Young people in protected rural areas in Brazil see positive things in both contemporary and traditional lifestyles. What if choosing one didn’t preclude holding on to the other?

Prosperity manifests differently for different people. In the United States, some might say living well requires wealth. In the Brazilian Amazon, some think prosperity means staying in the forest, but in a 21st century way.

In 2017 I spent a year as Fulbright Research Fellow with the Intsituto Socioambiental, a Brazilian nongovernmental organization that supports communities living in forests and protected areas. The Amazon rainforest is a rural region dramatically different from most rural areas in the United States: a wild frontier with violent land grabbing, uncontacted indigenous peoples, and a multitude of indigenous territories and protected areas. At the same time, many of the larger questions that are familiar to American rural communities also have their analogs in the Amazon – the biggest, perhaps, is about young people: deciding whether to stay or go.

+++

During the Amazonian dry season, the unrelenting summer sun dries up the little Riozinho do Anfrizio, leaving only a boulder filled, muddy creek. A week’s low-water sojourn up that river, hiding from the heat of a midday sun, I found myself discussing what young people from the most rural place in the Americas thought about staying rural – what they thought prosperity might mean for the generation of young people growing up in this part of the Amazon rainforest.

Off the Xingu River in the eastern Amazon, the Riozinho flows through a mosaic of protected areas called the Terra do Meio – the Land in the Middle – between the Xingu and Iriri Rivers. It is 8,500 hectares of forests (roughly the size of Delaware) filled with indigenous territories, national parks, and sustainable-use areas called “extractive reserves,” or reservas extrativistas. In total, the region has perhaps 2,000 families, scattered across villages and homesteads.

The Riozinho is the little artery of one of the three reserves in the Terra do Meio. It’s where boats and motorized canoes ferry people, merchandise, gasoline and diesel up the 50 some miles of inhabited riverbank.

When raining, it might take a day’s motor-boat ride to get to the Morro do Anfrizio from the city – Altamira, an Amazon frontier boom town, which started explosive growth in the 1970s with the arrival of the Transamazon highway. In the dry season, as it was now, the trip to the community center on the Riozinho becomes a bigger journey: a day in a pick-up driving from Altamira to a river port off an illegal (although locally sanctioned) highway cutting across indigenous territory belonging to the Arara people. Then two days on a motorboat, unloading the 25-foot aluminum craft and dragging it up rapids and little waterfalls, to reach the mouth of the Riozinho. Leave the motorboat, and take another two days travel up the Riozinho in a wooden canoe with an outboard motor, and one reaches the Morro do Anfrizio.

At the Morro, one finds a health post, some houses for visitors to stay, an airstrip for medical evacuation, a school, and three schoolteachers. Few families of riberinhos – river communities that trace their roots to early 20th-century rubber tapping economies – live at the Morro. There are few gardens – the forest farms that provide an abundance of manioc flour, a high caloric starch and local staple, fruits and some vegetables. The riberinhos build their homesteads in familial clusters, at some distance to the hub, upriver and downriver, the children traveling several miles a day by boat and foot to arrive at school.

After 10 years of NGO and government investment in the Morro, this little base is the oldest and most built out community hub in the Terra do Meio’s three Extractive Reserves. The Riozinho do Anfrizio is a place where, 15 years ago, malaria was a plague, hepatitis common, where many people had lived entire lives and never seen a grouping of houses bigger than the old rubber boss’s camp of a dozen structures, least of all the city less than 100 miles downriver. In a decade and a half, so much changed.

