As Congress considers repealing the Affordable Care Act, health professionals in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia grapple with what that might mean for a region where many depend on the law for access to care. This occasional series from the ReSource explores what’s ahead for the Ohio Valley after Obama Care. See more stories here >>

Eight protesters along a major thoroughfare in Lexington hoisted signs shaped like tombstones with sayings such as “RIP Trumpcare.” They were hoping Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin and U.S. Rep. Andy Barr would catch a glimpse of the demonstration on their way to a press event at Valvoline headquarters down the road. Against the steady hum of streaming cars came a few honks. A middle-aged guy on a Harley gunned his bike through the intersection while laying on the horn.

“I don’t know if they are honking for us or if someone actually got in their way,” said Peter Wedlund, who is wearing a black Grim Reaper cloak.

Even in the very red Ohio Valley region a growing number of people are protesting the American Health Care Act, which would repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare.

Some protesters who have long been in the trenches on the health care fight said they are newly motivated by some startling findings recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association’s publication JAMA Internal Medicine.

That research grabbed headlines for its conclusions that in some parts of Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia people can now expect to live shorter lives than their parents did. This goes against the widespread trend of longer lives, and the grim mortality statistics put the stakes of the health debate in stark relief.

A Health Divide

Wedlund had concerns about healthcare in Kentucky before. The JAMA statistics just confirmed his worst suspicions about how “Trumpcare” might play out in the region.

“The life span is going down. It is actually worst in Hal Rogers’ 5th District,” he said. Rogers’ district covers eastern and southeastern Kentucky.

Folks like Wedlund who’ve been following health policy knew instinctively what the statistics published by JAMA spotlight. Together, Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia lay claim to 27 of the 50 counties with the country’s worst trends in life spans. Of the 10 counties in the U.S. with the worst declines in life expectancy, eight are in Kentucky.

Rep. Barr’s 6th District includes two of those counties, Powell and Estill. Rep. Rogers’ district includes six of those counties – Breathit, Clay, Lee, Leslie, Owsley, and Powell. Owsley County leads the list with the worst change in life expectancy in the United States over the 35 years of data the JAMA study covered.

Wedlund and the others who staked out the corner of Blazer Parkway and Man o’ War Boulevard belong to Indivisible Bluegrass, which organized the protest via social media.

The national Indivisible group, according to its website, claims at least two grassroot groups in every congressional district and aims to “resist Trump’s agenda.”

Near Wedlund sat Susan Fister, who ran the Bluegrass Community Health Center in Lexington for decades. Its two clinics serve mostly poor people on Medicaid. Retired now, she’s worried that if approved the AHCA would require one of the clinics to close. The number of patients served and the number of employees would be cut in half.

She sat on a hot sidewalk with a sturdy black cane hanging over the arm of the kind of folding chair parents take to soccer games. A chronic illness makes moving difficult. She read from a sign propped in her lap.

“Valvoline provides jobs; Barr and Bevin provide misery. Stop the AHCA,” she said.

Protests like these have popped up around the region for months as Congress debated and voted on repealing the ACA. Indivisible Bluegrass has been trying to track Barr, who represents Lexington and surrounding counties, at every public stop he makes in the district in May. About 100 people turned out to rally outside a private dinner Barr attended on the University of Kentucky campus.

The demonstrators see a disconnect between the region’s dire health statistics and the health care votes cast by their representatives in Congress. Of the 25 House members representing the Ohio Valley region, 17 voted for AHCA.

