The twisty roads winding through Appalachia can seem labyrinthine and intimidating to outsiders, but many residents spend an hour or more driving on them to get to work each day. As jobs and people have increasingly migrated to urban areas, those who remain in the many rural localities of Appalachia must spend more time on the road to reach work, school, groceries or elsewhere.

Appalachian commuters find ways to fill the time. For some, that’s listening to podcasts, audiobooks and music. Others schedule meetings by phone — which, of course, requires some knowledge of gaps and holes in cellular service.

Shilo Atkinson, who lives on Claytor Lake near Draper, Virginia, travels the East Coast between Maryland and Florida to different destinations for her job as a divisional level support nurse. Between work and traveling to practice with various roller derby leagues during the week, she drives an average of between 700 and 1,000 miles per week — mostly in the mountains.

Atkinson is not alone in traveling outside her home county for work. In fact, 63 percent of workers who live in Pulaski County commute outside its boundaries for employment, and 60 percent of those employed within its limits commute in from outside. Those patterns generally repeat across much of rural Appalachia, with as many or more people commuting in and out for work than remaining in their home county. The exceptions tend to be urban cores and college towns, which see many more incoming commuters.

“As employment opportunities have shrunk in rural communities, people are traveling farther and farther to get to where the jobs are,” said Jeremy Holmes of Ride Solutions, a western Virginia program dedicated to providing alternative transportation options, including carpooling, biking and public transit.

“When we’re looking at how we plan for commuter services, the trends we’re seeing is that demographic and economic development areas are really focused on urban cores, reuse, all of those sorts of things,” Holmes said. “To stay put in rural communities, more people have to travel to get jobs.”

The Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission, a regional planning agency that operates Ride Solutions, is studying the possibility of extending some form of public transit to the Alleghany Highlands to Roanoke’s north and Franklin County to its south. The study came about in large part because Amtrak is extending service to Roanoke later this year.

At the same time, however, the budget proposal from President Donald Trump’s administration calls for $2.4 billion in cuts to federal transportation projects, which affects Appalachia in more ways than one. The proposal eliminates a program that has improved nearly 3,000 miles in the region, as well as Amtrak service through Appalachia on a line that runs between Chicago and New York. The federal budget ultimately is decided by Congress — not the president — but Trump’s plan sets down a marker that serves both a starting point and his larger priorities.

Still unclear is how the proposed cuts fit into the president’s infrastructure package, hyped last week as part of “Infrastructure Week” by the White House. Although Donald Trump talked up a $1 trillion infrastructure package during the campaign, the legislation instead would use only $200 billion in federal funding to spur states, localities and private entities to ante up the rest of the money. Additionally, Trump’s infrastructure plan aims to slash what he called a “dense thicket of rules, regulation and red tape” slowing down project permits — which he illustrated by dropping thick binders during a news conference last week.

Back on the mountain roads, Atkinson’s job and hobby continue to rack up the mileage. Her nursing job takes her far from her home in Pulaski County, but she also travels to play roller derby a couple of times each week. For a while, she was driving two and a half hours to Charlottesville, Virginia, to skate with that city’s nationally ranked Derby Dames. More recently, she tried skating with the Appalachian Rollergirls of Boone, North Carolina, but the commute was too intensive given her work schedule. She still continues to travel to Roanoke on weekends to coach the Star City Roller Girls, the league with whom she started skating back in 2007 before splitting to form the New River Valley Rollergirls because she wanted to avoid the hour-long drive from her then-home in Narrows, Virginia.

Over the course of all that travel, Atkinson has witnessed some horrendous wrecks.

“For people like myself who do travel, it’s not uncommon to see accidents,” Atkinson said. “Sometimes they stay with you for a little while. You learn to truly respect the road and all of the terrible things that could happen while you’re out there.”

Wrecks on rural mountain roads don’t occur at the rates that they do in more congested, urban areas — but their impact may be felt just as deeply.

In 2015, a woman came off her overnight shift at a emergency veterinary clinic in Roanoke, visited her father and headed north on U.S. 220. She fell asleep behind the wheel and crossed into the southbound lane, colliding with another car and killing its two occupants. All three were traveling between homes in the Alleghany Highlands and jobs in Roanoke—a 50-plus-mile drive that takes between 60 and 90 minutes, often on two-lane road that winds through gorges and is dotted with memorials to loved ones lost in other, fatal wrecks.

In Alleghany County, Virginia home to the two men who were killed, more than twice as many people commute out of the county as those who commute in, and three times as many who both live and work in the county. Nearly 20 percent of its workers travel greater than 50 miles for work. Even Darlene Burcham, the city manager of Clifton Forge, said she commuted from Roanoke for her first 14 months on the job.

Even if these roads are safer than their urban counterparts, the sheer amount of time on the road and distances driven increases the likelihood of a wreck. It’s not just commuting workers at risk. As more Appalachian localities close and consolidate schools as they lose population, children are riding longer distances on school buses.

