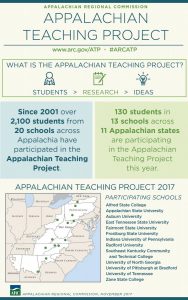

Students from across Appalachia presented their ideas and solutions to some of the challenges faced by their communities at the Appalachian Regional Commission’s “Appalachian Teaching Project” conference in December. Projects ranged from “Assessing Riparian Health and Land Use on the New River of Ashe County, NC” (Appalachian State University) to “Connecting Built and Natural Environments: A Vision for Preservation, Sustainability and Growth in Canaseraga, New York” (Fairmont State University). You can find a list of all the projects with their brief descriptions here.

I attended the second day of the conference, witnessed some great performances and spoke to participants about their views on issues often found in the headlines these days. The two man I spoke with represent an intersection of academia and the coal industry, the most iconic sector of Appalachian economy. Their collective knowledge and experience make them some of the most reputable spokespeople for the region.

Tim Price and Robert Gipe from Harlan County, Kentucky, were kind enough to sit down with me and talk about their frustrations, hopes, victories and failures in their hometown, as well as what they do to improve it.

Our hope is to follow up with a visit to Harlan County in the near future, bringing our readers an update on their efforts. In the meantime, their unique perspective offers some insight.

***

Robert Gipe is the director of the Appalachian Program at the Southeast Kentucky Community Technical College in Cumberland. Tim Price is his student and a coal miner with over seventeen years of experience.

Their paths crossed during a recurring university course, in which students focus on some aspect of sustainable economic development in Appalachia. In 2017, the students were working on an individual idea on how to develop the county economically, as well as on a project focused on downtown redevelopment in Harlan.

An old department store that was donated to a local non-profit became the focus of the project and students, together with Robert, engaged designers, architects and urban planners to push what he referred to as the “community space activation process” into motion, accompanied by art and cultural events.

Tim and Robert represent different, intertwined layers of issues faced by citizens of Appalachia. Those are not necessarily problems unique to the region. They might be more severe at times, or more area or industry-specific, but still remain rather universal — fleeting jobs or shifting economy, and technological labor automation that outpaces government’s ability to respond.

Tim: I’m one of Robert Gipe’s students. I was a coal miner for 17 and a half years, and job layoffs forced me into job training. So, I wanted to go and further my education. I represent not only Southeast [Technical College], but I represent the coal miners in Harlan County … This county thrives on coal, this county was built on coal, and long time ago the government came and helped the miners when there was a big crisis. But in this day and time we’re having a crisis in Harlan and it’s like the government has not stepped in like they used to. So, Robert Gipe and those kids, and a lot of other people, that’s involved in this … This is like life, this thing that we’re doing, that little business here.

The college is engaged in three distinct projects that, among other things, aim to train designers, as well as support entrepreneurs interested in online retail and marketing of their products. Robert explained to me that the third project, redevelopment, has multiple facets. It’s designed to activate the community, train construction workers in new building technologies, as well as hospitality workers in being more effective in promoting that community. The end goal is to have a workforce that’s ready to step in, do the work and remain in Harlan, finding employment with future construction projects.

Robert: … I think for our college, that if we don’t get involved with the community development and economic development there’s not going to be a market for the college either.

Our college has supported the coal industry. We have done training for coal miners for a long long time. We’re there for the community and without the community we’re not going to be there. So, it’s interesting. In some ways it’s rough but in some ways it’s exciting because now we can be all kinds of things, you know, but the transition is difficult and I don’t think any of us have an answer. Somebody told me there’s no silver bullet, just a bunch of silver bbs.

Tim was very quick to point out that Harlan’s problems don’t exist in a vacuum. Other towns and other industries depended on the coal coming from their town and, as the steady stream turned into a trickle, other communities suffered as well. I noticed Tim’s ability to translate problems he was describing into compelling metaphors. He talked about a buffet with a line of 100 people, but with food only for 80. He pointed out that not only 20 people will end up with empty stomachs, but the closer to the end of the line, the slimmer the pickings and hungrier the public. According to Tim, that’s the effect that the dying coal industry in Harlan has on its neighbors.

There’s a very real conflict between “here and now” needs of the community and the long term planning.

Robert: First thing, this isn’t a game. It’s not like an academic exercise. The urgency, I mean, this is like next 30 days, next 60 days, 90 days, if something’s not going to happen, Tim is going to leave.

