It was the sort of white flight that could never have identified itself as such: My family was pulled as much as pushed from Gwinnett County to Forsyth. Only a little farther from Atlanta, the schools shrank by an order of magnitude. It was less than an hour away, but the traffic choked less. To my 12-year-old self, it seemed merely circumstantial that in the course of the move to a traditionally rural area, the entire Black population also disappeared.

In my family’s pursuit of the American Dream, Cumming — county seat of Forsyth — became my home base from 2002 until now. My brother and I thrived in those smaller schools. We swam in Lake Lanier and climbed Sawnee Mountain and played trivia over root beer and pretzels at the Mellow Mushroom back when it was still dingy. We still complained about Forsyth because that’s what teenagers do, but mostly we loved it.

After college I came to recognize how thoroughly privileged my seemingly normal adolescence was; the after-school activities, the safe but laid-back school environment, the leafy neighborhood, the ‘95 Buick my folks paid for until I totaled it. Still, though I theoretically understood these things had been systematically denied to most Black people over the last 400 years, I didn’t learn until 2016 that Black people had been forcibly erased from my hometown. It was only with the publication of Patrick Phillips’ historical account Blood at the Root that the whole truth was told: Forsyth had expelled all its Black citizens through a campaign of terror that lasted from 1912 until after my own birth.

The beginning of the story is disturbingly common. A white woman was raped and murdered. Two young Black men, Ernest Knox and Rob Edwards, took the blame without evidence. Knox was lynched while in police custody, and Edwards was hanged after a sham trial.

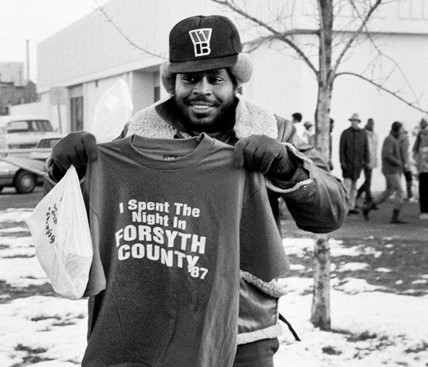

But the county’s white citizens weren’t appeased. Over the course of several weeks, groups of night riders expelled every Black family from Forsyth with threats, violence and fire. Black churches burned. Law enforcement took no interest. Feeble efforts by whites to stop the campaign were quashed. Practically overnight, Forsyth became a whites-only county — one quick to discover transgressors, who would be met with continued violence for much of the century. In 1989, a civil rights march demanding the county work to protect Blacks and speed integration met with an enormous and impassioned counter-protest.

Meanwhile, the land Black families had owned before the 1912 expulsion was slowly absorbed into the holdings of their white neighbors. Now some of the most valuable real estate in the Atlanta suburbs is twice-stolen: first in the Cherokee removal, and again in the 1912 attacks.

When my family moved to Forsyth, this history was known to Black people all over the state; but within the county, this is all taboo. Like other classrooms full of white children all over the country, we learned about slavery, lynchings, and racism in the abstract—but never heard mention of the brutal pageant that had taken place blocks from where we sat. Over 400 students (seven of whom were Black) would eventually graduate from Forsyth Central High School in 2008 at the dusty fairgrounds—filing in and out of the empty livestock barn—having heard only the barest rumors explaining the racial makeup of our hometown.

Since then, the county has continued to grow by more than 25 percent, while the Black population has doubled. One newcomer is Daniel Blackman, community organizer and COO of communications firm Social Karma, who moved to Forsyth from Atlanta with his family in 2012. In 2016, Blackman became the first Black person to run for office in Forsyth and the first Democrat to run for State House in 25 years. Blood at the Root was published months before the election. Blackman says he had heard about the county’s history but didn’t realize the full story until the publication of the book. At the same time, in its current state, Forsyth is “not too different from other predominantly white counties in Georgia” where racism is an everyday occurrence.

Overall, though, Forsyth is better known today for McMansions than for racist conspiracies.

Now, “Forsyth likes who we are,” says Rev. Keith Oglesby of Cumming’s Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit. “[People wonder] why go backwards? But [I still want to ask], who are we? How do we own who we are today?”

Oglesby belongs to a small group of people in the beginning stages of advocating for a memorial to the events of 1912. The group, which coalesced after a lecture in Cumming by Patrick Phillips, seeks acknowledgment of the past in a public place, agreeing that the memorial should be “effective but not adversarial” in order to bring healing to Forsyth. They have also sought to have Blood at the Root placed on reading lists for public school students in the county.

Opposition to a memorial is as inevitable as more clear-cutting for more housing. Members of some of the county’s oldest families still hold positions in local government; newcomers will ask why we should continue to bear shame for others’ past actions. But a memorial is not about shame or even blame, and we cannot take full responsibility for the present without one.

A memorial is not about shame or even blame; and we cannot take full responsibility for the present without one.

Without a memorial, we function like a family in denial. I learned about Forsyth’s history of racial terror by accident, on the radio, from NPR’s Terry Gross, exactly like learning a sick secret about a relative from a far-flung family acquaintance. Meanwhile, the events of 1912 fester and their consequences continue to metastasize, shame and secrecy compounding the slow poison of that all-too-comfortable, subtle racism pervasive in personal attitudes and public systems alike. Meanwhile, students leave our schools ill-informed and ill-equipped to function in a globalized world.

I have had the privilege of studying history, while the oppressed have borne the burden of remembering it. A memorial at its best would invite us to a sacred place to finally remember alongside one another, a communal site for grief and for exploring how the past lives on in us. White people might not be able to agree on the magnitude of our debt, but we could acknowledge it exists. We could be allowed to reckon with injustice as a community, instead of wondering or ranting about it from behind our screens.

Even if the memorial never became those things, it would fulfill its most obvious and important function — to tell the truth. Supporters and opponents alike might suddenly find themselves freed by it—delivered from secret-keeping. But as long as fear and shame control us, invisible gag orders fully in effect, we acquiesce to our own haunting, and the past will never lie peacefully in the past.

Lyndsey Medford is a youth pastor and writer on social justice, Christianity, embodiment, and place. She lives in Charleston, South Carolina where she snuggles with her husband and rescue dog. Her writing is found at lyndseymedford.com as well as Amity Coalition, Fathom Magazine, and The Billfold.