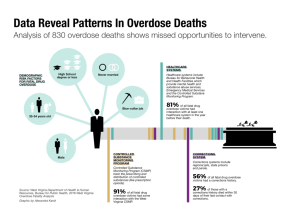

The Ohio Valley’s numbers on the opioid crisis are grim, especially so in West Virginia, which has the nation’s highest rate of overdose deaths.

But those numbers could give health workers the ability to identify people at risk of drug overdose and then reach them before they die.

That’s what researchers from the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources were hoping for when they built a data profile from statistics on the 830 residents who fatally overdosed in 2016.

Bureau for Public Health Commissioner Dr. Rahul Gupta is one of the leaders in the state facing the worst of the addiction crisis. I recently sat down with him to discuss what he has learned from the overdose data, and how the information can help reach others before it’s too late.

Social Autopsy

RAHUL GUPTA: If you have heart disease or you may be at risk of having heart disease there are a lot of risk factors. The doctor might often say you’re a walking heart attack about to happen and we need to do a set of things to lower your risk for that event.

Similar to that we looked at the hundreds of West Virginians that were dying of opioid overdose year after year. We began to think ‘How much do we really know about the risk for someone having an opioid overdose fatal or nonfatal?’ We started to look at literature and there are some known risk factors. But there’s not enough to actually understand the epidemiology of the disease itself.

We have the data. We have well over 800 West Virginians that died in 2016. Rather than just continue to count numbers, let’s start to understand those lives that have been lost. And understand what we can we learn from those human beings and what were the specific factors that made them more susceptible to fatal overdoses.

That’s what gave birth to the idea of doing this, what we call a “social autopsy” of the deaths that happened among West Virginians in 2016.

——— LISTEN ———

AARON PAYNE: And within that social autopsy what were some of the factors or categories that you were most interested in looking at?

GUPTA: We wanted to really look at beyond just a death certificate or information within the medical examiner’s office.

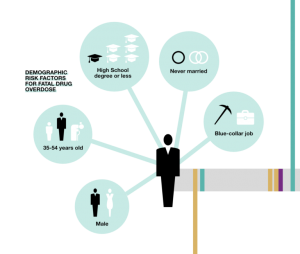

We wanted to see who these individuals were. Divide them through gender, age groups, ethnicity, and race.

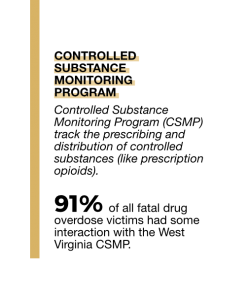

What kind of jobs that they have? Did they actually have insurance? What type of insurance? What were their earlier life experiences? Did they call 911? Did EMS respond? If EMS responded, were they given naloxone [the overdose reversal medication]? Was it appropriately recognized that these people were having an overdose? These were some of the factors including direct interaction with what we call in West Virginia the Controlled Substance Monitoring Program. Were they filling prescriptions?

What kind of jobs that they have? Did they actually have insurance? What type of insurance? What were their earlier life experiences? Did they call 911? Did EMS respond? If EMS responded, were they given naloxone [the overdose reversal medication]? Was it appropriately recognized that these people were having an overdose? These were some of the factors including direct interaction with what we call in West Virginia the Controlled Substance Monitoring Program. Were they filling prescriptions?

And then we go back to after their death, how many different types of drugs did they have in their blood? Did they have a lot of coexisting benzodiazepine [a sedative] and opioids that they were prescribed? But also were they incarcerated? Did they interact with health insurance claims? These were some of the things that we looked at in order to develop this social autopsy.

Unexpected Findings

PAYNE: Within the results, what was maybe one thing that you anticipated finding that you did find? And what was one thing that maybe you found that you did not expect to find?