Tim: It’s gotten to a point where we’re trying to live to the next day, that’s why I was talking about that buffet. You’re just trying to make it to the next day until it comes time to say: “All right, I have to leave, there’s nothing that’s gonna give here.”

Robert: I think for us, at the college, one of the things is you wanna do smart programming. You don’t want to waste this grant money and sometimes that means you have to do things that don’t pay off in 30, 60, 90 days […] And one of the hardest things is, you know, I want Tim to be around, I want him around next semester and a semester after that. And I want him to be earning. But at the same time we’re trying to do things that it’s going to take a year or two years before … it’s even a possibility it’s going to pay off … How do you stay calm and make smart decisions and use these very limited resources well, in a way that’s going to pay off in a long haul when what you want to do is put money in people’s pockets and stop the pain that’s in front of you.

Tim is not optimistic, but he keeps on going and refuses to give up. He told me that his heart is in Appalachia and he’s not interested in leaving. He recognizes, however, that circumstances might force him to do so one day. Robert, Tim and other students, along with the people of Harlan, are taking responsibility for reinventing the local economy. It wasn’t their choice, but they don’t shy away from the challenge.

What struck me were their extremely conservative expectations. They weren’t pessimistic, but the healthy dose of skepticism could be detected at every stage of our conversation. The irony of the whole situation didn’t escape them either.

Robert: I got hired to teach these guys their history, I got hired … to do arts in the community, I mean, knowing that this would be a hard hit community. But, you know, we had some success, and now we’re being asked to reinvent the economy of the community. We’re just a bunch of little hippie college professors, we don’t know how to do this stuff but we’re getting thrown into that and I think … that by throwing us all together like fate has, you realize that, as a community, we have something in common, that we’d really like for this place to be a good, easy place to live. And so, we’re just like “well, I guess we just might as well try and figure it out,” but … I think people gonna keep leaving for a while.

It’s hard to be an industrial recruiter. We’re talking with a guy who does that in our county and one of the things he said was … when we talk to companies, first things they look at is “is our family going to be happy here?” and so all these quality of life issues are important to that process. We … got to hear where the county’s leadership is, we had industrial recruiter talk to us, we know what his needs are and we’re doing what we can and I think it’s in that quality of life area. So, I think that’s critical to bringing in business and even having local businesses feel like there’s a reason to stay. I think we’re doing our best.

When speaking to Tim, you can sense his bitterness. He believes it is primarily the Environmental Protection Agency that’s responsible for the loss of his job. But he didn’t display any romantic or nostalgic attachment to the coal industry. He is angry with the government for failing to provide any alternatives. During our conversation he mentioned new possible designations for closed mines, always with a pragmatic, non-ideological attitude.

The general sentiment is that of being left behind. While some of Tim’s grievances echoed the talking points of the current Administration, he never questioned popular science or denied demonstrable changes to the modern economy, such as pollution and climate change or the impact of new technologies on mining.

The problems of Harlan County, represented in this case by Tim’s problems, come from what could be described as exploitation by industry and recklessness of the government.

Tim: Auto industries got bailed out, (the government) stepped in, “All right, we’re gonna help you.” So nobody helped the coal miner, nobody helped coal companies. Nobody stepped in and said “hey, you don’t have order for these trains, we’re gonna step in and turn your coal mines into a factory, turn some of these sites, these strip jobs, we’re gonna turn them into windmill power plants … at least have something for these families to fall back on.”

Inevitably, we end up talking about Trump’s big plans to save the domestic coal industry. I ask Tim about his views and about the views of the community he knows, because I don’t believe that Appalachia, or any other place in America dubbed as the Trump country, is a solid block of beliefs. We know the President is popular in Kentucky and we know he won Kentucky’s electoral college, but we are also told that the faith in his promised policies is unwavering. Tim is just one example that proves otherwise.

Tim takes what Donald Trump often sees as a point of pride — his business acumen — and uses it to explain why he doesn’t think “bringing back coal” is a viable option for Appalachia.

Tim: He can draw you a bigger picture and make you believe whatever he wants to make you believe, but the simple fact is, if he was a big power plant owner and he had to pay $2 billion to switch over to gas … Now, think about this, he’s a billionaire, is he going to spend two more billion to switch back over to coal? And his labor cost is gonna go up, and he knows it. Is he gonna lose more money? Do the math, you know what I mean? … I don’t feel like the people in Harlan are happy with him right now. He’s out flying around, visiting other countries when he should be working on the heart of America. I just feel like he’s dropped the ball. And I feel like there’s not going to be an easy solution and we have to stand up and try to reverse that.