This is the first of a two-part series on water infrastructure in Appalachia, and possible solutions to problems at the federal and local level.

The Problem

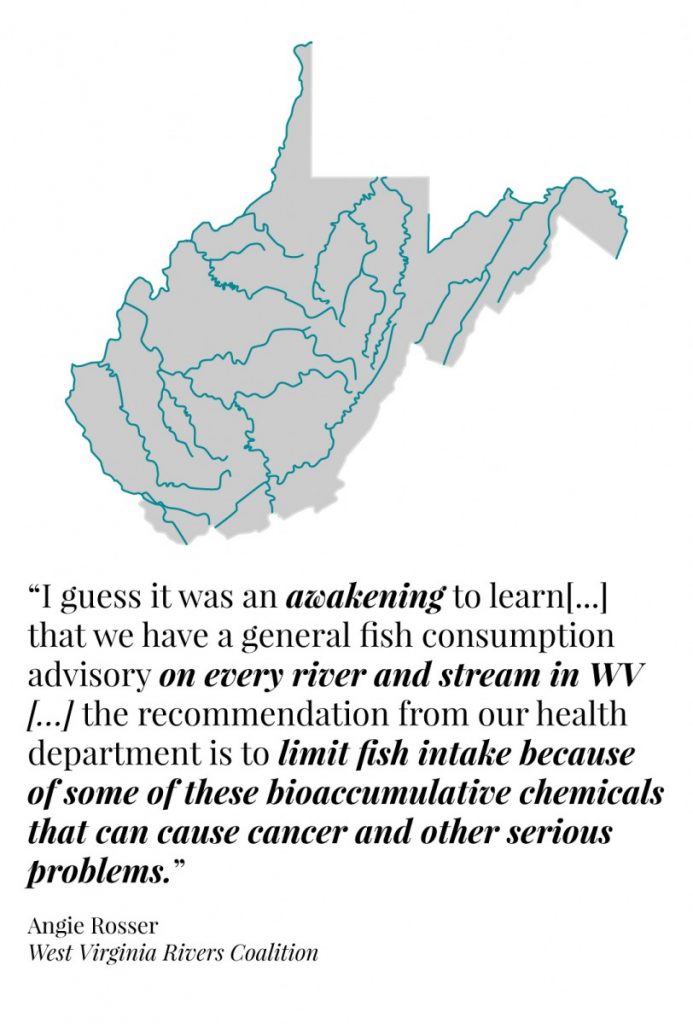

What West Virginia faces when it comes to its streams and rivers is a historically entangled knot of cultural pride, politics and industrial interests, Angie Rosser, the executive director at West Virginia Rivers, told me in a phone interview. The organization has been dedicated to monitoring and fighting for the water quality in West Virginia for over 30 years.

The same extractive and chemical industries that bring much-needed jobs and investment into this historically under-employed and over-exploited region also often carry with them environmental risks that materialize into illness and pollution, the causes of which are not only hard to fix, but often difficult to detect, or prove liability of in court.

The United Nations recognizes access to water and sanitation as one of our basic human rights. Yet there are places in Appalachia where that right is being indirectly infringed upon as a result of these extractive industries. Areas across Appalachia facing the most chronic water-safety threats include Martin County, Kentucky and Bladen County in North Carolina, where tap water in some communities can come out discolored and fetid — if it comes out at all.

The most infamous cases include the pollution of the mid-Ohio River Valley in West Virginia and Ohio, which houses a DuPont company factory that dumped an industrial chemical called C8, used to produce Teflon, contaminating the local water supply. The chemical has been connected to heart disease, birth defects and cancer.

In recent years, the Environmental Working Group — or EWG — a non-profit based in Washington, D.C., published a report that demonstrated a decades-long lack of enforcement on the part of the regulators and revealed that the agency’s “safety levels” might be misaligned to the real-world environmental damage they cause, meaning that in light of the latest research the levels once deemed safe may, in fact, be harmful.

April Keating, co-founder of Mountain Lakes Preservation Alliance, named south Upshur County, Doddridge County and her own area of the city of Buckhannon and the Buckhannon River as just couple of examples in West Virginia where she’s actively involved in remedying the effects of pollution from extractive industries, during her interview with 100 Days contributing reporter Emily Pelland.

