This story is part of a series of special reports titled “Work in Progress,” with support from Foothills Forum and Rappahannock News looking at the dynamics of changing agricultural economies. The story was originally published by Rappahannock News.

With many family farmers now senior citizens, agriculture in Rappahannock is heading into uncertain times

You can see it’s a story James Jenkins likes to tell.

It was a dozen or so years ago, and he was back in the big shed at Jenkins Orchard near Woodville, where customers still show up year after year to pick bags of apples or peaches or cherries. A stranger walked up, and, after confirming that he was talking to Mr. Jenkins himself, looked him straight in the eye and announced, “I’m here today to buy this place.”

Jenkins was taken aback, but managed to respond. “This place isn’t for sale.”

The stranger wasn’t done. “I’m going to make it so you don’t have to work the rest of your life.”

Jenkins wasn’t done, either. “Well, let me tell you something,” he said. “I’ve worked all my life, and I’m planning on working the rest of it.”

And, so far, he has. Now 69, James still spends long days out in the field, and jokes that if he did retire and sat down in a chair for any length of time, he’d probably need to be pried out it because his body would be so stiff. He’s proud that he’s been able to sustain the business his father started long ago. But he realizes that these days hard work isn’t enough, that the financial burden of farming in a place like Rappahannock is truly daunting, especially for someone just starting out.

Photo: Luke Christopher, Rappahannock News.

“If a young person wants to go out and try to farm, I don’t see it, at least not in the fruit business,” he said. “Unless he has a big stack of money.”

Jim Manwaring may be even more skeptical. He too is in his 60s; he too is maintaining a farm his dad built, Red Oak Ranch. But, unlike Jenkins, his is a cow-calf operation, comprising about 260 cows and 1,100 acres of pastureland.

“It’s now impossible to buy land in Rappahannock County and raise cattle and make a profit. Totally, utterly, completely impossible,” he said. “Think about the investment you would have to make. The only way a person could do it would be to inherit the land, or have someone like me say, ‘I’ve had enough. I don’t want to do this anymore.’ And, basically let them run cattle on the land to keep it in land-use.

Photo: Luke Christopher, Rappahannock News.

“But there just aren’t many young people getting into farming,” Manwaring added. “We’ve got kids and grandkids. I don’t want them getting into it.”

Do the numbers

Pessimism about the future of family farming in Rappahannock is just one piece of a larger puzzle. As the county transforms into more of a well-mowed retirement community, it’s confronted with a tangle of questions. Will the costs of providing services to an aging community — particularly for emergency care — strain the ability to pay for them primarily through property taxes? Does the comprehensive plan need to be more proactive in addressing shifting economic, technological and demographic demands, or is it just fine the way it is? How big a role should business and tourism play in shaping the county’s future? And, what can be done to ensure that more young people are part of that future?

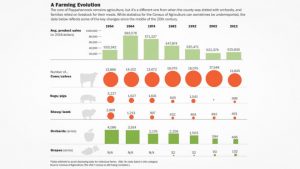

Agriculture, though, remains the linchpin, and the numbers there are disheartening. In 2012, according to the U.S. Census of Agriculture — 2017 figures are still being compiled — farms here lost an average of just under $6,000. The revenue generated through the sale of farm products averaged $23,377 per farm. That’s not even $10,000 more than the average in 1974, which was just under $14,000. Adjusted for inflation, it’s a huge drop-off. That per-farm average of $14,000 in revenue in 1974 would have been equal to $68,000 in 2012.

At the same time, the cost of farmland has shot up to staggering levels. The average cost of an acre in 2012 was $8,443, a jump of almost 130 percent in a decade and nearly 200 percent since 1992. It’s worth noting that depending on the location, water access and the view, the price per acre in Rappahannock varies widely. Last year, the lowest price per acre was $2,540. But two lots sold at $10,000 an acre.

