At a recent conference in Lexington, Kentucky, economists and community leaders gathered to talk about the state’s current budget crunch and possible economic future. Peter Hille, president of Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, said Kentucky and other Appalachian states need to do more to build a new economy and move from dependence on a single source.

“Because coal played such a dominant role, it took the oxygen out of the room for the development of other sectors of the economy,” he said.

MACED, as his group is known, works to increase economic alternatives in Appalachia and partners with the Appalachian Regional Commission. Hille said the region’s vision for a new economy needs to be more just, sustainable and diverse. He says that means not replacing one big industry with another one and instead looking at a range of economic opportunities.

CREDIT JEFF YOUNG / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

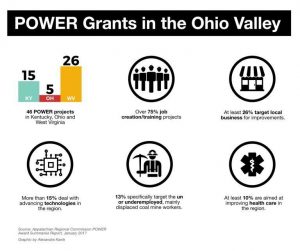

That’s part of what the ARC is trying to foster with the latest $20 million round of funding for its Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization projects, or POWER grants. But a new study commissioned by the ARC shows just how hard it will be for the region to recover from coal’s collapse.

Driving Diversification

POWER grants supported 46 projects between 2015 and 2017 ranging from learning computer coding to developing the tourism industry. Last year the White House’s budget proposed eliminating funding for the Appalachian Regional Commission, but regional Congressional leaders pushed back and kept ARC’s funding intact. It’s unclear if the White House will seek to zero out funding in its next budget.

Meanwhile, the ARC is requesting new proposals for projects to diversify and grow the region’s economy and has scheduled workshops and webinars in the coming weeks to encourage applicants. The commission also released a thorough study of the cascading effects of the coal industry’s downturn in the region, An Economic Analysis of the Appalachian Coal Industry Ecosystem.

“We have people who would like to work in a perfect world, but they don’t have the education or the training or the skills to get a job so they don’t even bother to look for work in the first place,” Director of West Virginia University’s Business and Economic Research, John Deskins said.

Credit Rebecca Kiger / Ohio Valley ReSource

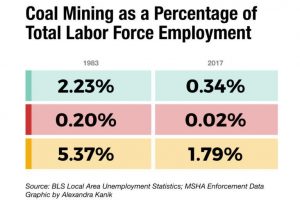

The ARC study he helped conduct finds the labor force has declined substantially, especially in the prime working-age population in central Appalachia. Job markets in Kentucky and West Virginia have an especially hard time absorbing coal workers into other sectors of the economy because a miner’s skills don’t transfer well to other work. Deskins said Appalachia needs to invest more in educating and retraining people in order to attract new businesses.

“It doesn’t matter how good the tax climate is or how good the regulatory environment, or how good infrastructure is,” he said. “A business will not locate here if they can’t find the workers that they need.”

Vicious Cycle

The study also found a vicious cycle at work. As the economic base in Appalachia suffers, state and local governments have fewer resources for the education needed. Deskins said part of what made the decline in the coal market so difficult for the region is that there were no other industries or other sectors of the economy that were growing to offset the losses. He said Appalachia needs to supplement and diversify its economy with a broad range of industries from manufacturing to tourism and food.

Brian Lego, a co-author of the ARC report and a researcher at West Virginia University, agreed.

CREDIT REBECCA KIGER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

“So you do have some diversification, but it’s not to the extent that’s been needed to offset what’s occurred as far as the coal jobs that have been lost over the past several years,” he said.

Lego said part of the challenge is what were once considered advanced skills are now basic ones needed for a lot of industries. He said it’s not just miners who are affected, it’s the entire supply chain of the coal industry.

“Not only is less coal being demanded, but as these coal plants retire you have the impact of less coal being mined but also less coal being transported,” University of Tennessee researcher, Mark Burton said.

Isolation

Burton said the mining troubles ripple throughout the region. For example, as less coal is hauled more freight workers will need to be retrained as well.

“The railroads that operate in the region have already taken a number of steps to reduce their investment in the region,” he said.

Burton said the region’s physical isolation also cuts off commercial and cultural ideas and educational opportunities. He said the initial design of the interstate system left out much of Appalachia because of the difficult terrain, something the ARC worked to change with an early focus on roads and physical infrastructure.

But despite the challenges, he said, Appalachians have some things going for them.

“Appalachians in general are very stubborn, they want what they want and will work for it and wait for it more than almost any other segment of the population,” Burton said.

CREDIT BENNY BECKER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

Looking to the Future

Burton said people are realizing that coal is not going to come back and be the economic driver it once was. Peter Hille with MACED said the question is not how to bring back coal jobs but how to build new jobs. He said talk of bringing back coal is a distraction from the real work that needs to be done.

“Building a new economy that goes beyond the past, honors the heritage that we have in this region, but really looks to the future that we want for our children and our grandchildren,” Hille said.

This article was origianlly published on West Virginia Public Broadcasting.