This story was originally published on Scalawag on December 15, 2016.

Since we first published this story in 2016, Alabama instated a new law defining crimes of moral turpitude and eliminating the ambiguity that led to thousands of potential voters being disenfranchised. Pastor Kenneth Glasgow’s organizing over the years, and his advocacy for this law in particular, played a big role in this important change.

Scalawag has learned that last week, Glasgow was arrested and charged with capital murder in a shooting death in Dothan, Alabama. Aware of the ways that progressive organizers have been targeted in the past, many people who have worked with Glasgow––including community leaders, clergy, lawyers, and activists––are now rallying to his defense. We will follow this situation as it develops.

When there’s a lizard in church, someone has to catch it, and on a Saturday in February in Dothan, Ala., that someone was Pastor Kenneth Glasgow. He had barely finished an impassioned call to action––one of many he would make that day — at a meeting of Black community leaders, when he noticed the lizard scuttling across the sanctuary’s deep-red carpet. He set off chasing it, whizzing around the room’s perimeter as the next speaker took his place. This image would return to me throughout the day, as with each passing hour I became certain of one thing: the man does not stop moving. Glasgow is in perpetual, purposeful motion, and his purpose — when it isn’t lizard catching — is restoring, and enforcing, the voting rights of formerly incarcerated people.

“There are 272,000 people in Alabama disenfranchised by felony convictions,” he told the crowd in the squat, concrete church on a grassy corner lot.

“Y’all gotta help me get this word out. Felons can vote,” he preached.

If those messages sound contradictory, it’s because there are two realities in Alabama: the law on paper, and the law in practice. On paper, Alabama is one of three states in the nation where some people with felony convictions are allowed to cast ballots in prison. The other two states are Maine and Vermont, which disenfranchise no one. People with felony convictions who are eligible to vote from prison in Alabama are supposed to be able to vote once they are out of prison too. But in practice, it’s common for election officials to deny registration to formerly incarcerated felons who are eligible to vote. And prison officials have created obstacles to registering voters behind bars.

“What I found out was that it was a big problem across the state.They weren’t enforcing this,” Glasgow said as we left the church meeting and headed to his next stop––an elementary school where parents were convening.

In a red state with just over three million registered voters, upwards of 260,000 potential voters who likely lean Democratic is hardly insignificant — it’s enough to lend an eight percent boost. An August poll by the website fivethirtyeight.com showed Donald Trump ahead of Hilary Clinton by only six percentage points in Alabama. Still, the site forecasted a 97 percent chance that Trump will win the state, based on factors that might or might not be impacted by a hypothetical flood of re-enfranchised voters.

Glasgow thinks Democratic presidential candidates should pay attention to felon voting rights in Alabama: “If we got close to 100,000 people who could vote, it could sho nuff turn it from red to pink.” But it’s the local races, he says — judges, sheriffs, county commissioners, and district attorneys — where formerly incarcerated voters can make an immediate impact toward building power in marginalized communities. These races, after all, typically have low turnout yet produce some of the most personally tangible consequences.

Glasgow’s Toyota SUV, aside from providing transportation, serves as his closet, office, and pantry. Two neckties hung from the rearview mirror. The dashboard was cluttered with piles of paper. Bulk boxes of packaged snacks were stacked in the backseat. Glasgow practically lives out of his car. He regularly zooms from local speaking engagements to lobbying at the Capitol in Montgomery to registering voters across the state to feeding dozens of hungry people at a soup kitchen he founded in The Bottom — the struggling Dothan neighborhood that he grew up in and still calls home. As we drove to the meeting at the school, Glasgow told me about his origins.

He was born in Brooklyn to Al Sharpton’s father and step-sister, a complicated family dynamic that eventually led his mother to break off from the Sharptons and return to her hometown, Dothan. Glasgow was thirteen when he landed in the Bottom. “It was poverty stricken, and drugs was prevalent everywhere,” he said. “The first time I got in trouble, I told a White dude where to get drugs and he turned out to be a narcotics agent.”

That incident proved to be the starting point in a long trajectory of heavy drug use and its attendant criminal activites. In the late ‘80s, Glasgow landed in prison on drug possession and a litany of other charges. It was in prison that he met his mentor, Samuel Warrick, a politically minded minister who preached the importance of civic and community engagement. “I had an epiphany from God to start The Ordinary People Society,” Glasgow explained.

Together, Glasgow and Warrick founded TOPS in 1999 with a mission to provide care to people who “suffer the effects of drug addiction, mass-incarceration, homelessness, poverty unemployment, hunger and illness.” Glasgow says there are now 22 TOPS chapters across the country, mostly concentrated in the South.