Youth

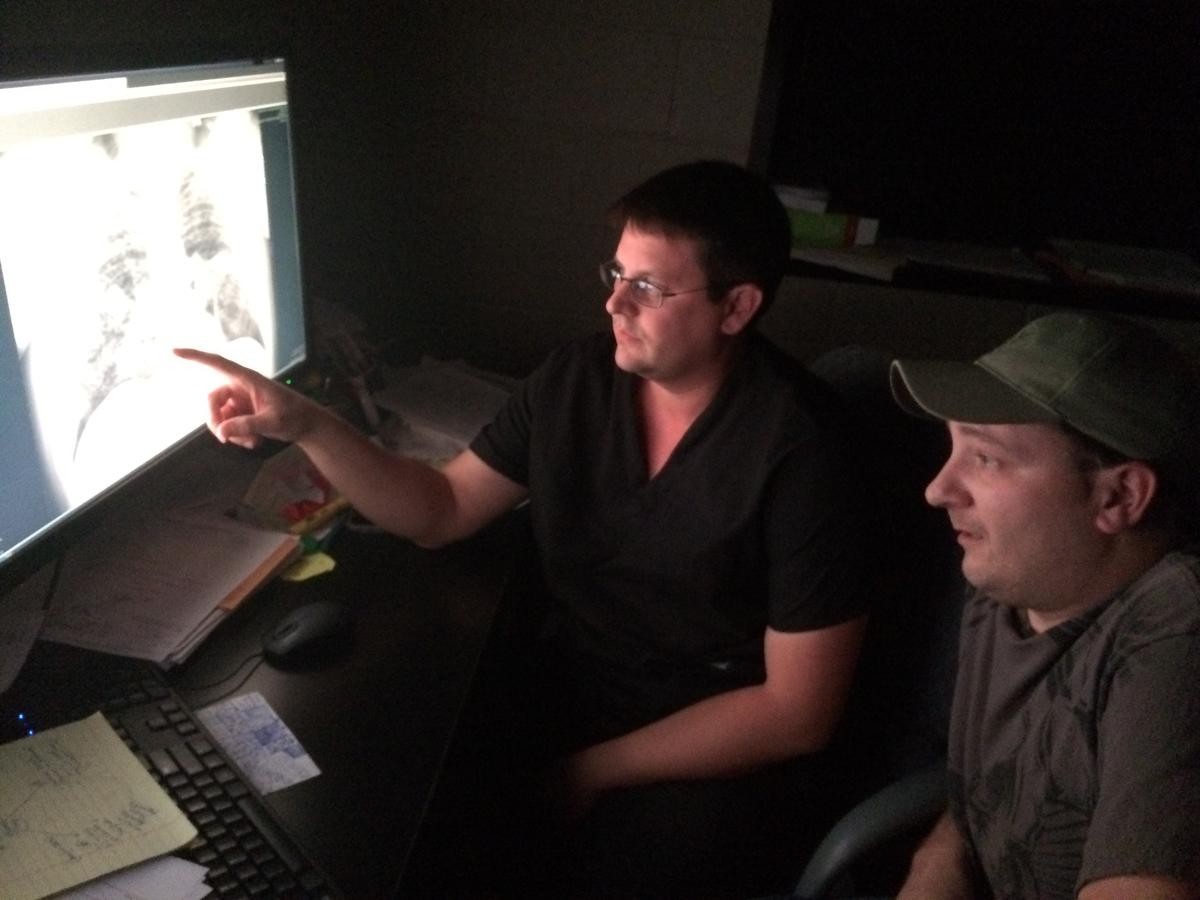

For most young people, the question of what they want in life is a provocative question. For those young people of the Terra do Meio Extractive Reserves, the question is fraught, filled with questions of the future of the parks and the forest. That was the question we found ourselves discussing on a late October day on the little Riozinho. I sat with Herculano Oliveira Filho, or Loro, as he’s known, and Romário dos Santos, hiding from the heat of the oppressive midday sun, discussing life, their futures, and a collaborative research project.

Loro, nearly 30 years old, was born on the Riozinho. As Loro explained, he has seen the world turn upside down in his lifetime. The world those on the river were born into involved paddling a canoe for a day, or two or three, to get to a neighbors’ home for a Christmas or Easter celebration. They fished and hunted, farmed, and lived in what Loro calls, “an unrecognized relationship to the state.” The nearest doctor was downriver two days’ paddle in the indigenous territory. Going to town was a rare feat , involving hitching rides with the few boat peddlers that passed by when the water was high enough, buying non-timber forest and agricultural products, selling city goods, such as sugar, tobacco, fishing hooks, shotgun shells and alcohol. But his life has changed dramatically: that started when he was 17 years old and the area was federally declared a reserve. The military occupied the river, cleared out land-grabbers and loggers, and the battalion’s sergeant established a school where Loro learned to read.

To Prosper

On that bright, breezeless October afternoon, we sat underneath a shady pavilion, and talked about how to define the “good life” – what they wanted to happen to the region, but more, to themselves.

Loro was clear: as someone who had been in territorial government and had opportunity to travel to conferences – to Brasilia and São Paulo – who watched the nightly news when the generator was on, and spent at least several months a year in the small frontier city, he has a certain drive to gain access to a culture and a level of connectivity that many on the river might not.

I don’t want money. Money isn’t important, except as a way to get what we need. I don’t believe it brings happiness. And I don’t want to live in the city, because to live there you need so much money. I want a garden, here in the Reserva – I want to be able to eat as much fish as I pull out of the river, and feed myself, and my family. But I also want enough money to go to town whenever I need, and buy what I need. The necessities. I want to have a nice house: cement floors and a tile roof, and enough solar panels to run electricity at night. I want Internet to be in touch with what happens in the world, and know more. And I want enough to have a computer and a camera and a cell phone. That technology is important. And I want to be able to travel, once a year – to leave here and go somewhere else.