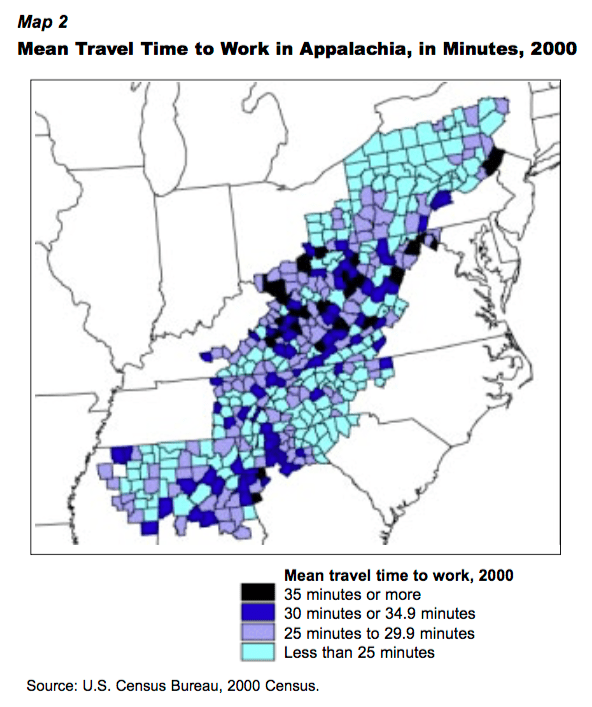

The Appalachian Regional Commission hasn’t studied the issue in recent years, but Mark Mather of the Population Reference Bureau produced a report on housing and commuting in Appalachia in 2004. He noted then that, based on 2000 Census figures, “Appalachian workers spent slightly less time traveling to work in 2000 than workers in the rest of the country….[but] workers in Appalachia’s Distressed counties had the longest commutes (28 minutes, on average). The time spent to commuting to work in Distressed areas in Kentucky and West Virginia was similar to that of the Washington, D.C. suburbs — one of the most congested areas in the country.”

Three of the five U.S. counties with the longest average travel times to work in the year 2000 sit in Appalachia, as defined by the ARC. Average commute times in Elliott County, Kentucky, Pike County, Pennsylvania and Clay County, West Virginia all exceeded 45 minutes.

Three of the five U.S. counties with the longest average travel times to work in the year 2000 sit in Appalachia, as defined by the ARC. Average commute times in Elliott County, Kentucky, Pike County, Pennsylvania and Clay County, West Virginia all exceeded 45 minutes.

Mather also noted a correlation between high poverty rates and long commutes in central Appalachia. In 2000, there were 46 U.S. counties where the commuting times averaged 30 minutes or more and where at least one-fifth of the population was living in poverty. Half of those counties were in Appalachia, mostly in Kentucky and West Virginia.

In his analysis, Mather blamed welfare reform for the increasingly long commutes in economically distressed localities, noting a geographic disconnect between entry-level job openings and the homes of the workers needed to fill them. Even in growing, prosperous localities — mainly located in southern Appalachia in counties on the outskirts of Atlanta — a related increase in housing costs forced many workers to drive farther distances.

The challenges presented by the need to commute for work are especially prevalent in southern West Virginia because of its topography and related effect on infrastructure, said Lillian Graning, chief communications officer for the New River Gorge Regional Development Authority, whose four counties have an average commute time of 33 minutes.

“The coalfields are still extraordinarily isolated,” Graning said. “It may be just a couple of miles away by GPS, but it takes a couple of hours to get there because of the mountains and valleys. Highway systems are still a need those communities are feeling the impact daily. School consolidations and lack of access to those highway systems turn some school bus rides into two-hour trips, both ways.”

The political and policy conversation about investment in new roads can be difficult, especially when framed about spending public dollars to benefit a smaller number of rural residents versus getting more bang for the buck in more populous areas. With West Virginia still grappling with a half-billion dollar shortfall in the state budget, new road construction feels even more distant.

So what about President Trump, who campaigned in part on that $1 trillion infrastructure upgrade? Many hope the Coalfields Expressway, a four-lane highway through southwest Virginia and southern West Virginia that’s been in the works since the ’60s, will be funded as part of that package, and other parts of Appalachia have their own transportation wish lists.

Although a list of 50 potential projects supposedly made the rounds among lawmakers and stakeholders earlier this year, Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao said in May that the infrastructure bill won’t include anywhere near that sort of specificity. White House officials also have told interest groups that the bill will take a conservative approach to avoid anything resembling the roughly $800 billion stimulus package passed in 2009.

With healthcare and tax reform still incomplete headed into the summer, it’s still unclear how infrastructure will fit into the congressional calendar. Congressional leaders will ultimately decide its fate, as well as that of the Trump administration’s transportation budget proposals.

Even if the infrastructure bill passes, many questions remain about how funding will be distributed. Its apparent reliance on matching funds may put the question back to states. In Virginia, which holds elections for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general and all 100 seats in the House of Delegates this year, only one candidate is talking about the state of Appalachian roads, and polls show him trailing in his primary.

In the meantime, workers keep driving ever-greater distances through Appalachia’s twisting roads. Economic trends don’t look likely to reverse that process anytime soon. The odometer continues to quietly — but steadily — run up the miles.

A native of the Alleghany Highlands, Mason Adams (@MasonAtoms) has worked as a journalist in the Blue Ridge Mountains since 2001. He lives with his family plus dogs, cats, chickens and dairy goats in Floyd County, Virginia.