Karen Frey is dressed head to toe in mementoes of the 2016 election. Offering cookies on a platter to passersby from beneath a tent outside a shopping plaza, she wears tennis shoes bearing “Trump” logos. She bought them online.

Her hoodie reads, “Deplorables Club Est. 2016 Lifetime Member.” The words circle an emblem of a basket. Her bright red hat says, “Make the Slate Belt Great Again,” a localized version of Donald Trump’s ubiquitous slogan.

This is the “Slate Belt,” a small chain of towns in Northeastern Pennsylvania where slate mining was once a key industry. If you could turn Trump’s unforeseen victory in 2016 into a Halloween costume, Frey is wearing it.

An organizer in several local Republican organizations, Frey is a grandmother, but she’s spritely. She moves around, greeting fellow activists, and stops to reposition a sign barring pictures of Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor and his running mate under the words “For a More Socialist PA.”

Two years ago, this town, Mount Bethel, was dotted with Trump yard signs, recalls Chadd Horton, a fellow organizer.

“You started to see them pick up when the other candidates left the [primary] race,” he says, and they kept accumulating. Trump carved his unpredicted path to the White House through such de-industrialized patches of the Rust Belt.

Frey is out to convince her neighbors to vote Republican in the midterm elections on Nov. 6 to support Trump’s agenda. “They might not like how he says things and words things,” she says, “but the overall rating of what [Pres. Trump] is doing is making people understand he’s doing the job he said he was going to do for us.”

A Republican Looks to Beat the Odds

The congressional candidate at this meet-and-greet, Marty Nothstein, is also wearing a reminder of the recent past — his own. Tall and slim, he circulates through the crowd in a Team USA jacket.

A native son of the Lehigh Valley, Nothstein, 47, was an Olympic cyclist. In his pocket, he carries the gold medal he won in Sydney in 2000. He’s ready to show it to potential voters. It leaves a lasting impression.

Since retirement, he has lead a local cycling organization, run a farm and served on the Lehigh County Board of Commissioners, his first elected office.

But Nothstein walks a line when it comes to Trump.

“As an elected official in this district, you’re a check and balance on the president no matter who he is or what side he’s on,” he says, “and he’s done some good things for this district, but he’s done some things I don’t agree with.”

He is pleased with the economy, but he’s critical of government spending under Trump and the president’s dismissal of Russian election interference. “[I]f our intelligence officers are saying Russian is doing something,” Nothstein says, “I tend to believe them.”

As a cyclist, Nothstein earned the nickname “The Blade” for weaving in out of the pack, cutting ahead of opponents to win narrow victories. He will have to pull off some equally skilled political maneuvering to win an election that changed mid-cycle to favor his opponent, former Allentown City Solicitor Susan Wild, a progressive Democrat.

