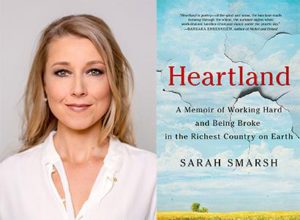

With equal quantities of truth and empathy, the book Heartland reveals the stories of the rural working class. But Sarah Smarsh isn’t fighting for her tribe, she’s building bridges across America’s wcultural and politics divides.

Sarah Smarsh is a unique and prophetic voice in American journalism.

Smarsh tells the convincing and compelling story about her fifth-generation Kansas farming family in her first book, Heartland, A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth (Simon and Schuster). She introduces us to remarkable women like her grandmother Betty, who escapes the violent grasp of a husband who once shot her. Betty works through an endless string of jobs until becoming a parole officer, working at a county courthouse, the only woman to occupy that position. The images from these stories are unforgettable – Betty dancing on the kitchen table or holding on to Sarah and a beer as Arnie, her husband, takes them on a precarious sledding spin through the Kansas winter snow. Jeannie, Sarah’s mother, is a beautiful, intelligent yet distant figure who struggles with the effects of working class poverty’s challenge for women – teenage pregnancy. Sarah was born when her mom, Jeannie, was 17 years old. Jeannie was born when her mom, Betty, was 16 years old.

I watched Sarah Smarsh interviewed on PBS’s Amanpour & Co. about her long journey from childhood poverty to being a successful writer for publications like the New York Times and the Guardian. Michel Martin asked, “Do you feel like you made it?” Smarsh responded, “I feel, you know, the day that I graduated from high school being the first person from my farmhouse to do so, I remember at that moment and I think I might even write about this thinking I’m not pregnant and I graduated from high school. I made it.”

Of many characters in this book, Smarsh herself is one of the most compelling, from a curious questioning child to a resilient college student working three jobs to graduate from the University of Kansas. Often Smarsh talks to August, her imagined child, that she might have had as a teenager. The technique works and reminds the reader that this writer has lived in two very different worlds and that she will not give up on either one.

These stories are told honestly and forthrightly. One senses that Smarsh aims above all to tell the truth, but that the truth can only be uncovered with empathy. The people she writes about are not caricature heroes who rise above it all to show us what character is about. Many are tough and resilient, yet flawed. A few are violent and ruthless. Smarsh is grateful that the men in her life, her grandfather-in-law, Arnie, and her father, Nick, are not violent and that each has been an advocate for her. She writes about Arnie and her community after Arnie has died and his farm equipment is being auctioned off.

“Arnie was a good man,” the auctioneer said, his breath a white puff in the air. “Let’s give him a good sale.” Then he said numbers quickly, and the people in the crowd raised their hands to bid. They bid on things they didn’t need, because they knew the man they had belonged to and they knew his family who stood next to them now. In the greatest gesture of respect, they bid high. …. The country people pulled cash out of their billfolds with cold fingers. In a rare act, they had driven a price up, rather than down, and intentionally paid more than market value. They knew Arnie had done the same at other farm sales. They nodded at us as they helped one another load the pieces of our farm into their pickup beds. They knew what a person’s life was worth.”

As a writer, Sarah Smarsh has been a persistent voice for naming what Barbara Ehrenreich says on the back of the book is “America’s most taboo subject, which is class.” Smarsh puts it like this.

… [I]n my early adulthood, I don’t think I’d ever heard the term “white working class.” The experience it describes contains both racial privilege and economic disadvantage, which can exist simultaneously. This was an obvious, apolitical fact for those of us who lived that juxtaposition every day. But it seemed to make some people uneasy, as though our grievance put us in competition with poor people of other races. Wealthy white people, in particular, seemed to want to distance themselves from our place and our truth. Our struggles forced a question about America that many were not willing to face: If a person could go to work every day and still not be able to pay the bills and the reason wasn’t racism, what less articulated problem was afoot? When I was growing up, the United States had convinced itself that class didn’t exist here. ….. This lack of acknowledgement at once invalidated what we were experiencing and shamed us if we tried to express it. Class was not discussed, let alone understood. This meant that, for a child of my disposition – given to prodding every family secret, to sifting through old drawers for clues about the mysterious people I loved – everyday had the quiet underpinning of frustration. The defining feeling of my childhood was that of being told there wasn’t a problem when I knew damn well there was.

Smarsh knows that justice is not a zero-sum game. To name the suffering of one person is not to invalidate the suffering of another person from a different experience. Rather, by telling the stories of people without a voice is to humanize us all. Smarsh is a bridge builder between women and men, rural and urban, rich and poor. In our present moment of division and culture warfare this is where Smarsh is at her most prophetic. She is not fighting for her tribe. She is telling a story that connects human beings.

This article was originally published by Daily Yonder.