Part 4 of 4: Remembering the Flood

On Friday morning, June 24, 2016, people woke up to heartbreaking news of West Virginia’s flooding. Roads had given out, cars were floating into houses, people were missing, stranded and the death toll was rising as the waters receded.

In Rainelle, four people had died. Most of downtown was underwater leaving homes and businesses destroyed. In the immediate aftermath of the flood, many jumped right into response mode. The Rainelle Medical Center provided free vaccinations and medical attention and church leaders got their congregations together to clean out homes. Appalachia Service Project built dozens of new homes and has plans for more in the future. Volunteer teams are still lodging in Rainelle’s church buildings to serve for weeks at a time.

The town has a long way to go – debris still lines some streets, empty storefronts are not filling and many people have not been able to return to Rainelle since their homes were destroyed.

Rainelle founder John Raine’s slogan coined the slogan, “The town built to carry on.” And as the work continues, the slogan still bears truth 111 years after the town start in 1906.

Rainelle community leaders, officials and charitable organizations recount their involvement during the 2016 flood and the long, ongoing road to recovery, the last of a four part series.

“All that they had in the world now, was the clothes on their back. There were kids getting out of rafts and adults too. They were barefoot. They were soaking wet. It was one of the hardest things that I have ever encountered in my life. I mean, probably as bad as losing my dad a few years ago. And I hope that I never ever witness anything like that again.” – Kristi Rader