Later, Loro would tell me that he wanted to open a small bodega – to run a real grocery store, by the river’s standards – to ensure that he and the rest of folks never ran out of the basic necessities when the river was low. These things that they all loved and hated to live without: coffee, sugar, cooking gas, toilet paper, little cookie treats, and so on.

But the younger Romário had a different perspective. At 22, not having left his parents’ home yet, he gave a simple response: “I don’t know.”

At first, I thought this was shyness. On reflection, I think the answer was quite genuine – an answer to a tumultuous time in one’s life and in the place’s future. He also said, then and often publicly, that he never wanted to leave life on the river and in the forest.

Romário was one who took to the woods with brothers and friends for weeks, if not a month, to search for the valuable copaiba oil – a lucrative endeavor, one that could produce several thousand Brazilian dollars (Reais) (a sizeable part of a yearly minimum income), if one was diligent and lucky.

But, the question of staying rural in an Amazonian park is complicated. As Loro has said well: “We know that where there are indigenous people and riberinhos there are forests.” Which is to say, where traditional communities do not occupy the forest, ranchers and loggers do – legally or otherwise. So, Brazilian and international conservation groups have a vested interest in keeping those traditional communities in the forest.

For Romário, never leaving the forest was perhaps easier to say than do. A strapping and charismatic young man, he had fallen in love with a schoolteacher who lived in town. He enjoyed spending months in the town, using his cellphone to stay in touch with friends and connect with a broader world.

Yet Romário would be the first to tell you – what would he do in the city? Work for minimum wage as a construction worker? But he had yet never seen the urban metropoles of Brazil. He did intend to go there, to see the world. But a life in the forest, had, as he put it, “everything provided for.” One can build a house from the forest. One can plant a garden. Fish abound. Wild pork abounds. Family is strong. Soccer games bring young people together. But, the same life of his father and mother were not the life he sought, he had told me earlier. He had dreams, for the region and for himself. Perhaps he just was not sure what they were.

Romário is caught between two worlds, as I saw it. One is a world that some might look upon as a piece of the past – a life of peasant subsistence in the forest – planting gardens, hunting, fishing, and collecting the riches of the forest for petty cash, be it non-timber forest products like Brazil nuts or tree oils, or gold, or the illegally felled logs of auburn hued tropical hardwoods. The other is an urban Brazilian world filled with the dark realities of Brazil’s stark economic inequality and unbridled urbanization, yet with the illusive draws of consumer society. And, this other world also holds a certain ‘Brazilian dream,’ one that may feel more familiar to a US audience than peasant agriculture – a world of working hard, pursuing wealth, buying a house, living with internet, sending children to college.

A Rural Crisis

The crisis the young people lived with, as I understood it from talking with these young men and others, was not simply about living in the liminal space between worlds – balancing the risky allures of a city life, only to lose the security that some Brazilians look down on as peasant subsistence, but others see as a certain freedom.

Instead, I believe the youth of the Terra do Meio might face something quite like the many young people in rural parts of our globalizing world.

Cities in our modern world have served as refuges from the ravages of economic disasters, where people go when the bottom falls out of rural economies like farming or mining. They also have been home to the multitudes fleeing violent regimes like Jim Crow in the American South or conflicts and tragedy like war in Syria today or in Vietnam in the recent past. Cities also offer places of great creativity, bastions of great wealth and thus possibility for not only difference, but cultural rupture and maybe revolution. And despite non-profits and social movements focusing on keeping rural people in rural places, many young people will, for those reasons, always flock to cities.

Rural places have also offered, and offer, a different revolutionary potential – a markedly distinct way for peoples to live differently – a different kind of refuge for diversity (one only needs to look at the Brazilian Amazon and the myriad of livelihoods in indigenous and other forest communities for an example). Rural areas can enable certain stabilities and lives lived outside of the demands (and risks) of a system where everything is bought and sold. In rural spaces — in the U.S. or the Amazon – housing can be cheap, or shared by families, and connected to their ancestors who lived there before them. People can produce from the land, and sometimes still achieve the ability to feed themselves, find their own water, and sometimes even live well without wealth.

Which is to say, the youth of the Riozinho do Anfrizio, face the choice of leaving home. It’s a place that has been poor by classic economic standards, impoverished since colonization in the 20th century. But it’s a place they might love, rather than starting anew in a city as just another kid looking to make good. But both choices are valid. The question, from my perspective, may not be how to keep rural young people from the Terra do Meio in the forest, but perhaps how to give them a real choice.

What Loro articulated was a profound demand: couldn’t these young people have, and maybe deserve to have, the benefits of an urban experience – the connection, education, and access to markets – but live in the place and community they come from? Why can’t they prosper at home?

This article was originally published on the Daily Yonder.