When Glasgow got out of prison in 2001, he started ministering in jails and registering the inmates to vote. He began the work of getting his own voting rights restored— a process that would take several years. At the same time, he started a tent revival in The Bottom. He would set up a big, white tent in a vacant lot and preach there for three weeks— the city’s limit on the time a temporary structure can be erected. He would dismantle the tent and leave it down for a few days, then put it up for another three weeks.

People in the neighborhood gravitated to his gritty style, although he was confronted once about his use of cuss words. “They said, ‘You’re a preacher, you can’t be cussin.’ Well, God didn’t make me that way. I’m from the street,” Glasgow explained.

Many folks who came to his tent revivals were also formerly incarcerated. As Glasgow navigated the system to restore his own voting rights, he simultaneously began guiding others through it. Glasgow completed the restoration process and regained his right to vote in 2004. Then he found out he had never actually lost it.

It was 2007, in a meeting of Republican lawmakers. Glasgow was demanding that the attorney general at the time, Troy King, do more to aid in felon voter restoration. Glasgow remembers an exasperated King saying, “Next you’ll be talking about moral turpitude!”

Moral turpitude? Glasgow had never heard the term. A lawyer referred him to Section 177 of the Alabama Constitution, which states: “No person convicted of a felony involving moral turpitude, or who is mentally incompetent, shall be qualified to vote until restoration of civil and political rights or removal of disability.”

In other words, if your felony doesn’t involve moral turpitude, you remain qualified to vote. Now, moral turpitude has meant different things at different times, and the concept is still murky. But upon further inquiry, Glasgow learned that drug possession, the charge that landed him in prison, did not constitute moral turpitude. And a whole host of other felonies didn’t fit the moral turpitude category either. Yet it was a commonly held belief in Alabama — among felons and election registrars alike — that all felons lose their right to vote and only regain it by completing the restoration process. Moral turpitude was a revelation.

“It opened the door for a voting block that never existed,” Glasgow said.

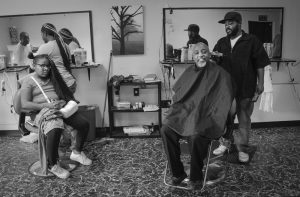

After Glasgow’s presentation at the elementary school, we headed to The Bottom, pulling up outside an old, two-story brick building that housed mostly empty storefronts on an otherwise residential street. A door at the corner of the building was open, and a young man was posted there like a bouncer at a club. Glasgow greeted him as we went inside, where two barber’s chairs sat in a sparsely furnished room that was dark and cool. Kenneth Glasgow Jr., who goes by Kenny, was shaving a man’s head. Next to him, a woman braided a young girl’s hair. When Glasgow Jr. was done with his customer, his father took the chair.

“If I have to pay taxes, I should be able to vote,” Glasgow Jr. told me as he trimmed the elder Glasgow’s hair.

At 28, Glasgow Jr. completed ten years of probation for armed robbery. Now, three years later, the soft-spoken father of four is still struggling to get back on his feet. He can’t find steady work, as most employers reject him on the basis of his criminal background. And he hasn’t been able to access federal assistance programs to fill in the gaps where his under-the-table income falls short; until recently, Alabama banned felons from qualifying for public housing, food stamps, and other public assistance programs. (The elder Glasgow was instrumental in changing that law.)

Glasgow Jr. has little recourse to try to change the policies that are hurting him. According to a 2005 opinion by the Alabama attorney general, armed robbery is a crime involving moral turpitude. So Glasgow Jr. must complete the restoration process before he can vote. But that will take years. Under Alabama law, restoration isn’t complete until you finish your sentence and pay all fines and court fees (the American Civil Liberties Union likens this rule to a poll tax). Glasgow Jr. was not only sentenced to 10 years probation, he was also slapped with a $22,000 fine. He is currently paying it off in monthly installments of $120.

“And if I don’t pay it, I go back to prison,” he explained.

Glasgow Jr. would like to try to get a full pardon, which would enable him to vote and clear his record. But that can cost money too, more than he has.

“If you’re broke, you get treated like trash,” he said.

Glasgow next shuttled me to an aging strip mall painted Easter-egg blue, which he calls ‘The Plaza.’ There, he has been gradually building a “one-stop shop” for community empowerment. There was a youth space where he has held summer camps and after-school programs. Offices and an assembly hall provided space for job training and anger management classes. Next door to the assembly hall was a barber shop run by a man who graduated from a program Glasgow created called Prodigal Child, in which he mentors and houses people recently released from prison. Then there were units full of furniture and supplies for projects still in the works. Within several months two of these — a restaurant that exclusively hires formerly incarcerated people and a community radio station — would be up and running. A print shop for producing community-driven publications is still in development.