Another case study is the Elk River spill of 2014 that affected over 300,000 people in nine West Virginia counties. At the time of the spill people, in the affected area were told to avoid coming into contact with the contaminated water and were banned from running their taps at home. The initial state of emergency issued by then-West Virginia Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin included advisory “NOT to ingest, cook, bathe, wash or boil water. Water in this coverage area (Boone, Cabell, Clay, Jackson, Kanawha, Lincoln, Logan, Putnam, and Roane counties) is okayed ONLY for flushing and fire protection.”

As these events unfolded, National Geographic published an article that revealed the lack of full understanding across the scientific community of the health impacts of the spill and unwillingness of the government to share the little that was known.

But even when dangerous contaminant levels are clearly identified, there is still the matter of difficulty in proving the liability to extractive industries for health problems among populations living close to their facilities.

Keating pointed to “what they (the industry) call nonpoint source pollution. You know it came from somewhere … you can’t pinpoint it exactly, and that’s what the industries are depending upon — because they know that you cannot go into court and definitively prove where it (the pollution) came from even though you live next door to that compressor station or you live next door to that separation plant.”

Water In Appalachia Needs a Trillion Dollar Solution from 100 Days on Vimeo.

The problem with water doesn’t start with pollutants and end with infrastructure. In between there is the way, in which the drinking water quality is being defined and how the results are being presented to the public — a complicated regulatory dance between protecting Appalachia’s water and protecting Appalachia’s industry. Meanwhile, flexibility in enforcement of standards can be subtle and varies by state.

To help draw attention to this complicated balance, EWG created a national Tap Water Database that makes it possible to research every zip code in America and check the water quality. In order to account for these gaps in regulatory legislation, the EWG decided to follow Public Health Goals. Originally from California, these more-strict safe drinking water standards provide safety levels for many more chemicals than the EPA’s regulations.

“The main thing is we don’t know what we don’t know, and there are thousands upon thousands of chemicals that are part of production processes that we don’t know enough about,” Rosser told me.

Keating pointed to over “750 chemicals that are used in fracking, many of which are carcinogens and endocrine disruptors and the heavy metals that come out of the earth.”

But even with proper research and monitoring, the challenges to water quality and infrastructure in West Virginia and Appalachia are many. Rosser pointed to heavy pollution from the extractive industries, a severe lack of sewage infrastructure in some areas — leading to “stray pipes” dumping raw sewage into the rivers, populating them with dangerous bacteria — and the chemical industry with its own brand of pollutants.

EWG’s Alex Formuzis explained that many of the Environmental Protection Agency’s drinking water standards that follow the Safe Drinking Water Act haven’t been updated in years.

The decades-long lag in the EPA updating the list of dangerous contaminants has resulted in a paradoxical situation, where a utility company could deliver contaminated water to its clients and yet still technically be in compliance with the EPA standards.

That very fact is an important factor when trying to understand the gap between what the data shows as utilities in compliance with the federal regulations, and then the health problems found disproportionately often among populations in certain areas, particularly in places rich in extractive or chemical and heavy industries.

I reached out to the EPA to comment on that claim. The agency responded by outlining a fairly complicated process of of reviewing and introducing new contaminants under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Here’s part of it: “The EPA must publish a list of contaminants that are known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and are not currently subject to EPA drinking water regulations every five years, EPA publishes draft CCLs (Contaminant Candidate Lists) for public comment and considers those prior to issuing final lists or regulatory determinations.”

The EPA’s official also stated that: “The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires EPA to review each national primary drinking water regulation at least once every six years and revise them, if appropriate. … EPA most recent Six-Year Review evaluated thousands of peer reviewed studies and millions of data points from drinking water treatment systems and was published in January 2017. The results of that review identified rules EPA can evaluate whether to modify to strengthen public health protection in future years. This review ensures that existing rules are offering the maximum public health benefit feasible.”

On its face, that appears to be a lot of active effort to keep those lists updated. EWG sees it differently. According to the group, despite the process being in place, it has failed to produce any new and substantive regulation. The 2008 EWG’s report stated that “the track record of the CCL program raises many reasons for concern, because in twelve years of this program’s existence, EPA has not developed drinking water standards for even a single chemical listed in the CCL.”

In an article, this time from 2016, EWG once again pointed to the EPA’s inability to “exercise its authority to protect public health from previously unregulated contaminants.”