The New 7th

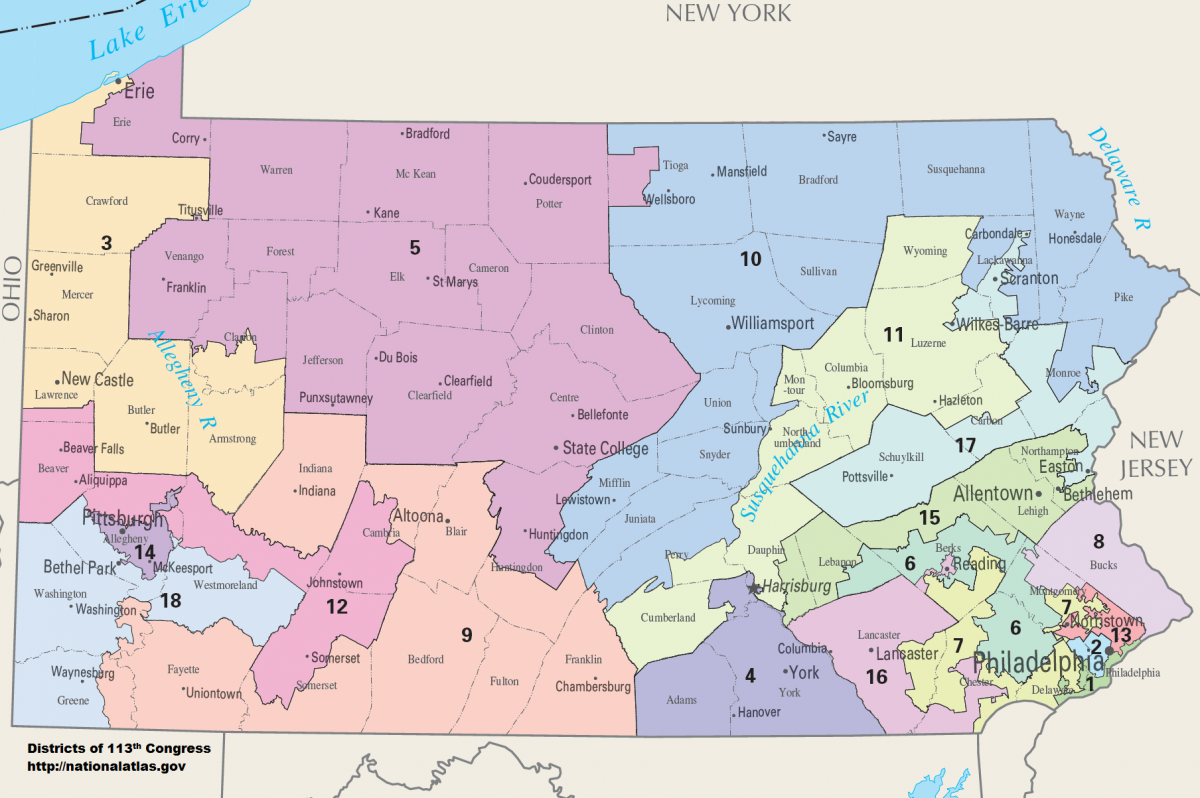

Pennsylvania was a key state to Trump’s triumph and in 2016, it also sent 13 Republican congressmen to Washington, out of its 18 seats. Two years later, the Democrats have the wind at their back; the party in power usually loses seats in midterms, but Republicans in Pennsylvania had the advantage of a congressional district map considered one of the most gerrymandered and GOP-friendly in the nation. Suburbs and small cities were welded to rural, conservative voting blocs through sprawling, curling shapes and contortions.