In the middle of the tour, Glasgow got a phone call, and his tone turned urgent. “It’s Kenny,” he said. “They arrested him.”

We sped back to The Bottom and found Glasgow Jr. handcuffed in the back of a police car. Glasgow talked with the officer and learned that he had a warrant on his son for “failure to comply.” Glasgow Jr. had missed a court-mandated drug class.

“The drug classes have been around for a while but they really became a permanent fixture over the past four or five years,” Glasgow told me when we were back on the road. He said that a growing number of people in Dothan are being sentenced to the classes, which cost $40 or $50 and are all run by the same company, Spectra Care.

As we rolled through The Bottom, Glasgow would honk, or wave, or holler when we passed people he knew. Which is to say, everyone we passed. Glasgow would offer up snippets of their stories— that person had their voter registration application turned down three times. There’s someone who lives in the halfway house he founded for formerly incarcerated men. Those folks are having a fish fry to raise money for a new community program.

The Bottom began to look like a web, with everyone connected by dozens of threads that all ran through the courts and the jails and the prisons one way or another. The threads also ran through spaces of survival and care that this overarching net of policing necessitated: the church, the soup kitchen, the barber shop, The Plaza, the fish fry. In this nearly all-Black, all-poor neighborhood, the criminal justice system had an entrenched presence — a visceral but invisible chokehold not unlike the one that killed Eric Garner in New York City in 2014 and birthed the Black Lives Matter rallying cry, “I can’t breath.”

This chokehold isn’t new, and it isn’t an accident. It is, in part, the legacy of a group of self-proclaimed White supremacists who gathered at the turn of the last century to re-write the Alabama state constitution.

“And what is it that we want to do?” asked John B. Knox, president of the 1901 Alabama Constitutional Convention, in his opening address to convention delegates. “Why it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish White supremacy in this state.”

Knox and the 155 delegates who convened at the capitol in Montgomery declaimed that the rise of Black people to elected office, “by force of Federal bayonets,” after the Civil War had wreaked havoc on state governance. The goal of the Alabama Constitutional Convention, like others held in states throughout the South around the same time, was to re-establish electoral power of Whites by devising legal ways to keep Black people from voting.

During the Alabama Convention, which is documented in a series of daily journals available online, Knox and his peers discussed methods other states had used, like poll taxes and literacy tests. But much of the debate focused on the potential to disenfranchise huge numbers of Black voters based on a tailored list of crimes some delegates believed were commonly committed by Black people. Under the state’s 1875 constitution, felons were already disenfranchised. The new constitution vastly expanded that to include twenty-nine specific crimes that ranged from the serious— murder— to minor offenses like vagrancy. But it was another addition that would prove most potent: the new constitution disqualified from voting anyone who committed a crime involving “moral turpitude.” Left undefined, the vagueness of the term opened the door for nearly any crime to be stamped with the label, a flexibility that enabled registrars to disqualify vast numbers of Black voters.

“They kind of decided on the fly what was moral turpitude,” Birmingham lawyer Edward Still said in a phone interview. Still, whose career has focused on voting rights and electoral laws, was referring not only to registrars, but judges and attorneys general too.

In 1916, the Alabama Supreme Court defined moral turpitude as, “an act that is immoral in itself regardless of the fact of whether it is punishable by law,” a definition hardly clearer than the term itself.

“Generally accepted principles among most Christians,” is how Still described it, although he was quick to acknowledge that plenty of crimes which make no appearance in the Ten Commandments have been mantled with moral turpitude.

In 1985, Still tried the only case to successfully challenge Alabama’s disenfranchisement law which, at that time, was in section 182 of the state constitution.

In Hunter v. Underwood, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Court of Appeals ruling which found that the law had an indisputable discriminatory impact. The Court of Appeals ruling stated that, “By January 1903, section 182 had disfranchised approximately ten times as many Blacks as Whites. This disparate effect persists today. In Jefferson and Montgomery Counties Blacks are by even the most modest estimates at least 1.7 times as likely as Whites to suffer disfranchisement under section 182 for the commission of [misdemeanor] offenses.”

In the Appeals Court, historians took the stand to testify that the law not only had discriminatory impact, but discriminatory intent as well. “The Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901 was part of a movement that swept the post-Reconstruction South to disenfranchise Blacks,” the judge’s opinion read. “The delegates to the all-White convention were not secretive about their purpose.”