The last Regulatory Determination for CLL 3, published in January of 2016, didn’t add any new chemicals to the list and postponed its final determination on one (strontium). The Regulatory Determination for CLL 4 is due in 2021. EWG recognizes some of the chemicals on the CLL 4 list (1,4-Dioxane; 1,2,3-trichloropropane, cyanotoxins, manganese, PFOA, PFOS, nitrosamines, pesticides, and hormones/endocrine disruptors) as potential risks to human health.

“Since 1996, EPA has been stuck in an endless loop of reviews, seemingly unable to set new standards for numerous contaminants found in drinking water. And without federal regulations, these contaminants continue to threaten the health of many millions of Americans,” author of the previously mentioned report and EWG’s senior science adviser, Olga Naidenko, told 100 Days in an email.

Here are some contamination issues of several zip codes across Appalachia we selected from the Environmental Working Group’s database. We chose to list results for both small and major water utilities.

Although our selection focused exclusively on Appalachian counties, the general pattern that emerged for the Appalachian states as a whole showed that in the case of nine of them (New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia) the utility companies with the highest number of violations were the ones serving the smallest communities, while for the remaining fours states (Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama) the same was true, but instead for medium sized communities.

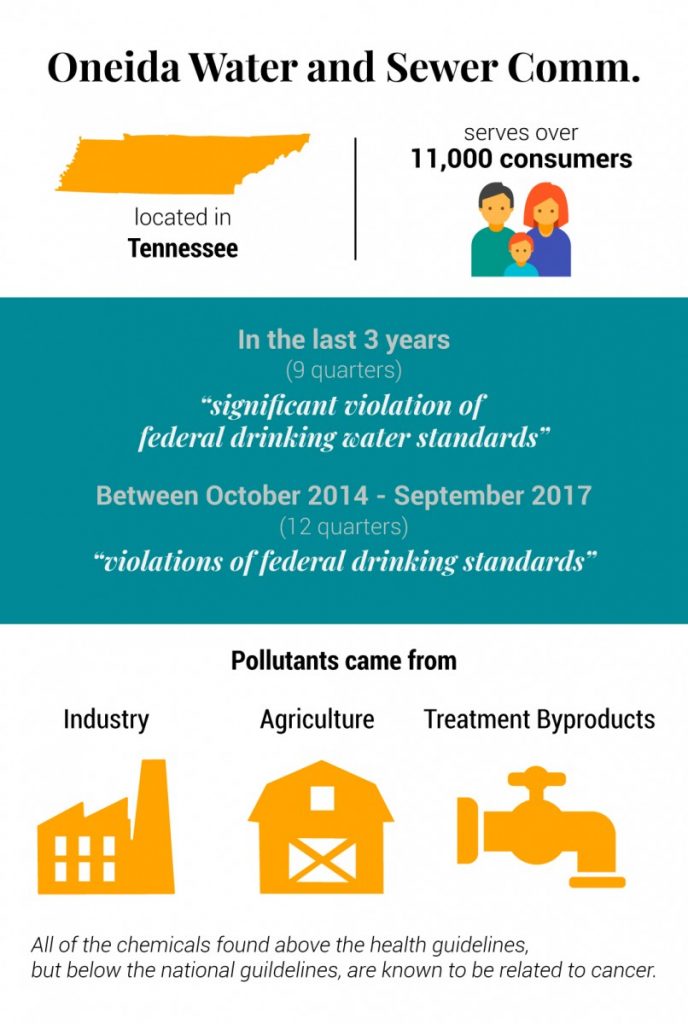

Let’s take a closer look at one example. Oneida Water and Sewer Comm. in Tennessee serves over 11,000 consumers. In the last three years, that specific water utility remained in “significant violation of federal drinking water standards” for the total of nine quarters, and from October 2014 to September 2017 it spent the total of 12 quarters with “violations of federal drinking standards.” The pollutants found in the water that exceeded health standards came from industry, agriculture or were treatment byproducts. All of the chemicals found were above the health guidelines, but below the national guidelines, are known to be related to cancer.

The rest of our selection can be found here.

The Fix

The people of Appalachia tend to value self reliance and, for the most part, manage to avoid the lure of outsiders promising false hopes. Many have accepted the price of living in an environment characterized by extreme costs, whether to their health or their surroundings, and extreme pay offs — to this day working in a mine remains among the highest paying jobs in the region. Rosser described it as a “fatalistic sense of place.”

