The alternate route would run down the wooded hillside, bisecting the scenic meadows and hayfields. It would pass the small barn and quaint home within several hundred feet, and cut a path through the grave site of a cat named Tessa and a beloved hound dog named Elvis.

That’s the fear Bryan and Doris McCurdy have harbored since the Monroe County couple first found out a 42-inch gas pipeline might be laid through the piece of property they have called home since the 1980s. The steel pipe, capable of carrying 2 billion cubic feet of gas per day, would be buried just above their house and freshwater spring.

After being notified surveyors wanted to plot a route past their secluded home, the couple unexpectedly found themselves consulting with attorneys, addressing their county commissioners and traveling from one courthouse to another in an attempt to make sure the Mountain Valley Pipeline didn’t become a permanent fixture in their backyard.

In doing so, the couple have been thrust into the center of a precedent-setting lawsuit over whether EQT, the pipeline developer, and other corporations can use eminent domain to survey the property of unwilling landowners in West Virginia.

Less than a week after the 2016 election, the West Virginia Supreme Court issued a ruling in the McCurdys’ favor, arguing EQT and other gas transmission companies planning billions of dollars worth of interstate pipelines out of West Virginia cannot survey land without a property owner’s permission.

The opinion was welcomed by property rights groups and environmental advocates, but it was seen as a legal setback for the gas companies, which have become powerful players in West Virginia politics of late. Those gas companies lobbied the West Virginia Legislature last year to change state law before the Supreme Court could rule on the eminent domain issue.

That industry-backed legislation was ultimately defeated in the state Senate, but rumors of possible efforts to resurrect the bill and overturn the McCurdys’ favorable ruling through legislative fiat have already begun to circulate at the state Capitol this year.

Natalie Cox, a spokeswoman for EQT, said the company will make a decision in the coming days as to whether it will ask state lawmakers to overturn the legal ruling. But she said the court opinion isn’t expected to delay the $3.5 billion project in the meantime.

In many ways, last year’s debate in the Legislature was cast as a choice between protecting the property rights of West Virginians or conforming to gas industry requests in the hope it will improve a portion of the state’s lagging economy.

The suggestion that state lawmakers might seek to overturn everything the McCurdys and their attorneys with Appalachian Mountain Advocates have fought for in the past two years leaves Bryan McCurdy exasperated. The former utility employee said most of his thoughts on that possibility aren’t fit for print.

“If our Legislature changes the law, they, as far as I’m concerned, are making a statement to the world that the profit that private companies make and what incidental money happens to come to people in this state is more important than the rights and interests of the citizens,” he said, as he sat in his living room on a recent rainy afternoon.

The McCurdys’ fight over the pipeline survey highlights a new era of energy development in the Mountain State, as natural gas production in the northern counties has surged and the coal industry in Southern West Virginia continues its historical decline.

Cox said the Mountain Valley Pipeline is primarily needed to fuel the increasing number of gas-fired turbines out-competing the country’s aging coal-fired power plants.

Many lawmakers and business officials in West Virginia have been quick to support expansion of the growing industry, especially at a time when the state is facing increased unemployment and a budget shortfall currently estimated at half a billion dollars in the next fiscal year.

Many lawmakers and business officials in West Virginia have been quick to support expansion of the growing industry, especially at a time when the state is facing increased unemployment and a budget shortfall currently estimated at half a billion dollars in the next fiscal year.

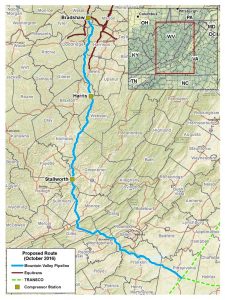

The half dozen new interstate pipelines being planned in West Virginia, industry representatives say, are needed to increase the flow of natural gas to markets in states like Michigan, Louisiana and North Carolina.

EQT and the other pipeline developers that have requested federal approval to lay thousands of miles of steel under streams, over hilltops, through national forests and around people’s homes have emphasized the jobs and tax revenue the large pipelines would provide.

Those projects include the Rover, Leach Xpress, Mountaineer Xpress and Atlantic Coast pipelines. Industry officials hope those lines will lead to increased production in the Marcellus Shale region of the state.

Combined, the new pipelines will be capable of carrying more gas per day than the entire state of West Virginia is currently producing, which has caused groups to question whether all of the lines are needed.