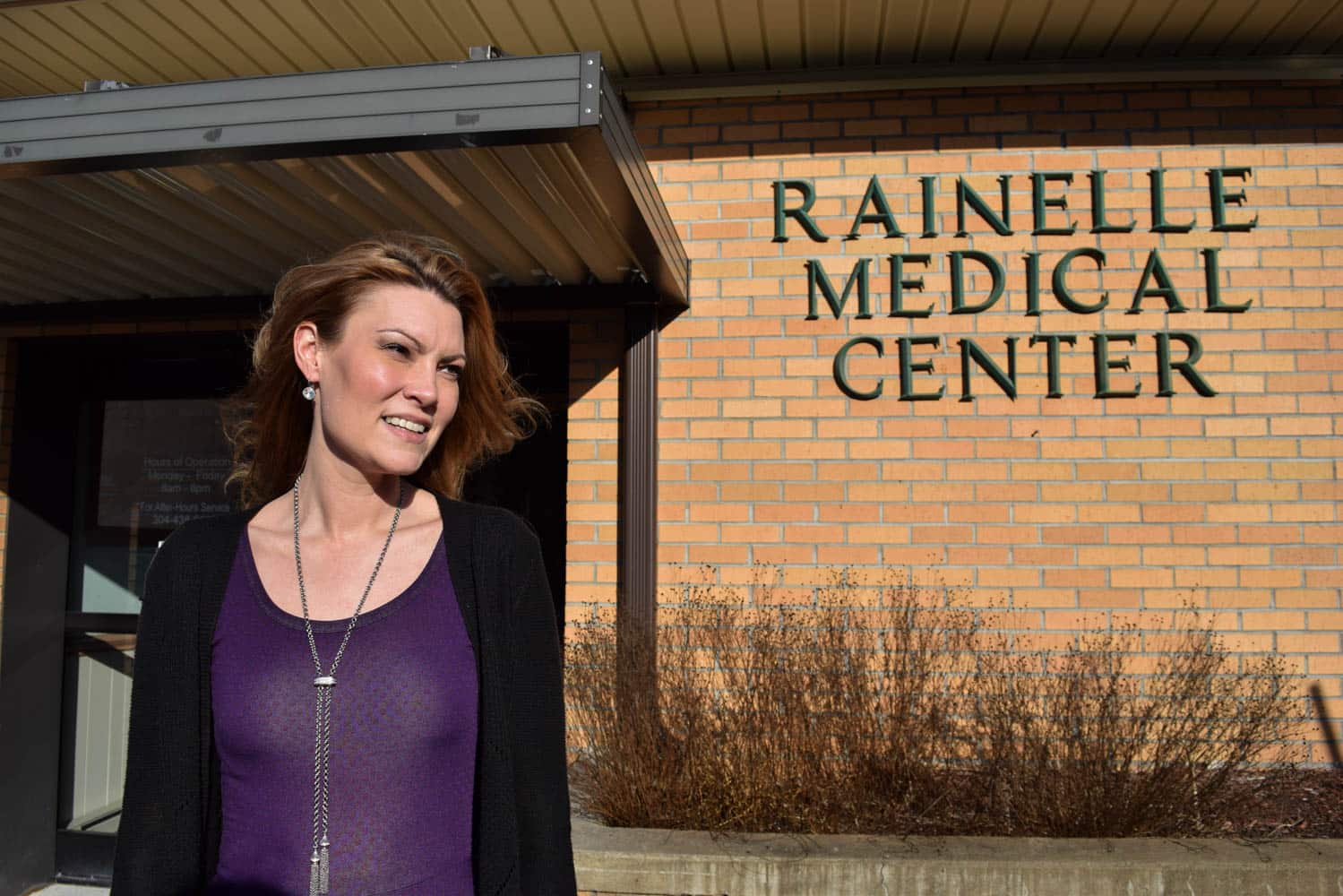

Kristi Rader, chief executive officer of the Rainelle Medical Center, went home to her family in Fayetteville after work on June 23, but her mind was still in Rainelle. She spent all night checking updates on the flood until making her way back down into town around 6 a.m. bringing food and water for first responders and whoever else could use them. She parked at the Hardee’s where most volunteers and rescuers had made base because of its slightly higher elevation.

“The water was dirty. You could smell the oil and the gas and you could see it floating on the top,” Rader recalled.

She watched kids and elderly people load up into rescue rafts out of their homes that had disappeared under the water.

“We started thinking, all these people that have been in this water are going to need vaccinations,” she said. “And we knew that, when the water receded, people who started cleaning up and working on things, they were going to need tetanus shots. So we started checking the supply that we had.”

With help from statewide hospitals, including Charleston’s CAMC Memorial, Marshall University Health, Cabell Huntington Hospital and WVU Healthcare, the Rainelle Medical Center offered thousands of free tetanus and Tdap vaccinations in addition to regular check-ups and basic first aid for those who were hurt during the flood.

“A lot of people didn’t want to leave their homes after the water receded to come get vaccinations so we put together teams of our doctors, our mid-levels and a nurse and then somebody clerical and put them out on Gators,” she explained and we “sent them all over Greenbrier County, parts of Fayette County and parts of Nicholas County to try to make sure that people were vaccinated and and that they were taken care of.”

A few days after the flood waters receded, Rader brought her 8-year-old daughter, Maddy, into Rainelle. They borrowed a friend’s four wheeler to take supplies and food to people around town. Then, they drove up to the ball field. Little League season had just ended for Maddy’s team, but the park in Rainelle was set up for a regional all-star tournament right before the flood hit.

“There were bleachers turned upside down in the middle of the road by the field. The backdrop behind home plate had just caught all the trash,” Rader said. “They had everything set up, and the water had washed it all away.”

As the water drained out of town, so did some of the people. Rainelle Medical Center had between 30 and 40 patients move away. Eleven employees lost homes in the flood, but only one ended up leaving Rainelle.

The medical center continued extended service hours for flood victims and first responders until the weekend of July 4th when regular operation resumed.

The day before the flood hit, Rader signed a lease for a new medical center building in White Sulphur Springs, which received slightly more rain than Rainelle. The building was not affected by the flood. Her company also has a location in Alderson which did not flood. Rainelle Medical Center, located on top of a hill, did not receive any damage, so when Rainelle suffered the brunt of the water impact, Rader and her center were ready.

Looking back Rader said, “I don’t know if all health centers or all of the leadership teams at health centers would have done the things that we did, but I don’t regret one thing, and I know that our board of directors doesn’t either. I would do what we did a thousand times over because I know that it made a difference. It might not have made a difference to a lot of people, but if it helps one person, I’m thankful.”

