Pundits are watching the Virginia governor’s race for signs of what might transpire in 2018 around the country. Neither Republican Gillespie nor Democrat Northam did well with rural voters in their primaries. But if the metropolitan voting is close, the margin of the Republican’s rural victory could help determine the winner.

Although Virginia’s rural voters have waned in population, economic strength, and political influence, they may tip the scales in next week’s gubernatorial race between Republican Ed Gillespie and Democrat Ralph Northam.

Republican Gillespie will win rural Virginia, but the margin by which he does may affect the statewide result. That flies against the last decade of conventional wisdom, which holds that Virginia is turning blue because Democratic-voting urban areas in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads have grown faster than rural areas.

Both Gillespie and Northam have targeted those voter-rich urban and large suburban regions. Neither did particularly well in rural Virginia in their respective primaries, in which each faced populist insurgents who carried significant majorities of the commonwealth’s non-metro regions.

Yet if the race is close, rural voters could indeed make the difference. (An average of statewide polls has Northam favored by 3.3 points, though the most recent one has Northam favored by 17 points.)

“Margins matter,” said Geoffrey Skelley, associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia Center for Politics. “If Democrats lose Southwest Virginia by 30 points, it’s one thing, but it’s another if they lose by 40.”

The relative impact of rural voters will also depend on the turnout in urban areas.

“If turnout isn’t as good, relatively speaking, in metropolitan areas, and Gillespie is running up margins like Donald Trump had in Southwest, Southside, and the more rural parts of the state, that could leave Northam in a really tough spot,” Skelley said.

Because Virginia tends to mirror the national popular vote in presidential years, political observers often look to its gubernatorial race as an indicator for what’s to come. That’s especially true this year, as pundits have examined other statewide races like Alabama’s special Senate election for signs of what might happen in 2018. There are dangers in over-generalizing the politics of a single state. But because Virginia is a battleground state and one of only two gubernatorial contests this year (the other is in New Jersey), it will be heavily scrutinized for any signs that might indicate what’s to come next year.

This year, the rural/urban divide has attracted particular attention, with much of Gillespie and Northam’s final debate—staged in Appalachian coal country—devoted to that topic.

Northam, who grew up in the largely rural Eastern Shore, has floated policy proposals targeted at helping rural Virginia’s slow-growth economy, particularly in the state’s Appalachian region, by expanding higher education and offering tax breaks for start-up companies. Yet he has visited rural Virginia less than previous Democratic gubernatorial campaigns, even breaking a long-running political tradition by opting not to march in the Buena Vista Labor Day parade—although he did attend the party’s breakfast before the parade itself. That decision led the chairman of the Democratic Party in Rockbridge County, where the parade takes place, tobriefly resign in protest. Northam has caught flak from rural environmental activists for not actively opposing a pair of proposed natural gas pipelines, and he’s been criticized for not doing enough to pursue voters of color, who are a significant cornerstone of Democrats’ coalition.

Republicans dominate rural Virginia, which lends Gillespie an inherent edge in those areas. Gillespie has his own policy prescriptions for rural Virginia’s ills, mostly built around a tax cut that’s central to his platform. But he too has challenges. During an Abingdon rally featuring Vice President Mike Pence, Gillespie’s campaign did not allow former Trump campaign staffer Jack Morgan to appear, according to the Washington Post, which irritated some locals. Gillespie grew up in a New Jersey township but is very much a creature of Washington, D.C., having spent a significant portion of his career there as a congressional aide, lobbyist, and Republican Party official.

Rural Virginia once dominated state politics, but over the last 30 years, its influence has waned considerably. The national shift to a mechanized, global economy has devastated small towns and the countryside. Tobacco, a significant economic driverwhose historic importance to Virginia was symbolized by a golden tobacco leaf painted in the dome of the capitol when it moved to Richmond, has fallen on tough times, beginning with a gradual decline in production in the 1960s, and continuing through the end of the quota system in 2005. The textile and furniture manufacturers that made Southside Virginia an economic powerhouse through the 20th century have closed up and moved overseas. And the coal sector, which for well over a century carried Appalachian Virginia, has fallen on what looks to be permanent hard times.

In 1985, Douglas Wilder, Virginia’s first and so far only African American to be elected to statewide office, won his race for lieutenant governor in part by spending extensive amounts of time in Southwest Virginia. Four years later, running for governor, he met with striking miners there. Through the ’90s and ’00s, however, the region increasingly voted Republican.

When Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, Virginia’s two Democratic U.S. Senators, won their gubernatorial races in 2001 and 2005, respectively, the path to statewide victory for Democrats involved running up the score in the urban crescent while keeping the margins reasonably close elsewhere. Campaigning in those rural areas not only built enthusiasm among the Democratic voters there, but it also provided coattails for Democratic elected officials in Congress and the General Assembly.

Backlash against President Barack Obama, however, effectively wiped out elected Democrats in the General Assembly and Congress, along with the local party organization that had supported them. At the same time, Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads were growing rapidly and voting more and more in favor of Democrats.