She has met and talked to people who were outraged over the water infrastructure and water quality, but also exhausted and sick because of those very problems. ”I have stray sewage around me, but even me, working in this field, I try to put it ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ … because I don’t know what to do about it,” she said.

Mountainous populations are often spread out, making it harder to organize and muster mass movement around issues like this, even if they do affect one’s everyday life. Priorities come to a head when basic, immediate needs and more idealistic, long term issues are pitted against each other.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise then that the “Infrastructure Initiative” announced by the White House in February turned a lot of heads. The water infrastructure element occupies a prominent position within the proposal.

From flood management to waste water treatment facilities, the projects are supposed to be bolstered by the initiative in both direct funding and incentives for private industry to step up.

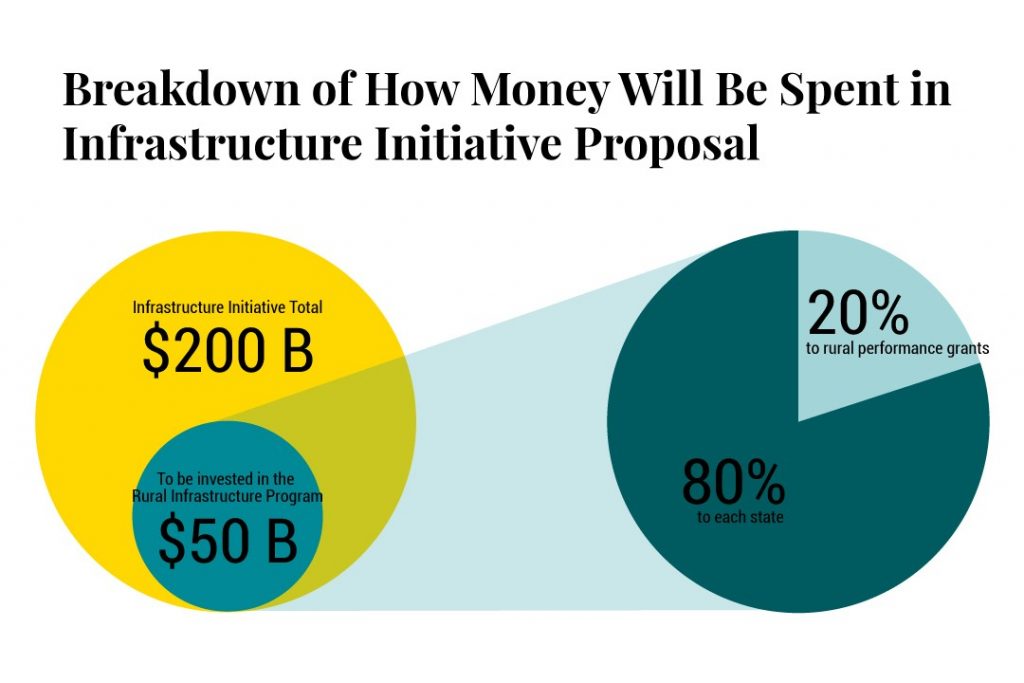

The $200 billion proposal is estimated by the White House to generate over $1.5 trillion of investment in American infrastructure. $50 billion of the entire federal pot of money is supposed to be funneled into rural America.

Water quality and infrastructure problems across Appalachia, particularly in the states with robust extractive industries and economies often based on boom-bust cycles, like West Virginia, Eastern Kentucky or Pennsylvania, are often intertwined with poverty.

“What I’ve seen and noticed and heard from others is that when you’re in a heavily mined community, you look around and there’s no other jobs, certainly no that pay $60,000 and upwards. … There are communities where water well becomes contaminated but then the company comes in and builds infrastructure for public water system,” Rossier told me.

Keating’s comments echoed that sentiment: “when you’re talking to regular people, it’s about jobs for them … When you’re talking to county commissions it’s about tax revenue … And when you have over 50 percent of the population living … at or below the poverty level, then you have an issue with people’s well-being that isn’t being addressed by the industries that they’re able to get jobs in.”

“So what happens in poor communities is that we were so focused on job creation that we’ll take anything that’s handed to us. We’ve been an extraction colony for over 150 years. It started with railroads and timber and then it went to coal and then it became gas.”

