Imagine living and working somewhere designed to fit a couple hundred people. Now picture that same space crammed with twice that number. Madison County, Kentucky, Jailer Doug Thomas doesn’t have to imagine it. He lives it.

“I’m doing all that I can with what I have to work with, which is not a lot,” he said. “Because we’re a 184 bed facility with almost 400 people.”

Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

According to the Madison County jail task force, roughly 80 percent of the people incarcerated there are jailed on charges that somehow relate to addiction. County Judge Executive Reagan Taylor wants to try a different approach.

“It didn’t take long looking at our statistics to realize that we really didn’t have a jail problem, that we had a drug problem,” he said.

Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Taylor is looking into expanding the current jail for the county just south of Lexington. But he also wants the county to partner with private companies to build what he calls a healing center. People whose charges stem from a substance use disorder would be diverted to the treatment facility instead of going to jail. It’s part of a small but growing trend in the region’s law enforcement agencies to find creative approaches as the Ohio Valley’s opioid crisis pushes jails beyond capacity.

Dollars and Cells

Taylor said a new 800-bed jail would cost his county about $50 million and it would still likely be full in about ten years. He said because so many are in jail for drug related charges, a treatment center seems like a better return on investment.

“We’ve got to spend money one way or the other,” he said. “So do we want to spend money to where we just have to continue spending money and kicking the can down the road, or do we want to spend money to where we have a solution?”

Taylor said the healing center would provide long-term rehabilitation that would help people get back on their feet. Taylor wants it to be more than a basic detox facility. The center would include peer support, life skills, and education or vocational training. Taylor said he wants people to be able to become tax-paying members of their community again.

A Second Chance

Eric Hudnall, of Athens, Ohio, was prescribed opiate painkillers after a car accident left him with a painful neck injury. He became dependent on the pills and soon, a growing addiction and some bad social influences led to his arrest for breaking into a home. That landed him in front of a prosecutor who opted to offer Hudnall a drug treatment facility instead of jail.

Hudnall said that because he was honest and spoke up about his addiction he was given a chance to turn his life around.

“As long as you’re truthful with people you’re going to get help,” he said. “Now, if you hide stuff and you lie to them and they find out about it, they’re not going to trust you and they’re not going to help you.”

Hudnall said he was almost homeless when he entered the treatment program. Now he has a place to live, a steady job and a car.

“If it wasn’t for the prosecutor’s office or Health Recovery Services I’d probably still be addicted to opiates or even in prison,” he said. “Everybody deserves a chance.”

There are a lot of people in the criminal justice system like Hudnall who are incarcerated because the need to feed their addiction led them to a crime other than drug possession.

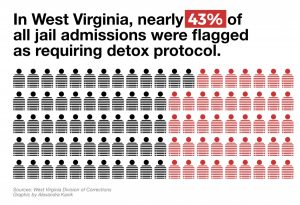

In West Virginia, for example, only 12 percent of the prison inmates were charged with a drug possession charge. But about 43 percent incarcerations in the state’s jails required substance abuse treatment of some kind in 2016.

In West Virginia, for example, only 12 percent of the prison inmates were charged with a drug possession charge. But about 43 percent incarcerations in the state’s jails required substance abuse treatment of some kind in 2016.

Economic Appeal

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, one year of methadone or medically assisted treatment costs about $4,700. That’s one-fifth of the cost to incarcerate one person in the Ohio Valley for a year — a $25,612 cost on average.

Warren County, Kentucky, Circuit Judge Steve Wilson, who has worked in the legal field for 35 years, said that economic argument is appealing, even for some prosecutors and judges who favor a tough “law and order” approach.

“Truly a tremendous driving force is the fact that economically it’s much better trying to treat people than it is to incarcerate people,” he said. “Because at the end of incarceration without treatment we still have the same problem.”

Wilson said the criminal justice system is often the first chance someone with substance use disorder has at getting treatment. He said prosecutors and judges need to be patient. They may well see the same offender more than once. Although it can be frustrating he said they have to try.

“I’ve always been afraid that once we send somebody off to prison we really have a feeling it’s not our problem anymore. We’re still paying for them,” he said.

ReSource reporters Aaron Payne and Mary Meehan contributed to this report.

This article was originally published on Ohio Valley Resource.