The slogan for Estill County is “where the bluegrass kisses the mountains.” But since 2015 the county, population 15,000, is widely known as the place where radioactive material generated by the oil and gas industry in a process known as fracking was dumped near some schools.

As the Ohio Valley ReSource reported in 2016, tons of waste from the drilling practice known as fracking was hauled from state to state before being improperly disposed of in a county landfill not designed to hold radioactive material.

This week the Concerned Citizens of Estill County and state officials squared off over how to best deal with the tons of radioactive waste. The landfill owners have been fined and are required to create a mitigation plan. Officials with the Kentucky Energy and Environmental Cabinet want to keep the waste in place. But local residents have a different idea. In the two years since the waste was discovered the community has come to a consensus on what should happen with the illegally dumped waste: Dig it up and move it out.

Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Concerned Citizens member Tom Bonny said he first thought keeping the waste in place was the better solution. But when he considered the long-half life of the radioactive material coupled with its location near Estill County’s schools, he thought of the long-term consequences to the community. He is also concerned about the proximity of the landfill to the Kentucky River and potential danger to the water supply not only in Irvine but downstream. So, he changed his mind.

He said most folks he’s talked to feel the same way. “The majority of the people I have spoken with indicate they will not have full peace of mind if it is left in place,” he said.

The disagreement over how to deal with the mess is just a small part of a larger problem with a lack of regulation, oversight and monitoring of this difficult waste. And years after Estill County’s crisis brought attention to the matter, experts say little has changed to prevent similar incidents.

“Forgotten Stepchild”

Nadia Steinzor researches fracking waste for the non-profit environmental advocacy group Earthworks. She said the gas industry produces thousands of tons of “hot” waste and companies and state regulators throughout the Ohio Valley and theMarcellus Shale gas region struggle to find safe ways to get rid of it.

She said there is an ever-increasing volume of such material entering landfills across the country, often without the full knowledge of folks living closest to the landfill.

“It’s kind of the forgotten stepchild of the oil and gas shale boom and it’s something people need to be more concerned about,” she said. “The environmental impacts are very pernicious and it is increasing in volume and increasing across the landscape.”

Steinzor said the difficulty in tracking waste as it moves from state to state is compounded by the fact that many landfills are owned by private companies. This is especially important in places like Ohio and Kentucky which receive large amounts of waste from other states.

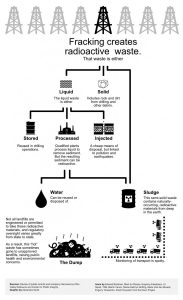

(Story continues below graphic)

In 2016 Center for Public Integrity reporter Jie Jenny Zou documented a spotty patchwork of state regulations across the Appalachian Basin that created the conditions for improper disposal of the waste.

Steinzor said it’s crucial for people living near landfills to be aware of what’s being dumped there.

“There was one gentlemen in West Virginia who has been tracking what has been coming into that landfill there,” she said. “The guy stationed himself at the landfill entrance and asked every truck where they were coming from. He found they were coming from places generating oil and gas waste.

“That’s one way to find out!” Steinzor said with a laugh.

She said that while the tracking of fracking waste has gotten more attention since the problems became known in Estill County not much has changed as far as policy is concerned.

“From a regulatory perspective, the policies and mandates and requirements that the industry has to adhere to are still lagging behind.”

Vigilant Communities

Estill County resident Rhonda Childers has been concerned about contamination at the landfill for 20 years. She was part of a group of activists who helped get rules in place to keep out radioactive material. But as the landfill changed owners those rules were forgotten or ignored.

“We let our guards down and we just kind of ignored this,” she said.

Childers said Estill County’s experience stands as an example to other communities to be vigilant about what is happening at local landfills.

“Today we are talking about Estill County, tomorrow we could be talking about… any county in the state of Kentucky,” she said.

If the condition of state laws and regulations is any indication, it’s also something that could happen at any number of landfills around the Ohio Valley.

This article was originally published on Ohio Valley ReSource.