The projects, however, could get a boost from President Donald Trump’s new administration, which has already shown an interest in pushing large pipeline projects throughout the country.

Earlier this week, Trump signed executive orders that could advance the delayed Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines that have been at the center of national protests. A planning document obtained by national news organizations also lists the Atlantic Coast pipeline as one of the Trump transition team’s top infrastructure priorities.

But for homeowners and residents in areas like Monroe County, which has been left relatively untouched by the state’s coal industry, the possibility of a large-diameter pipeline being constructed in their community is unsettling.

Organized protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline have grabbed the nation’s attention, but the battle over pipelines and property rights in places like Monroe County have gone on relatively unnoticed.

The McCurdys and many of their neighbors are opposed to the Mountain Valley Pipeline altogether. They question the need for the half dozen new gas lines in the region — several of which have similar destinations to the southeast — and they are suspect of the number of jobs EQT and other pipeline builders say the projects will create.

They don’t want this new wave of energy development to leave their home county the way surface mining operations have left a large portion of Southern West Virginia with irreparable changes to the mountainous landscape.

“It’s going to be a repeat of the coal industry at the turn of the century,” Bryan McCurdy said. “It’ll be a repeat of mountaintop removal. It’s just another chapter in the rape of West Virginia. I mean, plain and simple.”

It would be one thing to build a 42-inch pipeline through the Kanawha Valley, where there is a history of development and chemical manufacturing, Bryan McCurdy said. But it’s another thing to build that type of pipeline through the cattle farms and corn fields of Monroe County, he said.

The McCurdys’ lawsuit showed the gas being pumped through the Mountain Valley Pipeline wasn’t currently expected to be used by residents in West Virginia. It’s bound for Virginia, where it will be pumped into another large gas line that serves parts of the East Coast.

Not everyone in the region is vehemently opposed to the pipelines. Some people, Bryan McCurdy said, support the project and hope it might provide economic stimulus to the rural county, which had about 13,500 residents in 2015.

They’re for any and every type of development, he said.

The dispute over the Mountain Valley Pipeline, however, is not the first time Monroe County residents have come out in opposition of a major utility project. In the 1990s, they successfully resisted a high-voltage power line that would have run through the county.

That local organization has started anew. County residents have formed an opposition group to resist the pipeline, called Preserve Monroe, being reviewed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Signs protesting the pipeline can be seen all along U.S. 219, a winding highway, dotted with old barns and small antique shops, which runs the length of the county. One of the McCurdys’ neighbors has even painted the rusting metal roof of an abandoned home next to the roadway in protest.

“Tell M.V.P No Frackn Pipeline!!!” it reads. It’s painted over the faded lettering of a similar message against the high-voltage power line that had been proposed more than two decades earlier.

Several people in the community have asked Doris McCurdy why she and her husband continue to put up such a fight. They think the pipeline is coming through no matter what, even if EQT can’t force the McCurdys and other landowners to allow surveyors onto their property.

“If it does, it does,” she’s told those people. “But they will know we’re here, and they will know we do have a voice in things.”

The McCurdys didn’t want to be at the center of a major state Supreme Court case or at the center of an ongoing political debate over the role of the natural gas industry in West Virginia.

They just wanted to be left alone to enjoy the home they paid off after a lifetime of work. They don’t want to have their property, which has an unobstructed view of Peters Mountain just across the border in Virginia, altered by a gas pipeline.

Bryan McCurdy, who was a geotechnical technician at the Bath County hydroelectric station in Virginia, has been working in recent years to develop better habitats on his land for wild turkeys and monarch butterflies.

He has a 200-yard shooting range on another piece of his property, where he is working with a neighbor to improve the fields for hay production.

All of that work could be ruined, he said, if FERC decides the alternate route running through his land is the best option for the proposed pipeline.

Doris McCurdy is a retired Monroe County librarian who enjoys yoga classes in the nearby town of Union. She helped organize the Monroe County Quilt Trail that constructed the colorful patterns on barns throughout the county. Her own hand-painted quilt square, named “The Farmer’s Daughter,” hangs on the side of the couple’s barn, within feet of the proposed pipeline right-of-way.

She’s still unsure whether she would want to live next to the gas line if it is approved.

“I’m a Monroe County native, and I love it here,” she said. “The question is, where would I go?”

She’s hoping she won’t have to answer that question.

This piece was originally published by The Charleston Gazette-Mail.