The expense of running a farm likewise has climbed dramatically. A new tractor alone can cost close to $100,000. There are constant outlays for insurance and maintenance, not to mention hiring workers during busy times. Those who sell their products on commodity markets, rather than directly to consumers, operate on particularly thin margins.

“The two things that matter to a farmer are the weather and the market price,” Manwaring noted. “And those are the two things you have no control over.”

The number of farms in Rappahannock in 2012 dropped to 397 — almost 50 fewer than in 2002. Overall, about 63,000 acres — or roughly 37 percent of the county — was in farmland in 2012. The figure was 51 percent in 1982.

The nature of the farms has changed, too. They are smaller — the average size in 2012 was 158 acres, about half as big as in 1969. A growing number are what old-timers refer to as “city farms” or “hobby farms” — parcels where owners grow only hay or raise enough crops or livestock to qualify for land-use deductions on their property taxes. Any agricultural property that generates at least $1,000 a year in gross sales is considered a farm by both the Census of Agriculture and the state’s land-use program.

That could help explain why the average revenue figures for Rappahannock’s farms have remained low; owners of many such “hobby farms” have other sources of income. In fact, longtime farmers will tell you that the number of people in the county making a living solely through farming can be counted on two hands. Maybe one.

Manwaring put it bluntly: “There’s no other industry in the world that would accept the return on investment that you have in farming.”

Farming as viewscape

Back in January, on an unseasonably balmy Saturday afternoon, about 100 people packed the Washington Fire Hall. Many were farmers, others were residents tied to food production or related businesses. It was billed as a workshop, but it was really more of a conversation starter. The subject was one of the county’s more pressing challenges: How to sustain farming in Rappahannock.

Guest speaker John Piotti, executive director of the American Farmland Trust (AFT), pointed out that the rest of rural America faces the same dilemma. U.S. farmland is disappearing at an accelerating pace. By AFT’s estimate, it’s being lost at a rate of 120 acres per hour, or about a million acres a year. It’s estimated that 370 million acres of U.S. farmland will be in transition in the coming decade. A big reason is that, as in Rappahannock, a lot of U.S. farmers are now in their 60s. More than 62 percent were older than 55 in 2012 — the most recent year for which agriculture census data is available — with the largest age group then between 55 and 64.

The deeper purpose of the January session, though, was to sharpen the focus on both the potential consequences and the opportunities of an agricultural community in transition, one going through not just a demographic change, but also facing the prospect of a future different from what family farms have been doing in Rappahannock for a long time.

At the heart of the discussion that followed was the matter of where the county’s future farmers will come from, and the hurdles they will face, including the challenge of working out leasing arrangements with landowners. It can be a difficult process, one often complicated by painfully different expectations.

“To some people, the aesthetics of farmland is more important than the productivity of farmland,” said Mike Peterson, who, with his wife, Molly, had become the poster couple of Rappahannock’s young farmers. But after 10 years of running a cow-calf operation on leased land in different parts of the county, they called it quits this spring and moved to Pocantico Hills, N.Y., where Mike now works at the Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture.

Casey Gustowarow, who, with his wife, Stacey Carlberg, manages The Farm at Sunnyside, agreed that farmers and the people whose land they want to farm can have contrary notions about what’s involved. “People will say, ‘Yeah, I want to have farming on my land,’ but don’t always understand what that means. You may have to put up a tunnel structure or a greenhouse, and they’ll say, ‘I didn’t think about that. I want the pretty viewscape.’”

The match game

Then there’s the matter of income projections. “The challenge comes when the landowner thinks the land is worth more than it really is from a farm standpoint,” said Ron Saacke, coordinator of the Young Farmers program at the Virginia Farm Bureau. “Or the landowner doesn’t give the farmer the flexibility to do the kind of agriculture they can do or need to do to build their business.”

Saacke oversees a Virginia Department of Agriculture program called Farm Link, which is designed to connect farmers facing retirement or landowners who want to keep their land in production with beginning or expanding farmers looking for land to buy or lease. He conceded that the program has been underused and isn’t particularly well known. Saacke also noted that landowners initially were discouraged to find that many of the “farm seekers” had little or no farming experience.