Some in Washington, D.C., including West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, question the likelihood of the proposal coming through. “We’re not seeing any money put into it … When you have $1.5 trillion of additional debt because of the tax cut, makes it hard to do anything, so we’re fighting and trying to make sure they’ll be able to (do it). I’ve got water and sewer needs, all over a very challenging terrain,” the senator told me during our brief conversation in late April.

The money dedicated to water infrastructure, and in the infrastructure proposal overall, is meant to encourage investment, meaning the $1.5 trillion is a projection, not hard cash that’s secured for rural America or Appalachia.

Out of the entire sum, the $50 billion would go to the Rural Infrastructure Program that would include all investments. Here’s how the funds from that pot would be distributed:

- 80 percent of the funds under the Rural Infrastructure Program would be provided to the governor of each state via formula distribution. The governors, in consultation with a designated federal agency and state directors of rural development, would have discretion to choose individual investments to respond to the unique rural needs of their states.

- 20 percent of the funds under the Rural Infrastructure Program would be reserved for rural performance grants within eligible asset classes and according to specified criteria.

- Funds made available to states under this program would be distributed as block grants to be used for infrastructure projects in rural areas with populations of less than 50,000.The Rural Infrastructure Program outlines the following way of determining how rural any given state is:

Distribution of Rural Infrastructure Program Formula Funds

The statute would create a “rural formula,” calculated based on rural lane miles and rural population adjusted to reflect policy objectives. Each State would receive no less than a specified statutory minimum and no more than a specified statutory maximum of the Rural Infrastructure Program formula funds, automatically. (p.6-7)

- Funds made available to states under this program would be distributed as block grants to be used for infrastructure projects in rural areas with populations of less than 50,000.The Rural Infrastructure Program outlines the following way of determining how rural any given state is:

According to the proposal, states could also apply for the Rural Performance grants for specific projects within two years from the enactment of the infrastructure proposal. Grants would be available for up to ten years, or until the funds run dry.

Asked about his take on the private industry picking up the tab, Sen. Manchin said that, in his view, private industry is good for more urbanized areas, but that “in rural America … there’s not enough market. If somebody wants to come in and when they do, they will take the lion share and not make it any easier at all for people who live there.”

Rosser shared a similar view: “there’s no incentive unless they (private companies) are heavily subsidized.”

April Keating and others we talked to think the proposal’s language is a code for more leaniacy towards big businesses.

And that’s an important point to keep in mind. The administration’s proposal pushes for more engagement on the part of private industry by easing the permitting process, extending tax exemptions, or lessening the oversight, while at the same time arguing for benefits for the citizens and disregarding rampant environmental and health dangers.

Asked about its position on the funding related to water infrastructure in the President’s Infrastructure Initiative, an EPA official who wanted to remain unnamed admitted that the agency is not familiar with its specifics.

Although the funding itself for the initiative seems to be in question, it is worrisome that the agency that could be involved — in different capacities — with many of the projects looking to receive money from the proposal is not familiar with its details.

