. That’s what people are all about. Yeah, we have evil thoughts and yes sometimes it translates into evil acts, but that’s always been controlled and it’s always been brought back into that evil bottle through leaders or through people that talk properly. It’s not happening today.

RT: You mentioned, when there was service on Sunday that there were thoughts of ‘could this happen here?’ Have there been discussions about changing any of the security measures at the temple?

VU: Unfortunately, the idea of securing our places of worship is not new experience. It’s been going on for quite a while in America, which is sad. It’s not just synagogues, it’s also mosques and churches. These places are supposed to be places of entry, where people that are lost, broken-hearted know that the door is open. That hurts. That hurts me that we need to rethink how places of worship should be. Our synagogue has always been open. Pretty much 6 a.m. morning to 6 p.m., you can just walk right in. It didn’t make a difference and you were welcomed. That’s the way churches were, that’s the way mosques were and now unfortunately, that’s been shattered. We’ve been needing to and we continue to upgrade our security and unfortunately because of this incident, we’re rethinking it again and where our critical needs are now.

RT: We’ve talked in the past about parts of the Jewish faith being welcoming to the stranger and how I know you’ve been involved with refugee resettlement and that was sort of an issue that maybe was on the mind of this shooter, has that issue come up again? Do you feel more committed, just as committed to that cause now?

VU: The shooter talked about one of the reasons that he was going to do what he did was not just because it was a hate crime and not just because they were Jews and not just because of Jewish ideas, but Jewish ideals and broadening that into Christian ideals, Muslim ideals. Ideals that all of humanity share and that is to welcome the stranger. That bothered him. He was worried that America is being invaded.

That’s when the words were being weaponized by the top-down that these caravans are coming and who are supporting it? The Jews. The Jews are supporting this type of refugee resettlement, open immigration. Hate can’t win. Evil should not win and evil will not win.

After I found out about what happened, it made me want to go to synagogue more. It made me want to help resettle refugees one day in West Virginia more. It made me very proud that I’m an immigrant to this country more.

Far from frightening me and others who are so dedicated to the idea that the American experience is this huge melting pot that grows with our diversity. In some ways, ironically, he failed because he is going to be known as someone who has energized the immigration movement, the refugee resettlement movement, the Jewish people.

I was very touched actually that the first responders that took care of him in the hospital were all Jews and they knew who he was. That speaks of humanity, and that’s what we’re all about. That’s weaponizing goodness. That is taking goodness and spreading it and showing it. That’s what God would want us to be. Not filled with hate, but always filled with goodness.

This interview was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.