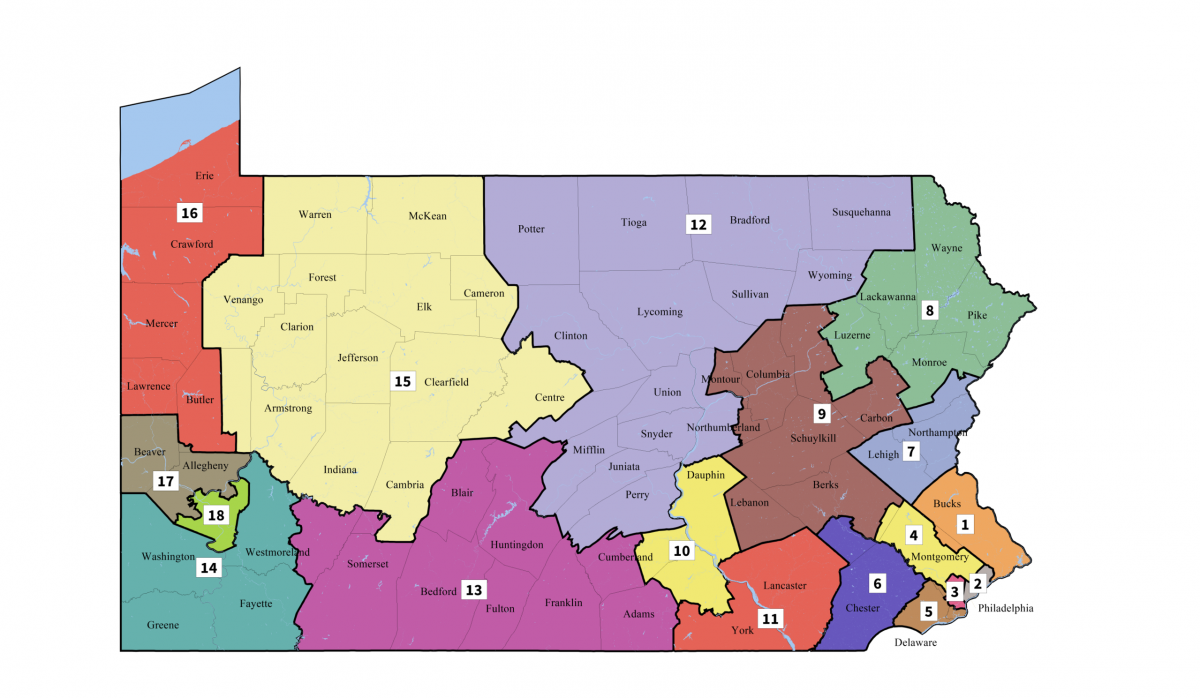

Early this year, the state Supreme Court overturned that district map. The new one replaced Republican-safe districts with competitive ones, and this year, Democrats have the chance to even out Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation, contributing to a possible party takeover of the U.S. House of Representatives.

When Nothstein entered the primary in October of 2017, he was running in the 15th district, which retiring Republican Charlie Dent had won by at least 10 points since 2004. The 15th was a wrench-shaped mass that extended 80 miles across, from the eastern state line almost to Harrisburg. Nothstein was redistricted into the new 7th, centered on the small but growing city of Allentown– population 121,283.

“It’s a purple district,” Nothstein admits. “It depends where you’re at. It depends on what neighborhood you’re in.”

Take all the votes cast in the towns and cities that make up the new 7th and in 2016, Hillary Clinton would have narrowly won it. In this election, Democrat Susan Wild has a 3-to-1 advantage in cash and leads Nothstein by seven or eight points in recent polls.

Six of the new districts are competitive, but the 7th “is about as even as you will find,” ideologically, says Christopher Borick, professor of political science at Muhlenberg College in Allentown and director of its Institute of Public Opinion.

It’s also an area in transition. Billy Joel eulogized Allentown in his 1982 ode to the dying Rust Belt, named after the city. Allentown was where “they’re closing all the factories down” and neighboring Bethlehem was where “they’re killing time, filling out forms.” Now, Allentown is the fastest-growing city in Pennsylvania and urban planners predict more than a million people will move to the Lehigh Valley by 2040. Fueling the population growth are jobs in healthcare and office support, affordability to retirees and empty-nesters and a wave of Latino migrants.

The 7th is “a little of everything,” says Borick. “It’s a little microcosm of the entire state. It has cities. It has suburban and rural areas. It’s a beautifully competitive area and it had been ripped apart by the old lines.”

Pennsylvania’s Gerrymandered Past

In 2011, Republicans, in charge of the state House and Senate and the governor’s office, redrew Pennsylvania’s congressional map. Those districts became infamous for their squigglies, hammerheads and claws. One outside Philadelphia was dubbed “Goofy kicking Donald Duck” and became emblematic of party-rigging of district lines.

The effort was nakedly partisan, says Borick.

“The visuals tell the story,” he says. “The tortured nature of the map was a glaring effort to squeeze the competitiveness out of the state.”

Pennsylvania’s urban centers are Democratic strongholds and its rural expanses lean heavily Republican. But some areas should be “naturally competitive,” says Borick– those encompassing small cities, like Erie and Allentown, and the suburbs of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Under the 2011 map, those places were sewn to rural voting blocs. In 2012, Democrats lost two seats, holding on to five, those centered on Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Scranton. Republicans took the rest. With one exception, every victor that year won by more than 10 points.

“That’s not natural to the makeup of the state,” says Borick. Democrats have long lead Republicans in voter registration in Pennsylvania, about 4 million to 3 million.