“Right in this town, there were 150 water shut-offs after the flood. That meant 150 homes that were unlivable just in Rainelle, let alone start adding all across the state.” – Walter Crouch

Walter Crouch’s organization was already embedded in the town of Rainelle when the June 2016 flood destroyed thousands of homes in southern West Virginia. Crouch is the president and CEO of Appalachia Service Project, a nonprofit organization based out of Johnson City, Tennessee, that provides home renovations and new home construction in central Appalachia.

As part of its program New Build Appalachia, which was formed in response to massive flooding in eastern Tennessee in 2012, ASP built a center in Rainelle to serve as a tools and communications hub for southern West Virginia towns where ASP was working. ASP, with the help of 500 volunteers, repaired 20 homes for low-income families in Rainelle in 2015. They were back at it the next summer, all the way up until June 23.

ASP had three work crews of 70 kids and 14 adults out around Greenbrier County that could not safely make it back to the Rainelle center after the flood started.

Crouch was at a convention, exhibiting for ASP, in Greensboro, North Carolina, when crisis hit that day. He started getting reports from centers in other parts of West Virginia – hearing that their power had gone out and their centers were flooding. He traded 87 phone calls, texts and emails with his chief ministry’s officer, Lisa Miller. Parents were calling him because they couldn’t get ahold of their kids on work crews.

Finally, much later that night, Crouch heard from all the groups and everyone was safe. One group had to stay at the client’s home they were working on while the other two were able to make it back to the center. Crouch made it back to Rainelle three days later.

“I felt a connection. I knew we had to do something and whatever we did couldn’t be piecemeal. It would have to be significant enough to where people understood the town was going to do major rebuilding when it came to its housing stock,” he said of his pledge to Mayor Andrea “Andy” Pendleton.

The week after the flood, Crouch pulled resources from ASP work sites and reassigned them to Rainelle. First, ASP had to clean up its own center – muck it out and fix all the showers so volunteers could stay there while serving elsewhere in town.

With the architectural help of Washington County, Tennessee, mayor Dan Eldridge and contractor Ron Gouge, ASP broke ground on the first new construction home in the middle of August.

ASP gives the home to the family with just one restriction: they can’t sell the home for five years after it’s completed. Families are invited to help work on the site, and they are welcome to donate funding, but the recipients are not required to help on the construction of the house.

“We talk about that being kind of a pay it forward situation, where if they’re giving money, we’ll use that money in someone else’s home. But the home that we’re building for them, we see as a grace gift,” Crouch said.

ASP is an ecumenical organization where about 20 different denominations participating. Every year, close to 500 churches serve with ASP on work weeks with college students and other independent groups.

At the start of spring 2017, ASP was looking at building a total of around 70 new homes for flood victims. 49 would be in Rainelle. More than 30 home repairs and major renovations were in the works, too.

“We have this view that God has dealt with us through grace, so we should deal with others through grace,” said Crouch. “If there’s an obligation, it’s no longer grace.”

“Originally the main response were just ragtag groups of churches coming together, saying ‘How can we serve?’ It wasn’t FEMA, it wasn’t Red Cross, it wasn’t any of those things.” – David Bush

On Thursday, David Bush, pastor of First Baptist Church in Rainelle, talked through bad weather plans with his church staff: with all the rain, should Vacation Bible School be canceled for the day?

“Of course we canceled it, but nobody thought it was going to be as bad as it was,” Bush said.

Because the church had ankle-deep water in past flood events, Bush and a church volunteer knew to start moving objects up a few feet off the ground. But the water was rising so quickly, their efforts would not matter. Suddenly Bush heard an “awful slam,” so he ran into one of the Sunday school classrooms, and saw one of the outside doors had blown in, letting water rush into the church building.

“I’ve never felt more helpless than that, ever. There’s no power, you don’t know who’s in their house, who got out, who’s trying to get out,” Bush said. “That night, it was really a helpless moment.”

As the sun set and nearly five feet of water had filled the bottom floor of First Baptist, Bush called one of the former pastors, Dana Gatewood, who pastored there during the town’s last flood.

“I said, ‘What do you do?’ He said, ‘Just try to sleep, because things are about to get really hectic over the next few months,’ ” Bush recalled.

Bush and his wife came to Rainelle in January of 2016, just six months before the flood hit. Their home, just a few blocks away from First Baptist, hardly received any water above their floor.