GUPTA: I’ll start with what we did not expect to find. We found that four out of five people who died in 2016 because of a drug overdose actually interacted with at least one of the health systems. Men were twice as likely as women to die from a drug overdose. But women were 80 percent more likely than men to use all the health care systems within the 12 months prior to that death. As opposed to thinking that these individuals are junkies or excluded from the community, we found that majority of those who died from overdoses did interact with at least one of the healthcare systems. We found that sometimes they would interact with just one health care system before they overdose. That means for us a unique opportunity at the time of their interaction that we can actually take advantage and prevent the overdose in the future.

——— LISTEN ———

We also found that nine out of 10 of all the decedents had a documented history within the prescription drug monitoring program. That means they received a prescription. In the 30 days prior to their death, nearly half of the women decedents filled a controlled substance prescription and 36 percent of the men did the same. We found 71 percent of all decedents utilized emergency medical services within 12 months prior to their death. Those were some of the findings that we did not expect.

What we did expect was that we found a much more likelihood of decedents having Medicaid. Seventy-one percent of decedents had Medicaid in the 12 months prior to their death as compared to West Virginia’s overall adult population.

We also found that 56 percent of all decedents were ever incarcerated. That’s also something we have seen in other data sets across the country. And we confirm that decedents were at increased risk of death within the 30 days after the date of release. Especially decedents with only some high school education.

We also found that 56 percent of all decedents were ever incarcerated. That’s also something we have seen in other data sets across the country. And we confirm that decedents were at increased risk of death within the 30 days after the date of release. Especially decedents with only some high school education.

We also found decedents were three times more likely to have three or more prescribers, as compared to the overall population in the controlled substance monitoring program. And if they filled prescriptions at four or more pharmacies, they were over 70 times more likely to have overdosed.

We also found that there were decedent more working in the blue collar industry industries that come with higher risk of injury that may be at much more increased risk for overdose deaths.

So these are some of the compelling findings that help us develop that social autopsy.

Preventable Deaths

PAYNE: So with all of this information–and there’s a lot more within the report than you listed–how do you go forward and act on this immediately? Do you feel that you have the ability now to target specific programs to these individuals within the profile that you’ve gathered?

GUPTA: The understanding of people who are dying is fundamental to enhance the work of our programs.

To give you another example, we found that when people called for help — about 70 percent of decedents utilized emergency medical services — only 31 percent of decedents had naloxone administration documented in their EMS record. The critical piece to address the problem immediately is to help people at the time of overdose. It’s critical to understand that overdose deaths are pretty much preventable. Only when people enter treatment can we prevent them from dying. It’s the first step to treatment and recovery and re-entry into the workforce.

——— LISTEN ———

When primary providers, behavioral health providers, and others are seeing patients at clinics, we can show them these risk factors for overdosing and dying. So it’s important to utilize this data to share with practitioners to identify those risk factors just like we talked about heart disease.

We’re also working actively with our partners at the Department of Corrections to ensure that the reentry programs are enhanced to get these individuals the best care they can get because of the high rates of death after release. If they do suffer from a substance use disorder, their threshold declines while incarcerated. And when they come out, they utilize the drug, they are much more at risk because they will take more than their body will allow.

Similarly, there’s a lot of opportunity to expand the availability of naloxone to the first responder community. And it’s also being utilized in a variety of scenarios keep people alive and hand them off to treatment centers.

There’s also the effort to ensure that there are resources available in order to accomplish this. We assembled a group of national and regional experts from West Virginia University, Marshall University, and John Hopkins School of Public Health to bring together a opioid response panel that worked over about 45 days and took in a tremendous amount of public input and developed a set of 12 evidence-based recommendations to address the crisis.

Response

PAYNE: As you’ve presented this data to physicians and the correction officers, what has been the response so far?

GUPTA: I think the initial response Aaron has been either ‘Wow. I now understand the severity of the crisis and we must do what we can with all hands on deck approach to address this’ or ‘Let’s implement programs and find the resources — wherever they may be — in order to make this happen.’

Another piece that is going to be very critical and is still already helping us is the state of West Virginia received its 1115 substance use disorder waiver for Medicaid. I mentioned that we had 71 percent of the decedents had Medicaid status in the 12 months prior to their death.