In January, the League of Women Voters initiated a lawsuit challenging the old congressional map, dubbing it “the worst partisan gerrymander in Pennsylvania’s history and among the worst in American history.” The state Supreme Court agreed that it “clearly, plainly and palpably violates the [state] Constitution.”

The court tasked state legislators with creating a new map. Instead, Republican lawmakers fought the decision, unsuccessfully petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. They missed deadlines to create a new map, so the court brought in a Stanford Law School professor with an expertise in redistricting to draw the districts. He tried tried to avoid breaking apart counties and created districts in neater geographical clusters.

State Republican leaders contend the court acted with ill intent and outside its constitutional boundaries. “This entire exercise, while cloaked in ‘litigation,’ is and has been nothing more than the ultimate partisan gerrymander,” stated Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati and House Speaker Mike Turzai in a joint statement. (Neither responded to emails requesting an interview for this article.)

As they ran out of options, the new districts took effect for May primaries and shifted the ground beneath candidates’ feet.

The New Districts and Their New Races

Several Republicans in the old 15th district wanted to replace Dent in the House. Candidates were districted out of the race when it changed or “got cold feet” about its competitiveness, says Nothstein. That left him and Lehigh County Commissioner Dean Browning. In another razor-thin victory for The Blade, Nothstein won by 300 votes.

In the Democratic primary, Northampton County District Attorney John Morganelli was an early frontrunner. Morganelli seemed to be making a play for Trump voters. He tweeted at the president for help on immigration enforcement and wrote in a Facebook post announcing his candidacy, “[T]his is not a liberal district and it fits my moderate profile well.”

Given the president’s hold over rural Pennsylvania, that seemed like a good strategy, even for a Democrat. Then redistricting shaved off a long stretch of mid-state voters.

Several candidates challenged Morganelli from the left. Progressives gravitated towards Wild. She eked out a victory with 33 percent of the votes (15,262) to Morganelli’s 30 percent (13,754). Wild stands against nearly every Trump policy and prerogative.