The plaintiffs in the case were a man and a woman convicted of a misdemeanor crime that was included in the long list that convention delegates crafted in 1901. So the 1985 ruling only restored voting rights to misdemeanants — but not those with felony convictions. Whether the same grounds could be used to restore voting rights to felons wasn’t a question Still was able to grapple with in the 1980s.

“We were taking one step at a time,” he said.

Then, in 1996, state lawmakers revised the constitution, and the contents of Section 182 were condensed and changed into Section 177. The provision came as a revelation to Glasgow over a decade later: “No person convicted of a felony involving moral turpitude, or who is mentally incompetent, shall be qualified to vote until restoration of civil and political rights or removal of disability,” it read.

Now no one with a misdemeanor conviction can be legally disenfranchised, and the only felons who can be are those whose crimes fall under the banner of moral turpitude. Those crimes were finally spelled out in an attorney general’s opinion in 2005, but the list was admittedly incomplete and functioned more as a memo to staff than a legally binding document. Glasgow found that hundreds of thousands of people with felony convictions have been disenfranchised — through lack of information and illegal disqualification — since the law was changed in 1996.

After Glasgow learned that not all Alabama felons are disenfranchised, he met with officials from the Alabama Department of Correction. It was late July 2008, just a few months away from the presidential election that would deliver the nation’s first Black president to the White House. Glasgow presented a plan to register eligible voters in prisons across the state to vote by absentee ballot. On Sept. 5, ADOC’s Commissioner at the time, Richard Allen, approved the plan.

Glasgow identified 6,000 inmates who were incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses, which do not fall under moral turpitude. In less than two weeks, he held his first prison voter registration drive at Limestone Correctional Facility near Huntsville. The very next day, he registered voters in the Birmingham Work Release Center, and two days after that, he took his crusade to the Mobile Work Release Center. That’s as far as he got.

“Republicans had a conniption. Racism stood out like racism never stood out before,” Glasgow told me.

An Associated Press journalist had accompanied Glasgow to the Birmingham Work Release Center and reported that 80 inmates had registered to vote. The chair of the Alabama Republican Party, Mike Hubbard, did not like the news. He wrote a letter to Allen stating that the Party was against, “the registering of individuals, who have committed crimes and are currently incarcerated in the penal system.” The same day, Allen banned Glasgow from registering any more prison inmates. (Ironically, Hubbard is now serving four years in prison for 12 felony ethics violations, which are not considered crimes of moral turpitude. Thanks to Glasgow’s efforts to illuminate the moral turpitude disctinction, Hubbard will still be able to vote.)

Glasgow turned around and filed a lawsuit with the assistance of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The lawsuit was settled in Glasgow’s favor just three days before the state’s deadline to register for the Nov. 4 election.

“We went through every clink, glitch, snare and prevention tactic,” Glasgow told me. He explained that once the lawsuit was settled, Republican lawmakers tried to pass a bill defining moral turpitude. On the one hand, it would have brought much-needed clarity, but on the other, it would have greatly expanded the list of crimes thought to fall under moral turpitude. Notably, the bill named marijuana possession in the first degree, which up to that point had never been considered a crime of moral turpitude.

Glasgow fought that bill, and his lobbying helped defeat it. Since then, he’s maintained a regular presence at the state capitol, where he has contributed to significant victories for Alabama’s formerly and currently incarcerated community, including parole board reforms, a law that sends parolees who fail drug tests to treatment instead of prison, and changes to the state’s drug classification laws, to name a few. At the same time, he has registered thousands of inmates to vote in jails and prisons across the state.

Back in The Bottom, we made our way to Mama Tina’s Mission House, the soup kitchen named for Glasgow’s mother, where TOPS serves lunch and dinner five days a week. Tina Glasgow lives around the corner, in the same home where she raised her son. He now lives in the house next door on one side and runs a halfway house for men transitioning out of prison on the other. When I met Tina Glasgow at her home, she told me that years ago, when Glasgow was addicted to crack, cooking for him was a form of harm reduction.

“I would always leave food on the stove. Wasn’t nobody at home during the day, so he would bring crack buddies to the house and they would mess around. If there was food, they would usually eat it and just fall asleep instead of going out and robbing somebody’s house,” she explained.

“When he got home [from prison], he wanted a soup kitchen, to do harm reduction. And he thought it fitting to name it after me.”

By the time we arrived at the soup kitchen, it was late afternoon, and even after two speaking engagements, a few quick meetings, shuttling a reporter around, and dealing with his son’s arrest, Glasgow’s work was not finished. It was time for a voter registration drive — Bottom style.