——— LISTEN ———

PAYNE: You touched on the opioid response plan that was recently presented to the governor. How does the data that you collected from the overdoses edify that plan?

GUPTA: We want to have policies that are based in evidence and driven by data.

In prevention, we found a very clear link between people having the ability to have controlled substances through the controlled substance monitoring program and then a disproportionately high rate of decedents who have filled their prescriptions. So what we want to do is make sure that we are working very closely with our colleagues about pharmacy and Board of Medicine to ensure that there is a limited duration of initial treatment without compromising those who need the prescriptions for legitimate pain.

One of the things we also recommended: a wider dissemination of support access and referral. We have a helpline. It’s 1-844-Help-4-WV. Help is available.

One of the things we also recommended: a wider dissemination of support access and referral. We have a helpline. It’s 1-844-Help-4-WV. Help is available.

We also worked with our law enforcement partners and the judicial system to consider models such as diversion programs. There’s a lot of work happening because even the law enforcement side sees this as a public health crisis. Getting individuals access to treatment and sustained recovery is the best way to get them back in the workforce rather than putting them in prison.

As I understand, 37 inmates equals $1 million of expenditures per year. Around 33 correction officers equals $1 million of expenditure for West Virginia a year. So it makes sense to get people to help they need in order for them to enter recovery.

Treatment is critical and by expanding the ability to link nonfatal overdosing individuals to treatment and then expanding those treatment opportunities is critical.

Broader Lessons

PAYNE: While the data focuses on West Virginia, is there any are there any lessons within the report that you think could apply to neighboring states?

GUPTA: I certainly think so. I think you’re going to find very similar reasons for overdose deaths in our neighboring states. We as a region struggle with similar challenges. When we found the incarceration rates of those who died was high, we’ve seen similar numbers come out of Knox County, Tennessee. While we’re divided by boundary lines, we’re the same people. And there’s a lot of overlapping aspects of this.

This is just one step in our ability to work to counter this. This particular epidemic does not respect county lines, city lines, state lines.

——— LISTEN ———

PAYNE: West Virginia is facing arguably the worst of this opioid crisis. The focus tends to be on overdose deaths and that is prevalent in the fatality report. But what positives do you see in the in this report?

GUPTA: Aaron, there’s a lot of positive aspects. First of all it helps us enhance our ability to pick out those individuals who may be at a high risk as opposed to others. I will say that if you prioritize all you prioritize none.

We need to learn the risk factors related to the chronic disease of addiction. This is one way that we can understand what their lives were about, learn the risks that went unrecognized, and use that data to prevent future deaths from happening. We continue to lose in this country 130 to 140 Americans every single day.

We need to learn the risk factors related to the chronic disease of addiction. This is one way that we can understand what their lives were about, learn the risks that went unrecognized, and use that data to prevent future deaths from happening. We continue to lose in this country 130 to 140 Americans every single day.

Developing the data allowed us to work with our traditional and nontraditional partners. We were able to gather data from Corrections, Board of Pharmacies, and Board of Medicine. There was a lot of teamwork with Centers for Disease Control. So this was certainly not just work at the Department of Health and Human Services. That allowed us to gain from the knowledge and interact with national experts and also develop them as a resource in order to bring the best science and data to move forward.

PAYNE: And is there anything additional about the fatality report or the response plan that I didn’t ask that you want to mention.

GUPTA: I think with the recent announcement by Gov. Jim Justice of opening our Office of Drug Control Policy and Dr. Michael Brumage [the new director of the office] to lead it we’ll have a great opportunity to implement the opioid response plan going forward and be able to yield results that we have not been able to recently. I think we’ve developed the basis and the science, as well as the recommendations. I am fully confident that –as implemented– these 12 recommendations will certainly have the greatest potential in changing the face of this epidemic in the state and across the region.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

This article was originally published on Ohio Valley ReSource.