Virginia’s demographics have effectively changed to the point where many strategists think Democrats’ smartest bet is to focus almost exclusively on urban and suburban areas. Campaigning in rural areas with fewer voters, who are going to vote Republican no matter what, the thinking goes, is a waste of time.

Those trends, long in the making, spiked in 2016.

Election results in the 2013 governor’s election and the 2016 presidential election show a vast political chasm between rural and metro Virginia. In urban and large suburban counties, Hillary Clinton won more than 55 percent of voters compared to fewer than 40 percent for Trump, which outpaced the 2013 Democratic gubernatorial nominee, Terry McAuliffe, who won his race. Likewise, in medium-sized suburbs and non-metro counties, Donald Trump ran better than the 2013 Republican gubernatorial nominee, Ken Cuccinelli. In the most rural counties—non-metro counties that don’t touch a metro area—Trump outran Clinton 72 percent to 25 percent, nearly 10 points better than Cuccinelli’s 62/38 margin over McAuliffe.

“Some of it came down to Trump’s appeal and Clinton’s lack thereof, and to some degree these were shifts we’ve been seeing,” Skelley said. “Southwest and rural Virginia had been trending Republican for the most part, but I think the trend took a big leap in 2016. The 2016 contest fortified what had been ongoing trends.”

Gillespie and Northam both entered the gubernatorial race before the 2016 election took place, and each became his party’s more centrist, establishment candidate in his respective primary. So there’s reason to think those 2016 margins might shrink. It’s also possible that the presidential election set a new normal for polarization that will extend to state-level races, and indeed, both candidates have tried to move voters by invoking national politics.

Turnout for off-year elections tends to be significantly smaller than presidential elections—somewhere between half and two-thirds of the number that turns out when the White House is up for grabs. That off-year voter population tends to be older and whiter—and therefore more conservative, which benefits Republicans and gives lie to the idea that Virginia is automatically a Democratic state, at least just yet.

Neither Gillespie nor Northam seem to bring out strong passions in Virginia voters. They’re essentially mainstream candidates that neither excite their own base nor strike fear into the other side’s base—although both have tried. Northam has taken a page from his primary opponent, former congressman Tom Perriello, and run nearly as much against Trump as he has Gillespie.

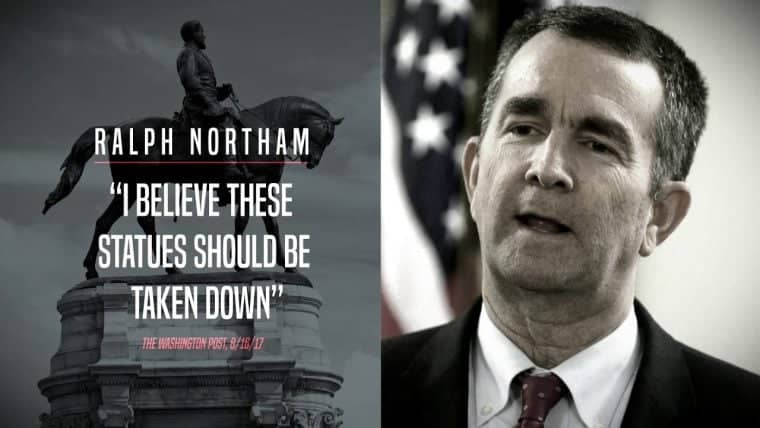

Democrat Northam’s support of removing Confederate monuments has been a campaign point for Republican Gillespie. Gillespie, meanwhile, has spent the campaign trying to straddle Virginia’s political divide. In Northern Virginia his campaign materials portray him as a solutions-oriented moderate Republican. In rural Virginia, especially in the southwest corner of the state, Gillespie has borrowed from his opponent in the Virginia Republican primary, Prince William County board chairman Corey Stewart, and from President Trump. Even as Gillespie has essentially ignored Trump’s supportive tweets, his campaign has attacked Northam on Confederate monuments and being soft on crime, immigration, and restoration of rights for felons. In the primary, Stewart was regarded as an underdog to the point that he was mocked for his relentless focus on Confederate symbols, yet he defeated Gillespie in Appalachian Virginia by more than 15 points and fell just short of beating him statewide, effectively demonstrating that Trumpism has legs with the Republican base.

“Stewart’s success down there may be a result of him running on cultural conservatism through the statues issue, and obviously the strong anti-establishment feeling that Trump tapped into,” Skelley said. “That brand works well in that part of the state.”

Will aping that approach win Gillespie large enough margins to defeat Northam? We’ll find out on election night, Tuesday, November 7, when Skelley said he will not be watching indicator counties so much as regional margins stacked against last year’s.

“It’s going to be me looking at the votes by region and comparing them to what was going on in 2016, to get some sense of whether Gillespie is winning the rural areas compared to Trump, and how Northam is doing compared to Clinton,” Skelley said. “I’ll be watching to see who is outperforming or doing closely enough to win.”

Mason Adams is a freelance journalist from southwestern Virginia. He has reported for the Roanoke (Virginia) Times, 100 Days in Appalachia, Politico Magazine, Blue Ridge Outdoors, New Republic and Scalawag. Follow him on Twitter at @MasonAtoms.