A few people were waiting for us at picnic tables outside of the soup kitchen bungalow — three young guys and an effusive woman who introduced herself as Bright. One of the men had just gotten out of prison and wanted to register to vote. As he filled out the forms, a couple rolled up with three young children in a stroller and an older kid trailing along. The whole crew mingled for a while, eating snacks from Glasgow’s backseat pantry and cracking jokes while the kids played. Gradually, the crew gained steam — for what, I wasn’t yet sure. But when Glasgow gave the word, we all set off walking down the street.

It being a Saturday, everyone was out. On porches, steps, sidewalks, in cars with windows down and music cranked up.

“Are you registered to vote? You got a felony? You can still vote!” Bright shouted as we approached. Residents of The Bottom came out of their homes, slowed their cars, and paused from barbecuing to register. At each stop, Glasgow traded information — his latest news from the Capitol, the prisons, the D.A.’s office, for their updates on relatives who were incarcerated or on their own struggles to access services, shake off court fees, and secure voter registration.

We ended at a backyard party where several generations of a family were gathered to celebrate a birthday.

“Don’t ask her about it,” Glasgow whispered to me as we joined the throng, “but there’s a lady here whose son was killed by the police in Eufala last month.” Three weeks later, Glasgow would lead a group of folk to blockade the main highway that runs through Eufala, a town north of Dothan, in protest of the killing.

Glasgow circulated through the crowd, alternating between shooting the shit and talking seriously. A middle-aged guy with a green drink in a plastic cup told Glasgow he had been out of prison for 15 years and, “Still they’re telling me I can’t vote. All I had was possession.” Another man chimed in that he had registered successfully but hadn’t received his card after many months; he asked Glasgow to check on it for him. A younger guy bluntly stated, “I don’t vote and here’s why: my vote doesn’t count.”

As they talked, a police car crept down the alley between the yard and the house next door. Everyone’s eyes followed it until it turned the corner. Later, the police returned, and this time confronted the party host to say that the music was too loud.

Spend a day with the Pastor Kenneth Glasgow, and it becomes clear that, in communities like The Bottom —where poverty, police violence, and the carceral state loom large — voting is about more than casting a ballot for candidates that, as Glasgow doesn’t hesitate to say, are too often the lesser of various “evils.”

In some ways, the act itself is empowering, as Tina Glasgow explained when we visited: “We as laymen asking people to vote, rather than politicians asking them to vote, we get more people to vote that way. They feel important and it wasn’t that way before.”

But the outcomes are very real too, and not only in the ways that you’d expect.

“Prisons are mostly located in rural White areas. They count prisoners in the census and get more federal dollars that way,” Pastor Glasgow told me. “But in prison you vote your absentee ballot from the county you came from, and then that’s where you’re counted for the census.” In other words, voting from prison can potentially restore federal resources to Black communities that have seen wealth diverted to White areas where their family members are locked up.

Then there’s the fact that, according to a 2012 report by The Sentencing Project, 5.85 million people nationwide are disenfranchised from voting because of felony convictions and laws against voting while incarcerated. The majority are concentrated in six Southern states, including Alabama. That’s more than enough to shift electoral politics in a big way — especially in high-disenfranchisement states like Georgia (275,866 disenfranchised voters) with a narrower margin between Democratic and Republican presidential candidates (Trump was in the lead by only three percentage points as of August.)

“It’s a sleeping giant,” Glasgow said. He has expanded his work to other states, connecting with local organizations to change felon voting laws and state policies across the nation.

There is something deeply visceral going on as well, something about the constant police presence in The Bottom, the fear that everyone lives under, for their own safety and that of their loved ones. That chokehold didn’t begin in 1901, but it acquired a new purpose that year. With moral turpitude, the chokehold became a tool to keep Black folks out of government, out of political power. Today, the zeal for voting amongst residents in The Bottom seems less about the candidates, and more about reverse engineering an equation that, thus far, has worked against them: defeat moral turpitude, gain some measure of political power, and they might throw off the chokehold.

As dusk fell, Glasgow and I sat in his SUV in the parking lot of the Dothan County Jail. For the first time he sounded tired, as he contemplated the long legacy of moral turpitude in Alabama.

“I often wonder, how do I approach [lawmakers] to give some kind of recompense or reparation or restitution for all those years of lost voting rights,” he sighed.

After a pause he said, “The biggest thing is getting the information out to people that they can vote.” And he headed inside with a stack of voter registration forms.

This story was originally published on Scalawag.