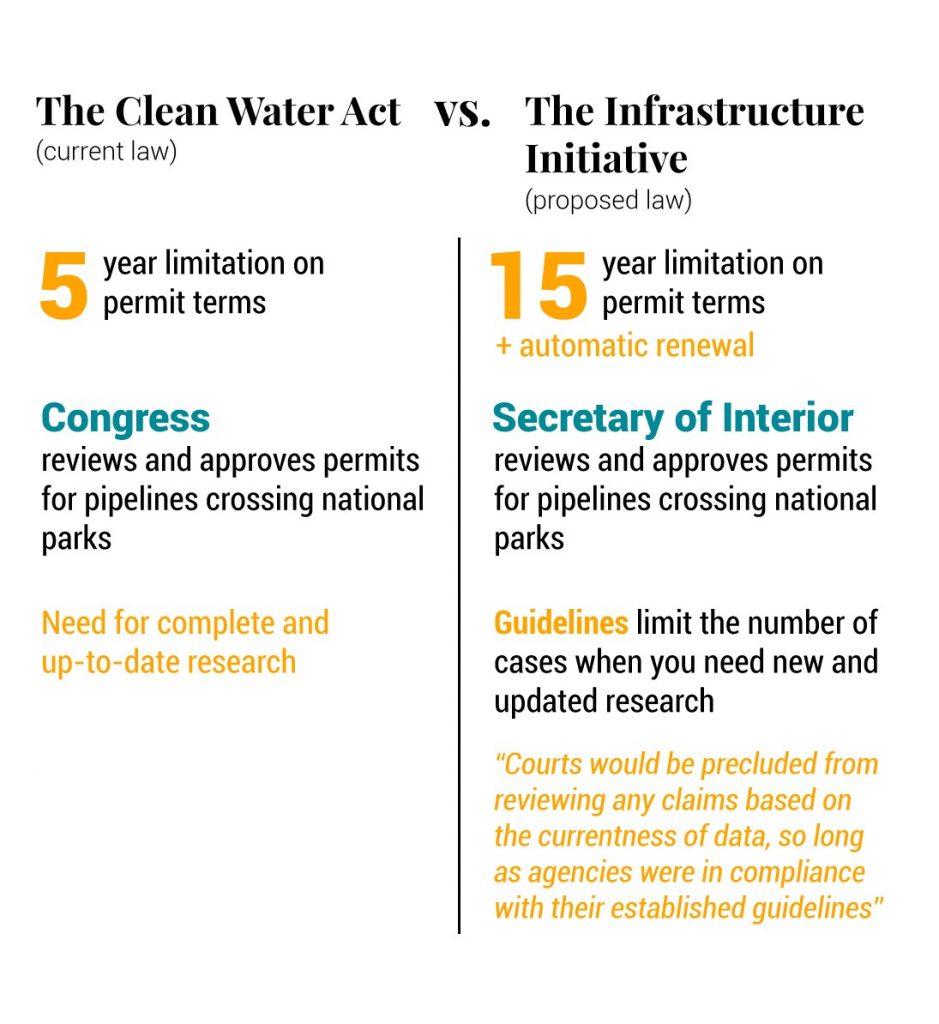

Issues involving the EPA range from extending permits’ legibility from five years under the Clean Water Act to 15 years to, in some cases, allowing for automatic renewals to providing tax incentives to invite private investments in water infrastructure such as sewage facilities, solid waste disposal facilities or in environmental remediation costs on Brownfield and Superfund sites.

While political pressures first influence the shape of laws, it’s also the political appointments at the level of the Cabinet Secretary of the Governor that lead the enforcement by West Virginia’s State Department of Environmental Protection.

Another piece of the puzzle is the failure to keep people and companies accountable.

Keating told 100 Days that the mining companies often struggle with the disposal of waste, and use methods that are controversial to say the least. “Now they’re talking about spraying it on roads. The brine itself that comes out of the earth is ten times saltier than seawater. And so even the brine without the chemicals would kill anything.”

Appalachian communities tend to show a lot of mistrust towards government regulations, just as they show mistrust to the very industries that have been the economic backbone of the region. Rosser thinks that missing trust is a big part of the problem, but the current politics don’t make it any easier for people to change their minds.

For example, on April 23 West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice issued his third executive order expediting permitting procedures for businesses, following two that rolled back and halted industry regulations. He also put a moratorium on new regulation and set up an expedited process for permit approvals for certain projects.

“Political forces and benefits to industry do get favor, sometimes over the science or what’s in public interest in terms of environmental protection and health protection,” Rosser said.

The recent “Almost Heaven” ad campaign was designed to promote tourism in West Virginia. Yet, Rosser said that “when you travel in West Virginia, water is everywhere and some pollution is invisible. It looks good. It looks pretty … We don’t know what’s in the water,” she pointed out. Ironically, a majority of the video ad showcases pristine-looking streams and creeks.

But water infrastructure investment could be a part of something much broader than providing essential services.

According to professor of geography Martina Angela Caretta of West Virginia University, “If there was a concerted effort … to put more money into restoring infrastructure, restoring rivers and really pushing this restoration economy, would actually be a big push towards transitioning of the economy of Appalachia.”

Prof. Caretta believes there is a workforce ready to take on those jobs, as well as plenty of grassroots organizing happening around the state. We will take a closer look at those individuals and organizations ready and willing to take on economic and environmental challenges.

This is the first of a two-part series. Part two of this article profiles individuals and groups across the region that focus on solving problems diagnosed here.

Writing and reporting: Jan Pytalski

Editing: Lovey Cooper, Colleen Good

Infographics: Shayla Klein

Additional reporting and videography: Emily Pelland