So the program created a category of “certified farm seekers,” requiring that they have both experience and a business plan. But the number of participants has remained small. Currently, only 23 landowners and nine certified farm seekers appear on the Virginia map on the Farm Link website. None is in Rappahannock County.

Saacke said the program hasn’t been able to track the long-term effectiveness of connections it may have made, although he believes “only a handful of folks” are still farming land they found through Farm Link. “The challenge of farming,” he added, “is that you don’t really know if you’ve had a successful business unless you’ve been in it for many years.”

Photo: Luke Christopher, Rappahannock News.

Market strategies

That kind of uncertainty clouds the future of farming itself. Not even Kenner Love, who, as the county’s agriculture extension agent, focuses on the state of farming here, can predict with confidence where it’s headed. But he does see the trends — that U.S. farms selling on the commodity market are getting larger, not smaller.

The increasing fragmentation of farmland, however, has made it much more difficult for a cow-calf operation to find contiguous parcels to expand its grazing acreage. Love said that to make close to the average Virginia family income of $55,000, a farmer would need to have about 300 cows, and that could require roughly 1,000 acres of land. “Where does a farmer in the county find a parcel large enough to support an operation of 300 cows?” he said.

Instead, as older farmers sell off parcels, the trend is likely to be toward more specialized farms emphasizing the sale of products directly to consumers — an approach that comes with less precarious profit margins.

Not that it’s a formula for fortune. “There’s only so much room for niche markets, too,” Love noted. “Every community within a 75-mile radius around D.C. assumes the metro area can provide a sustainable market. So, our farms are competing with farmers from Maryland, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Delaware facing the same dilemma.”

“People say we have this great market nearby,” he said. “We don’t have a market, we have people.” Love believes there’s a need for more precisely focused market analysis that identifies the tastes and demands of narrow market segments. “We need to have a better idea of what people in those segments are consuming in that market — varieties, types of foods, quantities of food. And, can we grow those foods here?”

Two farm operations that have successfully tapped into the D.C. market are the Waterpenny Farm in Sperryville and The Farm at Sunnyside. For Waterpenny’s Rachel Bynum and Eric Plaksin, it means loading up a truck with vegetables on weekends and driving to two of the more popular farmers’ markets just outside D.C. — in Arlington and Takoma Park, Md.

That accounts for the bulk of Waterpenny’s income, Bynum noted. “We didn’t come to Rappahannock expecting to have much local business,” she said. “This is a tiny place. Even if everyone in Sperryville bought all their vegetables from us, we couldn’t make an income to support our family, have health insurance, maintain our vehicles.”

It’s a similar strategy at The Farm at Sunnyside. About 75 percent of its farm income comes from selling its many varieties of vegetables at weekend markets in D.C.’s Dupont Circle, in Reston and here in the Town of Washington. But that’s now a tough model to mimic.

“I’m hesitant to say that everyone should farm this way, and that it works to go to farmers’ markets and make all your money there,” said Sunnyside’s Stacey Carlberg. “We’re in some of the best markets in the region, and now not everyone can get into those markets.”

Another reality is that food buying habits have changed. “We’re not seeing a lot of people buying their groceries for the week,” said Bynum. “Now, they can go to a Monday market, a Wednesday market, a Saturday market.”

An enticing alternative would be to supply food products to a regional retailer, such as Wegmans. But that would require a scale of production far beyond what any local farm is capable of maintaining, particularly those in the livestock business. “We’ve got a few people who could sell off 10 animals a month,” said Mike Sands, who operates Bean Hollow Grassfed near Flint Hill. “But for something like the regional Wegmans, you’d need to be at 100 animals a week.” Love pointed out another complication for those growing produce. “You don’t just need to have volume. Fruit in supermarkets has to be a certain size, a certain color, and have a certain type of packaging. If you can’t do all that, they don’t want you.”

