President Donald Trump won West Virginia by 42 percentage points in 2016. He’s holding on to high approval ratings in the state and conservatives paint Democrat incumbent U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin as vulnerable. Long known as a moderate Democrat, Manchin has been in West Virginia politics for three decades. With the seat up for grabs this year, the national spotlight has been on the GOP primary — in which hopefuls are trying to align themselves with Trump.

But this year, the Democratic stalwart in West Virginia politics faces his own primary challenger in progressive Paula Jean Swearengin — an activist-turned-candidate who says Manchin hasn’t done enough to retain the party nomination.

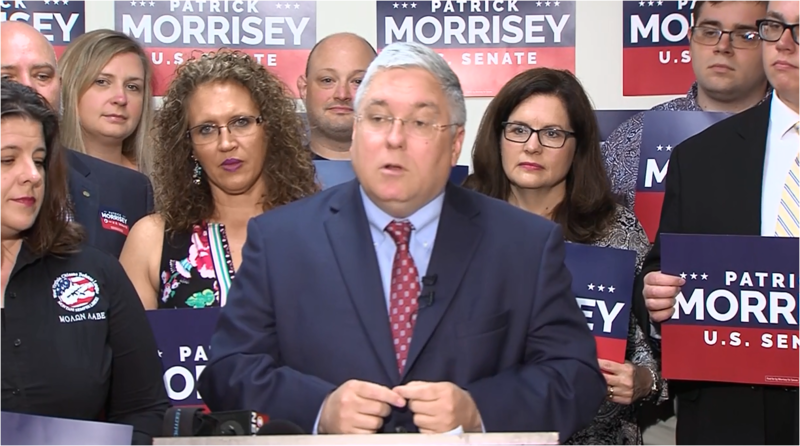

When the president visited White Sulphur Springs in early April, the stop was billed as a roundtable discussion highlighting the effects of recently passed tax-reform legislation. With GOP Senate hopefuls Evan Jenkins and Patrick Morrisey flanking Trump, the event veered toward attacks on Manchin and his no vote on the tax bill.

“The Democrats have a problem. I mean, look at your senator. He voted against. Joe — he voted against. It was bad. I thought he would be helpful,” Trump said at the event.

Overall, though, Manchin has voted with the Trump administration more than 61 percent of the time — including legislation and nominations, according to Senate records. He says he votes based on the issues themselves and what’s best for West Virginia.

“I say to the people of West Virginia you’ve hired me. I work for you. I do not work for the president but I want to work with him and I try every day and I will try,” Manchin said in a recent meeting with the media.

That record puts him at odds with the national Democratic Party. Manchin has voted against a majority of Senate Democrats 29.3 percent of the time in the 115th Congress, according to Propublica’s Represent, a web app that tallies congressional voting records. He ranks first among all senators in voting against his party — with the average Senate Democrat breaking against the majority of the party’s vote 10.1 percent of the time.

He landed in Washington after winning a special election following the death of Robert C. Byrd in 2010. Since then, Manchin has touted himself as willing to work across party lines to compromise.

“I don’t look at Republicans as my enemy, I look at them as my friends and my colleagues — and we’re all in this together. You’ve got to be able to find a pathway for it,” Manchin said. “For people to take a hard line on one side or the other — whether it’s the hard right or the hard left — you cannot get anything accomplished.”

But it’s those attempts to reach across the aisle and frequent voting with the Republican majority that is in large part what drew Manchin’s primary challenger into the race.

“He calls himself a West Virginia Democrat, but I’m not sure if he knows what that means,” said Paula Jean Swearengin, a native of Mullens, West Virginia who identifies as a coal miner’s daughter and coal miner’s granddaughter.

“The reason to take him on is because he’s not adhering to the platform of the Democratic Party and he’s not serving the working class,” she said.

After asking Manchin in person for help with the economy in southern West Virginia and to tackle environmental issues like water quality, Swearengin says she felt unheard and overlooked.

She took her pleas to U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders when the Vermont politician made a stop last spring in McDowell County for a taping of a town hall on MSNBC’s ‘All In with Chris Hayes.’

“The reason that I went to go see Bernie Sanders is because I was begging him for hope. I mean, I’ve begged for this state for years and I admired him because he was the only senator to sit down with me and talk to me like I was a human being,” Swearengin said.

Swearengin is backed by Brand New Congress, a political action committee established by former staffers and supporters of Sanders’ campaign for president in 2016. The group is aiming to run progressive, working-class candidates around the country in hopes of combatting a political environment they say is dominated by big money.

“[The intent] of this nation was to have a diverse set of people in any and all walk of governments. It wasn’t designed to have paid-for, polished politicians to represent us. This nation was built by the people for the people and of the people,” she said.

Many say Swearengin faces an uphill battle to beat Manchin for the Democratic nomination. Beyond name recognition, Manchin’s fundraising efforts have outmatched Swearengin’s by more than 30 to 1. She’s raised nearly $200,000 to Manchin’s $6 million.

Swearengin remains undeterred. Despite identifying as a coal miner’s daughter, she’s hoping to take on the industry that she says has wreaked havoc on where she grew up and still lives.

“There’s no reason as a coal miner’s daughter that I should have to beg for something so basic as a clean glass of water. At the same time, we see coal miners that want to just feed their families. And we’ve heard that propaganda tree hugger versus coal miner. It’s even been labeled environmentalist before and that’s not it,” Swearengin explained.

“We we want it all. There’s no reason that we can’t have basic human rights and, like I said, we don’t even have adequate sewage systems,” she added.

After teachers across West Virginia went on a nine-day strike calling for better pay and benefits, many observers of state politics have wondered if the labor movement — one that caught fire in other deeply red states — can translate to a wave of wins for progressives.

But as May 8 nears, Manchin’s campaign is focused more so on November and his potential challenger in the midterm election.

“My approach is this: I don’t pick my opponents. They picked to run and choose to run against me. And whoever that may be, we’ll put our records up hopefully and try to get the facts out — as hard as it is in today’s toxic atmosphere,” Manchin said.

Unlike the race for the GOP nomination for U.S. Senate, state Democrats did not arrange debates between Manchin and Swearengin. West Virginia Democratic Party chairwoman Belinda Biafore said no media outlet ever contacted the organization to organize a statewide debate.

This article was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.