Friday morning, Bush walked down to the church and waded through waist-deep water to turn off the building’s electric. He had to wait for the water to empty before assessing damage and beginning recovery.

On Saturday, a truck full of church members and supplies from Bush’s hometown church of Oak Hill showed up and started cleaning out the building.

The Christian Life Center, where community dinners and other events were typically held, was cleaned out first so it could be used as a distribution center, lodging place and kitchen for volunteers.

Many churches in downtown Rainelle had extensive water damage. The pastors pulled together by Sunday morning to be able to hold a community service in the Kroger parking lot for members of all churches and the public. The pastors each preached for five minutes to about 100 attendees that Sunday morning.

“Sometimes we have to receive, and sometimes we have to serve one another. It doesn’t matter the name on the top of the door. We just wanted to serve the people and serve the community.” Bush said. “We serve a God who is right there in the middle of this tragedy, who doesn’t stand at the waters in a clean gleaming white robe and say ‘everything will be okay if you just pray.’ He’s right there with you, he’s right in the presence of it.”

Except for their sanctuary, First Baptist’s building was severely damaged by the flood. Eight classrooms, four offices, four bathrooms, a library and an elevator – “it adds up,” Bush said. In-house worship services resumed two Sundays after the flood and it took another few months of replacing carpet, walls and furniture before opening up the rest of the building.

Eighteen families of the church were affected by the flood. Church members Keith Shumaker and Charles Olmechenski, both died during the flood.

“It’s heartbreaking when you hear your family members pass, but when you have a hope that’s beyond this world… Chuck’s hope was not in living the rest of his days in that bed. Chuck’s hope is the fact that he’s regenerated in Christ. Same thing with Keith. I mean, he’s with his wife now, standing on two legs. I just can’t describe the joy that’s in my heart over Keith being in heaven right now,” Bush said.

In the months following the flood, First Baptist Church of Rainelle served as a launch pad for many visiting churches who were in town to repair destroyed homes. They also raised money to organize a voucher system that would attempt to help the individual and the economy, too. With financial donations, First Baptist handed out money vouchers to town residents so they had some extra cash for getting back on their feet. The vouchers could only be used on businesses in town so that those damaged stores could also benefit from some revenue.

Bush reflected on the ordeal, “You can talk about numbers all day and say this how many people came to this, how many people did that, this is how much money was given, how much we give way… But at the end of the day what matters most is that we’re faithful to the mission field that God puts us in. And I think that that’s what we’ve been able to do.”

“It’s been trying on everyone. Emotionally, I think everybody’s trying to hold things together as well as possible. Some of them, their head is still buried in the sand trying to recover everything.” – Jonathan Dierdorff

Jonathan Dierdorff knew it was raining hard while he was in his office, so he checked on the basement fellowship hall because it usually floods.

One minute, there was nothing. Five minutes later, one of the church’s trustees ran up the stairs and told Dierdorff the hall had flooded. He and the remaining people in the building tried to pick up as much as they could from the floor and move it to higher, dry space in the church. The electricity went out and there was nothing more they could do except evacuate.

“I had no idea we were experiencing a flood,” Dierdorff said.

Dierdorff is the pastor for Rainelle United Methodist Church, and he also serves another congregation in nearby Rupert. Some members of that congregation were stranded in Rainelle because the floodwater blocked off Route 60, so Dierdorff and his wife invited them to their parsonage next door to the church building.

With phone lines down and communication off and on for the first few days after the flood, Dierdorff didn’t really know until Sunday who from his congregations were flooded.

With no flood response training, Dierdorff didn’t know how best to serve in the immediate aftermath of the flood. He set up a grill and food station next to the Rainelle Medical Center where people were being taken for treatment after the flood.

“I just made food on the grill because I didn’t know what else to do, and had some prayer with some people who were there. And then really from that point until the end of October, it just felt like sheer chaos every day,” Dierdorff said.

About a foot of mud sat in the fellowship hall, which forced the church to renovate. Dierdorff and his staff took that opportunity to install new facilities for visiting volunteers – new bathrooms, showers and rooms full of cots. Since the flood, Rainelle UMC has hosted volunteer groups, from Americorps to other churches to college students in their building just about every week. He still gets messages from teams asking if they can come help.