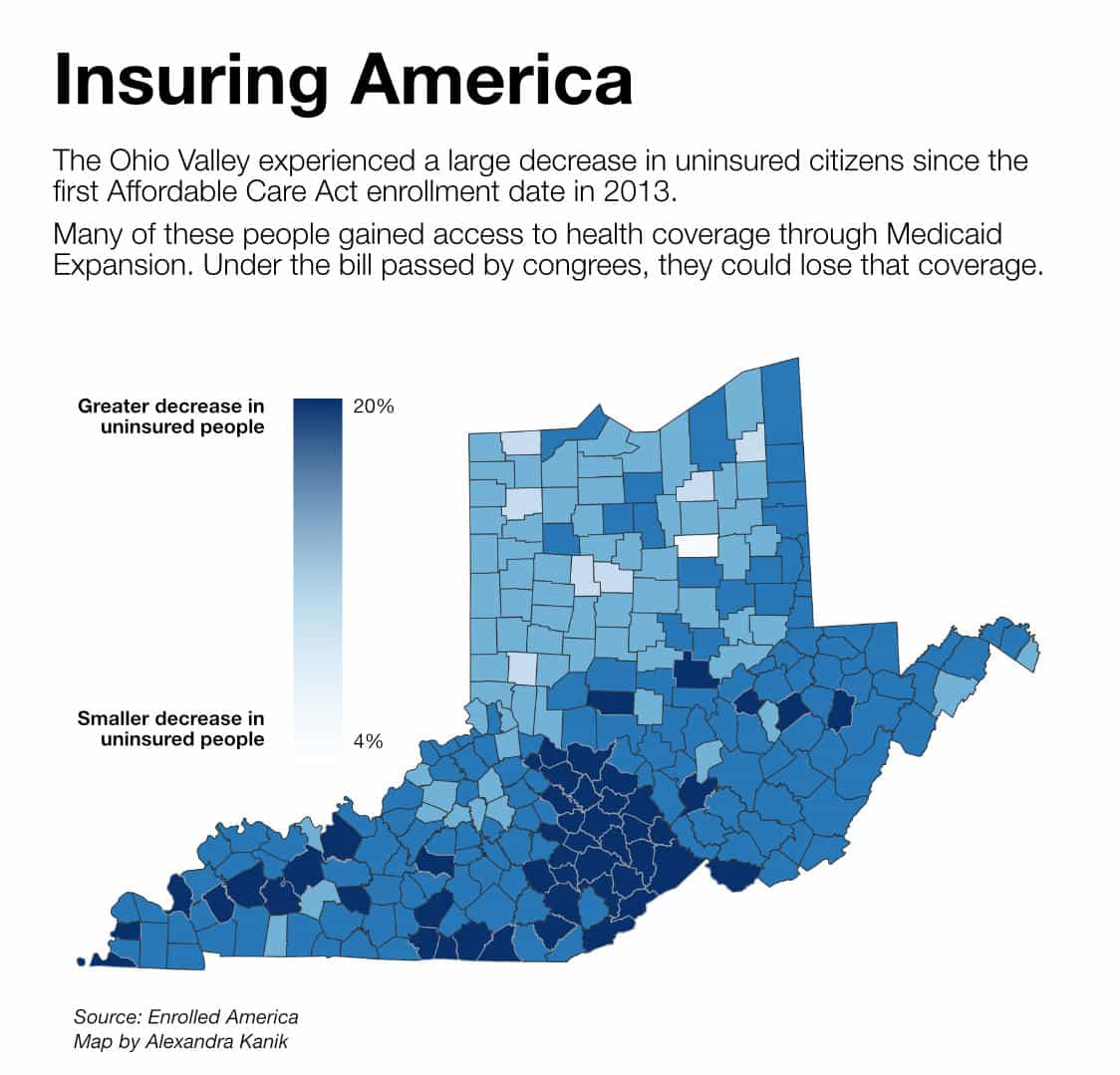

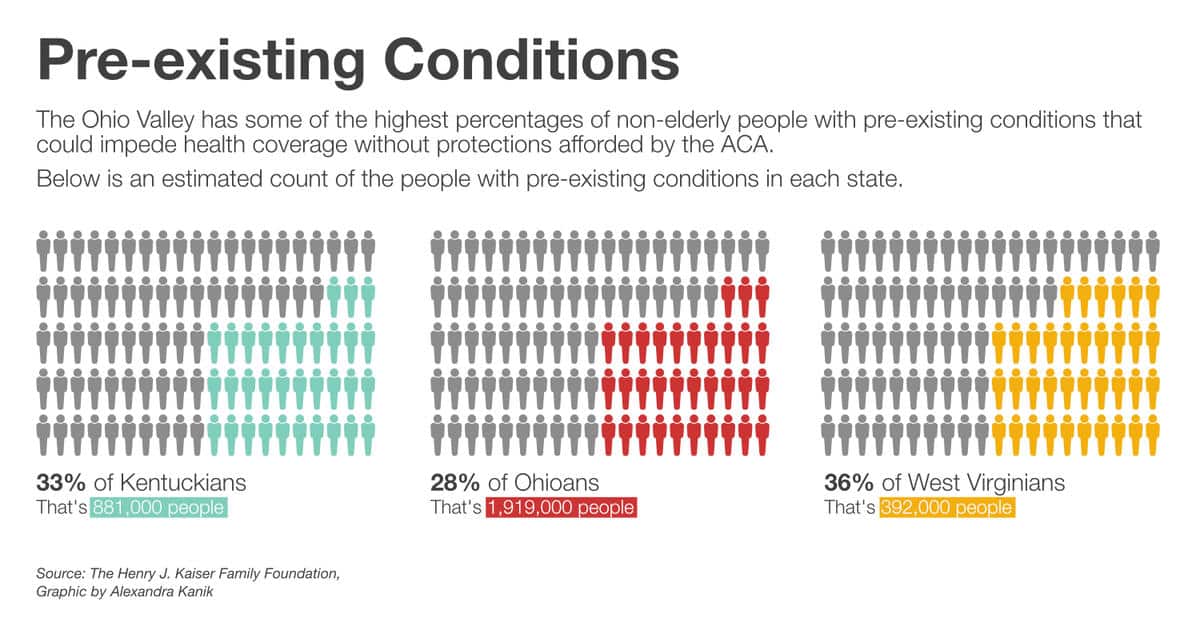

Opponents fear the bill will reduce health care access for the sickest and poorest in a region that benefited greatly from the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, and where high percentages of people have pre-existing health conditions.