A global business

In short, the path to prosperity for Rappahannock farmers is, perhaps more than ever, an obstacle course. And yet, John Genho remains upbeat about the future of agriculture here. As general manager of Eldon Farms near Woodville, he oversees an operation covering 7,100 acres that sells about 600 cows and calves a year to be fattened in Midwest feedlots. He still believes in the staying power of what’s long been Rappahannock’s greatest asset — its land.

“I’m optimistic,” he said. “There will be a period of transition, and it may be uncomfortable for some people. But there’s open space here. We have grass that produces protein and allows animals to graze through the winter. Minnesota doesn’t. We’re going to keep doing that in one form or another. It will get sorted out. People will figure out how to make a living off agriculture.”

That, however, may require a different way of doing business. Genho said that as much as he respects the traditions farm families have passed on, they can make it more difficult to adjust to what is now a complex and competitive global industry.

“When someone raises oil prices, that impacts me and my cows here,” he said. “Thinking that I can cut all those ties and be insular, that’s not the solution. You need to realize you’re part of something bigger.

“It has to be viewed as a business. If I were to run any other business the way my grandfather ran his business, it would probably fail. If you’re feeding your cows hay 120 days a year because grandpa fed hay 120 days a year, you’re probably not being as efficient as you could be.”

Genho said one lesson the staff at Eldon Farms has learned is that in today’s agriculture economy, bigger is not always better, and more can mean less when it comes to revenue. “As farmers, we tend to go for the biological optimum,” he said. “You think, ‘I want the biggest calves, the most calves per acre. I want the most cows pregnant.’ But the unit of success isn’t necessarily pounds of calf. It’s dollars.”

Old school

That’s not to say that local farmers who still hold on to some of the old ways can’t succeed. James Jenkins proudly declares himself “old school.” He still doesn’t accept credit cards. Jenkins Orchard is the same cash-or-check business it’s always been. He describes his work as a “5 to 9 job” (that’s 5 a.m. to 9 p.m.) and acknowledges that not many people these days want to work that hard.

“When I grew up, if you didn’t work, you didn’t eat. We came up hard,” he said. “But honestly, if I went up the road and asked a 16-year-old kid if he wanted to work on weekends, he’d be insulted, probably. That’s the way things are.”

On the other side of the county, at Williams Orchard on Ben Venue Road, Eddie Williams feels some of the same exasperation. Like Jenkins, he’s from a generation that grew up when every farm had an orchard and now is facing retirement when every kid has a cell phone.

Williams isn’t exactly impressed with the work ethic of young people today (“It stinks.”) He still relies largely on word-of-mouth to get customers to come out to the orchard. On a nice fall weekend, as many as 160 people show up, he said.

But business isn’t like it once was, back in the day before I-66, when farmers set up roadside stands to sell apples to tourists stuck in the backups on 211. When even locals without an orchard joined in apple-picking to earn some extra money for Christmas. Or, when customers went home with bushels of apples they’d store in their cellars, not just a single bag.

“People now are so pressed for time,” he said. “They have groceries delivered to them when they live 20 minutes from a store. So, how do you convince people to make an hour-and-a-half drive to buy a few pieces of fruit?”

For Williams, farming was a way of life before it became a business. He did his “apprenticeship” under his father for 16 years. “Farming was like an addiction,” he said. “All I saw was the work and what needed to be done. I didn’t really start thinking about the money until I was in my 40s.”

Despite how much has changed in his business — including that people are eating fewer apples — Williams believes a younger farmer in Rappahannock could still make it by doing what he’s done.

“They may not prosper, but they’ll survive.” he said. But his own life has taught him that it won’t come easy.

“Everybody makes mistakes, but if you make a mistake as a farmer, you pay for them really hard.

“Rappahannock County is a great place to live,” he said. “It’s just a hard place to make a living.”

This article was originally published by Rappahannock News.