“I wish I had kept track of how many groups it was, but it felt like it was a revolving door,” Dierdorff said.

With financial support, Dierdorff’s congregation was able to donate money and appliances bought from local stores to families in need in town. Rainelle UMC also took initiative to fundraise for a specific cause. With $50,000 in donations, the church bought sheetrock from Red Star Auto that they were then able to give away to people rebuilding their homes and businesses in town.

“Word kind of spread through town that you go here and you can get furniture, you go here and you can get this and that, and if you need sheetrock, you can go to the Methodist church in Rainelle.”

For the first five Sundays after the flood, Dierdorff preached about the flood, about anxiety, and about provision. “I knew no one was thinking about anything else,” he said.

But then he knew it was time to talk about something else.

“For weeks, it was very sobering. There were people who had questions of theodicy, ‘Why would God allow something like this to happen?’ ” he said. “But it didn’t take long. Maybe six to eight weeks before we were able to start celebrating what we saw God doing in our community and the fact that we weren’t alone.”

“You hear the ‘bang, bang, bang, bang,’ the song and the sound of the nails, and it’s like music to your ears.” – Andy Pendleton

Andrea “Andy” Pendleton was not planning to run for reelection. She was in the middle of serving her two-year term as mayor of Rainelle. At 70 years old, she figured it was time to retire. She had gone through several surgeries, and her memory was fading.

But when the flood came, she felt a renewed wind at her back.

“My brain was restored. I knew everything and what was going on. I had the energy,” she said.

Pendleton, mayor and lifelong resident of Rainelle, has not slowed down much after a year of flood recovery. She still drives around town every day to see the new home construction or stop by the few open shops on Main Street to check in with their owners.

On those drives and in those conversations, she sometimes finds herself crying. Every empty and rotting plot that used to be a family’s home, every pile of debris still sitting out on side streets, reminds her of all the work left to be done.

It’s hard to say that a different management plan could have prevented some of the damage of a 1,000-year flood, according to Pendleton. Still, many of her nights are spent lying awake and thinking about the flood’s havoc wrecked on her town.

“Sometimes I stand still and don’t know what to do,” she said. “But I keep moving. I feel better when I’m working.”

From working with Appalachia Service Project to get families new homes to communicating with FEMA to get assistance in town, plus deciding what to do with total loss buildings and evaluating the town’s future flood management plans, Pendleton worked every day for the first three months after the flood to get her town rebooted.

“That was my focus, to keep my people here, to keep the community together, to keep the schools flowing,” she said.

And to Pendleton’s joy, the altruism of locals and outsiders alike has helped too.

After a long day of work, Pendleton likes to stop by houses that are being built by charities and church groups. Over 30 new houses were built by Appalachia Service Project within the first nine months after the flood, and other groups like Samaritan’s Purse have helped to repair many more.

Still on the to-do list in Rainelle is dredging the creeks, finding more grant money for reconstructing buildings, maintaining vegetation growth around the creeks, developing the town’s flood plain management plans and clearing more debris with the help of the National Guard.

Though much is left to be done, Rainelle, the town that was built to carry on, has built back up even better than it was before, Pendleton said.

“From day one, I called it our ‘Noah’s Ark.’ I called it a new beginning for our town,” the mayor said.

Pendleton often eats lunch at Fruits of Labor Café, a few buildings down Main Street from City Hall. She greets the other customers, tries all the different menu options and helps put on special events with the restaurant to encourage more residents of Rainelle to support their local businesses.

“Everybody depends on everybody. We need the homes, the people to work for the businesses and the businesses here for the homes,” she said. “It all runs in full circle of everybody helping each other.”

The last day of the sign-up period, Pendleton still wasn’t so sure she wanted to run again, but her friends, neighbors and constituents encouraged her to commit to it one more time.

“Every place I go, they hug me and thank me for running again. And I think that brings peace to me,” she said. “We all should leave our footprints in the sand and say what we’ve done and why we were here on this earth.”

About this series: West Virginia University senior Jennifer Skinner interviewed 19 people in Rainelle, West Virginia to record their stories of the flood from June 23, 2016.