Barr spokesman Rick VanMeter said that the congressman continues to support the health care bill. Barr explained his position in an interview with WEKU Content Director John Hingsbergen in early May.

“This is what the people of central Kentucky said, that they wanted us to repeal Obamacare. We’ve kept that promise,” Barr said. He called the day of the vote “a good day for the American people who are facing higher costs and fewer choices in their healthcare.”

Tough Choices

Hours after Fister and Indivisible took to the sidewalk, a political action committee called the People’s Campaign set up in a hotel conference room across town. Minister L. Clark Williams of Shiloh Baptist Church said the campaign hopes to encourage candidates to run against incumbents and oppose the AHCA. They also are expressly looking for a candidate to challenge Barr. Williams said they are creating a network that includes Louisville and several counties in western Kentucky as well.

One of the speakers was Cara Stewart, a health policy lawyer and longtime advocate. She helped sign up thousands of people for Medicaid in Kentucky, something made possible under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Lately, she said, she’s felt physically ill from thinking about what will happen to the folks she promised would have health insurance.

She said some of the more dramatic aspects of the AHCA, such as the possibility that pregnancy would be considered a pre-existing condition, are even hard for her to take in.

“Even when I hear myself talking, it seems so hyperbolic,” she said.

She said she sees grassroots protest efforts picking up momentum. She recently hosted an event where people filled out postcards to send to legislators decrying the AHCA. With just one day’s notice, 20 people showed up.

“We used all the postcards I had,” she said. Plus, someone brought money for stamps. “So that gives me hope.”

But as the bill moves to the Senate, she said, she fears many people might tune out from the health debate because it is so complicated and divisive.

“It’s so terrible that people do think it is dead on arrival,” in the Senate, she said. She thinks many are assuming that “there are too many reasonable people” for such a bill to pass. “But then, it passed the House,” she said.

Personal Experience

Rev. Williams asked Colmon Elridge to come to the podium to share his story. Elridge worked closely with former Gov. Steve Beshear to expand Medicaid in Kentucky.

He is worried about what might happen in particularly poor areas, such as the 5th District, where analyses of the AHCA estimate 70,000 people could lose Medicaid. But Elridge also said the diseases most affecting people disregard borders. As the JAMA statistics show, he said, health care is a regional concern.

According to the Washington-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities the AHCA would remove insurance from the 76,000 rural West Virginians who gained health coverage through Medicad expansion.

Policy Matters Ohio, a non-profit research institute, estimates that 700,000 people in the state will lose coverage if the Medicaid expansion is rolled back.

Elridge said he hopes voters understand the seriousness of the situation and how important it is to fight back. They elected people who promised to repeal Obamacare and it’s happening.

“Now that they know that these people are true to their word, we have to be true to our cause,” he said. Otherwise, he warned, “we are going to be to a place very quickly where people will die.”

The AHCA as passed by the House addresses pre-existing conditions by creating what are called “high risk pools.” Health policy advocates say those pools have historically not been effective and that the current bill does not contain enough funding to provide adequate coverage.

The People’s Campaign event didn’t draw many people. The small crowd kept to the back rows. Williams wasn’t concerned. He said the intended audience is via Facebook Live. A tech guy squinted at his phone searching for bars as Elridge took the podium.

The story Elridge told shows the personal struggles behind the region’s mortality statistics.

At age 3, his father killed himself, a result of untreated mental illness. At age 14, Elridge recalled, his mother took to her bed for several days. The family first prayed, as they always did when anyone was sick, because they couldn’t afford a doctor. Then Elridge called the town veterinarian, the only doctor he knew. The vet told Elridge his mother had to go to the hospital.

She said no. They didn’t have the money. Finally, in defiance of his mother Elridge called an ambulance.

His mom survived.

After his speech, sitting in the hotel lounge, Elrdige said the idea that he could have lost his mother still affects him. What if he had made a different decision?

“I’m trying not to cry,” he said, not succeeding very well. After losing his father, he said, “I could not fathom losing another one. She had pneumonia. If I had just said ‘you’re right, Mom. I won’t call,’ and I buried my mother because of pneumonia?” he shakes his head in disbelief of that possibility.

He said he is fighting the AHCA because he doesn’t want anybody else to have to make a choice like that.

This story was originally produced by Ohio Valley ReSource.