A Democrat Speaks With Urgency, But Not About Donald Trump

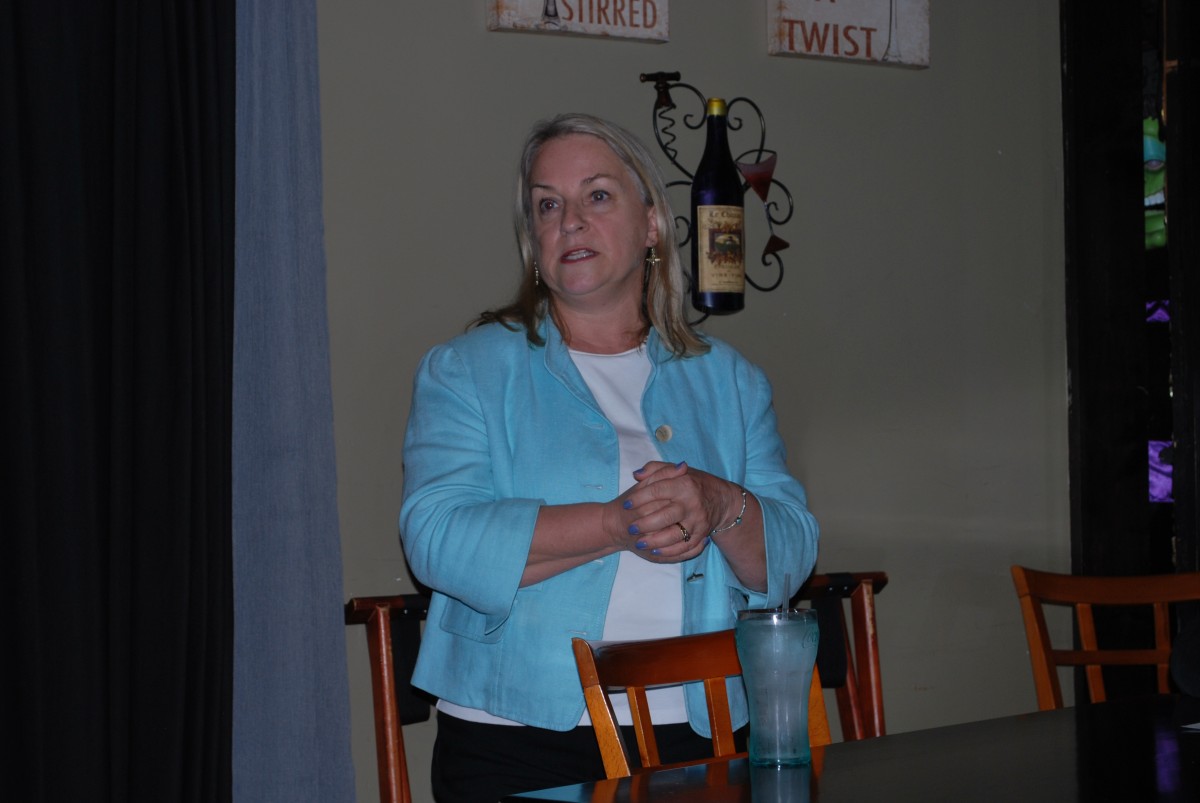

“I’m Susan Wild. I’m 61 years old. I’ve been practicing law in the Lehigh Valley here for 30 years. I moved here in 1988 for what was supposed to be two years and here I am.”

Wild is speaking to a room of small business owners at the Shanty on 19th, a bar/restaurant in Allentown’s liveliest neighborhood, the West End, centered on the old Civic Theatre. She wears a light blue blazer and her blond hair sits on her shoulders

She recounts growing up in a working-class family and taking out a federal loan for law school. The interest rate was one percent.

“I tell you all because it exemplifies what our government used to do,” Wild says. “It used to invest in its people.” She laments that recent graduates have “monstrous student loans that look like mortgages on a house.”

“There once was this concept of good government,” she says. “Not government that gives you handouts, but government [that] gives you a hand-up and helps its people who are not the uber-rich, not the one percent, not corporations, but ordinary people who struggle to pay their bills.”

Wild got her start in government work as city solicitor, chief legal counsel for Allentown. She decided to run for congress to “stop being distressed,” she says in an interview. “I have two kids and I am worried about their future.”

Wild’s message is one of urgency, particularly on kitchen-table issues like debt, healthcare, wages, income inequality and what she sees as lack of governmental investment in ordinary citizens.

As for Trump?

“I don’t talk about Trump unless specifically asked,” she says. “People have opinions about the president I won’t be able to change.”

Christine Stazo, an insurance agent, and Lewis Eckert, owner of an Allentown hair salon called only The Salon, shared a table at the event.

Stazo describes herself as “very progressive.”

“I’m looking for somebody who is all in,” she says. “Charlie Dent was okay, but he was on the opposite side of the fence. I do believe it is time [for his seat] to go to a Democrat.”

Eckert is “more in the middle.” He has seen political issues infiltrate the salon he has owned for 20 years. Young people in the field wither under rising costs of living and student debt, he says.

“I just don’t know how somebody in their 20s who has gone to beauty school makes it.”

He is also aghast at Trump’s attitude about women, exemplified in the infamous Access Hollywood tape released in 2016 and the saga of Brett Cavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court.

“My life has been around women,” says Eckert. “Women have opened up to me about their sexual assaults.” He says they speak more openly — and anxiously — recently. “I think the subliminal message of MAGA is, ‘Let’s go back to the old days,’” says Eckert. “Let’s go back to Mad Men.

He says his ideal presidential candidate is Republican Ohio Gov. John Kasich. Eckert likes Kasich’s appearances on Anderson Cooper 360, a CNN show where he has often rebuked Trump. This election, he plans to vote for Wild.

The Pennsylvania Election Math

“Democrats will pick up three to five seats” in Pennsylvania, says Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College. The most assured wins are three districts in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Wild and Conor Lamb, running in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, are also “in a good position.”

In this complicated year, U.S. Rep. Lamb won a special election to replace Republican Tim Murphy, who resigned amidst a sex scandal, and was redistricted to a new district to face another sitting congressman, U.S. Rep. Keith Rothfus.

Madonna adds that the election cycle will probably add three or four women to the state’s currently all-male congressional delegation.

2016 was an anomaly in Pennsylvania, according to Madonna, because of Trump’s strong “Rust Belt strategy.” In 2018, voters will return to habits that narrowly favor Democrats, he says. He notes that Democratic incumbents in two statewide elections, Gov. Tom Wolf and Sen. Bob Casey, both seem safe.

“The Democrats are more motivated, but we are in uncharted territory,” Madonna says. “We’ll see if Republicans can close that enthusiasm gap.”

Out in the District, Democrats Feel Motivated

Judy Lapos of Bethlehem is waiting in line for ice cream at the Lehigh Valley Mall in Whitehall, Pennsylvania. In a sign of the area’s economic health, the mall has no empty storefronts at a time when malls, symbols of late 20th century middle-class prosperity, are dying.

Lapos voted for Trump.

“I thought he was strong,” she says. “I thought he was an ‘I-can-take-care-of-it’ kind of guy.” But she probably won’t vote in the midterms. “I just don’t know the candidates,” she says.

A few feet away, Riydenor Camara of Allentown has finished a meal at the food court and is chatting with his adult son. Camara says he doesn’t know who is running in the midterms, but he plans to vote for straight Democrat, which he has done since he became a U.S. citizen in 1998. Camara, who has dual citizenship in the U.S. and his native Brazil, says he’s motivated to vote against Trump. “I find him so stupid,” he says.

The 7th District, where Wild and Nothstein are facing off, extends to the foot of the Pocono Mountains. Stroudsburg, at the foot of those mountains, is an entry point for vacationers. Wineries, bars and eateries serve residents and visitors. On a sunny October day, people there are still enjoying sidewalk tables.

Tony Cuttitta, a psychotherapist out for a walk, bristles at the mention of Trump.

“We have a president who has a bent towards an authoritarian streak,” he says. “He is a criminal. He did collude with the Russians.” Events like the violent calamity in Charlottesville, Virginia, have him fearing “a civil war.” He plans to vote straight Democratic.

Aubrey Levy, catching up with a friend outside Café Duet, says that Trump’s victory inspired her to increase her involvement in politics. A Democrat, she ran for mayor in her borough, Delaware Water Gap, population 746. She lost, but found the experience “challenging and fun.” Her main voting motivation is “women’s rights.”

“We need to protect those now,” she says. A constituent in the 7th, she plans to vote for all Democrats on the ballot.

When her companion says he doesn’t plan to vote, Levy exclaims, “I’m totally going to kick your ass.”

Swing districts, such as the ones bestowed on Pennsylvania by the state Supreme Court, could put Democrats in control of the U.S. House, stalling Trump’s agenda and altering the course of the nation. These political middle grounds, which pop up across the country, are exciting for that reason. But there is a downside to living in a mixed-ideology area.

Many people approached for this article declined to discuss their voting habits on the record, for concern neighbors and coworkers would judge them.

A woman who was also at Café Duet, eating lunch, in Stroudsburg plans on voting Democratic this year, which is usually how she votes.But this year, she doesn’t want anyone to know. She works as a fundraiser for an animal welfare organization and thinks Republicans might not give through her if they know her voting preference. She has lived in Stroudsburg all her life, more than 60 years, but says in the last few, she’s clammed up about politics.

“There is such an emphasis on us vs. them, me vs. you,” she says. “Most of us have the same concerns and worries, particularly about the economy…For some people, political affiliation governs everything they do.”

She says that ideology-biased news sources have pitted people against each other and sensationalized issues. “The news has been turned into a form of entertainment.” She remembers the days of high-school civics classes and when the entire country tuned in to hear one trusted voice, that of CBS Evening News’ Walter Cronkite.

“I think we need to go back to that,” she says, “instead of the cheap hysteria.”